The United States produced 5.2 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in 2020, the second largest in the world after greenhouse gas emissions by China and among the countries with the highest greenhouse gas emissions per person. In 2019 China is estimated to have emitted 27% of world GHG, followed by the United States with 11%, then India with 6.6%. In total the United States has emitted a quarter of world GHG, more than any other country. Annual emissions are over 15 tons per person and, amongst the top eight emitters, is the highest country by greenhouse gas emissions per person. However, the IEA estimates that the richest decile in the US emits over 55 tonnes of CO2 per capita each year. Because coal-fired power stations are gradually shutting down, in the 2010s emissions from electricity generation fell to second place behind transportation which is now the largest single source. In 2020, 27% of the GHG emissions of the United States were from transportation, 25% from electricity, 24% from industry, 13% from commercial and residential buildings and 11% from agriculture. In 2021, the electric power sector was the second largest source of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions, accounting for 25% of the U.S. total. These greenhouse gas emissions are contributing to climate change in the United States, as well as worldwide.

The Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate Policy is the Netherlands' ministry responsible for international trade, commercial, industrial, investment, technology, energy, nuclear, renewable energy, environmental, climate change, natural resource, mining, space policy, as well as tourism.

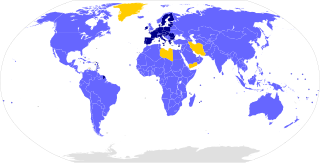

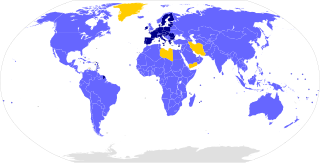

The Paris Agreement, often referred to as the Paris Accords or the Paris Climate Accords, is an international treaty on climate change. Adopted in 2015, the agreement covers climate change mitigation, adaptation, and finance. The Paris Agreement was negotiated by 196 parties at the 2015 United Nations Climate Change Conference near Paris, France. As of February 2023, 195 members of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) are parties to the agreement. Of the three UNFCCC member states which have not ratified the agreement, the only major emitter is Iran. The United States withdrew from the agreement in 2020, but rejoined in 2021.

The total electricity consumption of the Netherlands in 2021 was 117 terawatt-hours (TWh). The consumption grew from 7 TWh in 1950 by an average of 4.5% per year. In 2021, fossil fuels, such as natural gas and coal, accounted for about 62% of the total electricity produced. Renewable energy sources, such as biomass, wind power, and solar power, produce 38% of the total electricity. One nuclear plant in the Netherlands, in Borssele, is responsible for about 3% of total generation. The majority of the electricity, more than 75%, is produced centrally by thermal and nuclear units.

Climate change has resulted in an increase in temperature of 2.3 °C (2022) in Europe compared to pre-industrial levels. Europe is the fastest warming continent in the world. Europe's climate is getting warmer due to anthropogenic activity. According to international climate experts, global temperature rise should not exceed 2 °C to prevent the most dangerous consequences of climate change; without reduction in greenhouse gas emissions, this could happen before 2050. Climate change has implications for all regions of Europe, with the extent and nature of impacts varying across the continent.

The Clean Power Plan was an Obama administration policy aimed at combating anthropogenic climate change that was first proposed by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in June 2014. The final version of the plan was unveiled by President Barack Obama on August 3, 2015. Each state was assigned an individual goal for reducing carbon emissions, which could be accomplished how they saw fit, but with the possibility of the EPA stepping in if the state refused to submit a plan. If every state met its target, the plan was projected to reduce carbon emissions from electricity generation 32% by 2030, relative to 2005 levels, as well as achieving various health benefits due to reduced air pollution.

Climate change is leading to long-term impacts on agriculture in Germany, more intense heatwaves and coldwaves, flash and coastal flooding, and reduced water availability. Debates over how to address these long-term challenges caused by climate change have also sparked changes in the energy sector and in mitigation strategies. Germany's energiewende has been a significant political issue in German politics that has made coalition talks difficult for Angela Merkel's CDU.

