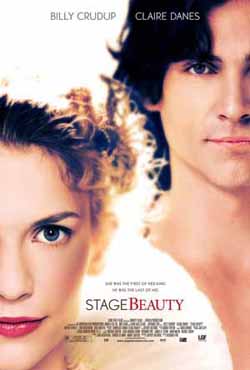

Critical reception

On review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an approval rating of 64% based on 128 reviews, with a weighted average of 6.5/10. The site's critical consensus reads: "Uneven but enjoyable, Stage Beauty uses historical events as the springboard for a well-acted romance with a charming Shakespearean spin." [4] On Metacritic, the film has a weighted average score of 64 out of 100, based on 38 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews". [5]

In his review in The New York Times , A. O. Scott said, "At times, the movie feels like a fancy-dress version of A Star Is Born ... Mr. Crudup's fine features, which flicker between masculine and feminine as the lighting changes and the mood shifts, are well suited for the role, though his sinewy, birdlike frame suggests Hollywood anorexia more than Restoration curviness ... Stage Beauty is both timorous and ungainly, words that might also describe Ms. Danes's performance. Trapped in an English accent and in a character who must appear conniving and warmhearted in turn, she veers from teariness to brisk indignation like an Emma Thompson doll with a jammed switch. The British actors in smaller roles handle the material better ... George Fenton's Sunday-brunch score, on the other hand, is an indigestible dose of good taste ladled heavily over even the film's witty and delicate moments." [6]

David Rooney of Variety called the film "an intelligent and entertaining adaptation ... skillfully acted, handsomely crafted" and added, "Eyre's spry direction of the refreshingly literate, witty drama shows a pleasingly light touch and a genuine feel for the bustle, backbiting and rivalry of the theater milieu ... In a delicately measured performance that favors graceful subtlety over campy mannerism, Crudup conveys a nuanced sense of a man struggling to know himself ... Put in the unenviable position of playing second fiddle to her male co-star in terms of feminine allure, Danes is lovely nonetheless ... George Fenton's rich orchestral score enlivens the action with an occasional rousing Celtic flavor." [7]

In Rolling Stone , Peter Travers rated the film three out of a possible four stars and called it "bawdy fun ... the gender role-playing puts spine in this period piece that is vital to the here and now." [8]

Carla Meyer of the San Francisco Chronicle said, "The film rarely matches Crudup's performance, appearing confused itself about whether it's farce or drama. But its palette of burnished browns and reds pleases the eye, and at its best, Stage Beauty captures the tensions and electricity of backstage dramas." [9]

In The New Yorker , David Denby observed, "Second-rate bawdiness—that is, bawdiness without the wit of Boccaccio or Shakespeare or even Tom Stoppard—is more infantile than funny, and I'm not sure that the American playwright Jeffrey Hatcher, who concocted this piece for the stage and then adapted it into a movie, is even second-rate. Stage Beauty might be called the spawn of Shakespeare in Love , and, unfortunately, this is a Shakespeare that lacks the graceful spirit and breathless narrative drive of its progenitor." [10]

Owen Gleiberman of Entertainment Weekly rated the film C+ and described it as "an odd amalgam of high spirits, lively ambition, and botched execution." [11]