Climate change litigation, also known as climate litigation, is an emerging body of environmental law using legal practice to set case law precedent to further climate change mitigation efforts from public institutions, such as governments and companies. In the face of slow climate change politics delaying climate change mitigation, activists and lawyers have increased efforts to use national and international judiciary systems to advance the effort. Climate litigation typically engages in one of five types of legal claims: Constitutional law, administrative law, private law (challenging corporations or other organizations for negligence, nuisance, etc., fraud or consumer protection, or human rights.

Urgenda is a nonprofit foundation (stichting) in the Netherlands which aims to help enforce national, European and international environment treaties. In 2013, Urgenda filed a lawsuit against the state of the Netherlands – respectively also against the government – at the court of The Hague, to force them to make more effective policies that reduce the amount of emissions, with the aim to protect the people of the Netherlands against the effects of climate change and pollution.

The Netherlands is already affected by climate change. The average temperature in the Netherlands rose by more than 2 °C from 1901 to 2020. Climate change has resulted in increased frequency of droughts and heatwaves. Because significant portions of the Netherlands have been reclaimed from the sea or otherwise are very near sea level, the Netherlands is very vulnerable to sea level rise.

Friends of the Irish Environment v Government of Ireland was an important climate change case decided by the Irish Supreme Court in 2020. In the case, the Supreme Court quashed the Government of Ireland's 2017 National Mitigation Plan on the grounds that it lacked the specificity required by the Irish Climate Action and Low Carbon Development Act 2015. The Supreme Court ordered the government to create a new plan which was compliant with the 2015 Climate Act.

Tessa Khan is an environmental lawyer who lives in the United Kingdom. She co-founded and is co-director of the Climate Litigation Network, which supports legal cases related to climate change mitigation and climate justice.

Milieudefensie v Royal Dutch Shell (2021) is a human rights law and tort law case heard by the district court of The Hague in the Netherlands in 2021 related to efforts by several NGO's to curtail carbon dioxide emissions by multinational corporations. It was brought by the Dutch branch of Friends of the Earth and a group of other NGO's against the oil corporation, Shell plc. In May 2021, the court ordered Shell to reduce its global carbon emissions from its 2019 levels by 45% by 2030, relating not only to the emissions from its operations, but also those from the products it sells. It is considered to be the first major climate change litigation ruling against a corporation.

West Virginia v. Environmental Protection Agency, 597 U.S. 697 (2022), is a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court relating to the Clean Air Act, and the extent to which the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) can regulate carbon dioxide emissions related to climate change.

The Oslo Principles, formally the Oslo Principles on Global Obligations to Reduce Climate Change, are a set of principles identifying the legal obligations of states to limit climate change, as well as means of meeting these obligations. Written by an international group of legal experts, the Principles’ goal is to limit the rise in average global temperature to 2 degrees Celsius. The Oslo Principles were presented on March 30 at King’s College London.

Lliuya v RWE AG (2015) Case No. 2 O 285/15 is a German tort law and climate litigation case, concerning liability for climate damage in Peru from a melting glacier, against Germany's largest coal burning power company, RWE, which has caused approximately 0.47% of all historic greenhouse gas emissions. It is currently on appeal in the Upper State Court, Oberlandesgericht Hamm.

Neubauer v Germany 1 BvR 2656/18 is a landmark German constitutional law case, concerning the duty of the German federal government to take action to prevent climate damage.

Smith v Fonterra Co-Operative Group Ltd [2024] NZSC 5 is a landmark New Zealand tort law case, concerning liability of major fossil fuel polluters for climate damage. The NZ Supreme Court held that polluting companies could be liable in tort to pay damages from global warming and rising sea levels to people whose coastal property is damaged, overturning courts below.

Greenpeace v. Eni is a 2024 human rights law and tort law suit heard by the Civil Court of Rome, Italy related to efforts by several NGOs to reduce carbon dioxide emissions by multinational corporations. The lawsuit was brought by the Italian branch of Greenpeace, the advocacy group ReCommon, and twelve civil plaintiffs. The suit was filed against energy company Eni and two of its co-owners, the Italian Ministry of Economy and Finance and the investment bank Cassa Depositi e Prestiti.

Verein KlimaSeniorinnen Schweiz v. Switzerland (2024) was a landmark European Court of Human Rights case in which the court ruled that Switzerland violated the European Convention on Human Rights by failing to adequately address climate change. It is the first climate change litigation in which an international court has ruled that state inaction violates human rights.