Stench compounds are chemicals, almost always organic chemicals, that have an unpleasant odor. Their odor contrasts with that of fragrance compounds.

Stench compounds are chemicals, almost always organic chemicals, that have an unpleasant odor. Their odor contrasts with that of fragrance compounds.

A stench can only be detected if the compound exhibits some volatility. As for fragrance compounds, volatility typically requires a molecular weight < 300.

An important factor relevant to stench is the odor detection threshold. Odors of compounds can also vary with concentration. Civetone, produced by civets, has a strong musky odor that becomes pleasant at extreme dilutions. [1]

| Compound name | Compound type | Threshold (ppm) | Typical occurrence |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5-Ethylidene-2-norbornene | alkene | 0.00014 | synthetic |

| Trimethylamine | amine | 0.00003 | spoiled fish |

| Isovaleric acid | carboxylic acid | 0.000078 | vomit |

| tert-Butyl mercaptan | thiol | 0.0000029 | Natural gas |

| Dimethylsulfide | thioether | 0.003 | putrified flesh |

| Compound name | Fragrance | Natural occurrence | Chemical structure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trimethylamine | Fishy Ammonia | Spoiled fish | |

| Putrescine | Rotting flesh | Rotting flesh | |

| Cadaverine | Rotting flesh | Rotting flesh | |

| Pyridine | Fishy | Belladonna | |

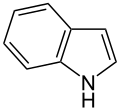

| Indole | Fecal Flowery | Feces Jasmine |  |

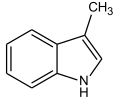

| Skatole | Fecal Flowery | Feces (diluted) Orange Blossoms |  |

Sulfur is odorless, but many sulfur compounds have unpleasant odors. Prominent is hydrogen sulfide, which results from decaying proteins and is a major nuisance associated with the paper industry. [3] It is nonetheless an important signalling molecule in nature. [4] The vast inventory of organosulfur compounds typically have unpleasant odors. Thioacetone, a mixture of lightly studied organosulfur compounds is infamous for its strong stench.

A notable exception to the malodorous nature of thiols is grapefruit mercaptan, the odor of grapefruits. Furan-2-ylmethanethiol (aka furfuryl mercaptan, is the principal odor of roasted coffee. [5] Allyl thiol CH2=CHCH2SH) is a component of garlic breath. [6] (Methylthio)methanethiol (CH3SCH2SH) is found in male mouse urine and functions as a semiochemical for female mice. It has a strong garlic odor. [7]

The foul odors of thiols is exploited by skunks as components of their defensive spray. Gas chromatographic analysis of the spray from the spotted skunk (Spilogal putorius), revealed these three thiols: (E)-2-butene-1-thiol, 3-methyl-1-butanethiol, and 2-phenylethanethiol. [8] [9]

Volatile organophosphorus and organoarsenic compounds characteristically have distinctive odors. Sometimes claimed as the first organometallic compound, Cadet's fuming liquid was reported in 1760 to smell like garlic. [10] It consisted mostly of dicacodyl (((CH3)2As)2) and cacodyl oxide (((CH3)2As)2O). The methylphosphines ((CH3)PH2, (CH3)2PH, and (CH3)3P have a garlic-metallic odors. [11]

In contrast to the pleasant, often fruity odor of carboxylic acid esters, the parent carboxylic acids have unpleasant odors. Butyric acid is associated with spoiled dairy products. The C-5 acids, valeric acids are produced in the human gut. [12]

Focusing on a prevalent stench compound, hydrogen sulfide is highly toxic. The risk of poisoning is made worse because it induces loss of olfactory perception at the ppm level. [13] With regards to remediation, hydrogen sulfide is readily trapped and destroyed by base and air. Similar treatment also applies to thiols. [3]

In the design of processes that have a potential to produce odor pollution, instruments and expert panels are employed to measure the intensity of odors. However, most instruments that measure concentration of air pollutants, whether via infrared analysis, colorimetry, adsorption, absorption, or surface tension, are limited in the compounds they can identify and have limited lower detection limits. For these reasons, human observation is often more reliable for evaluating odorous compounds. Stench compounds such as hydrogen sulfide are more readily detectable and are often given much lower acceptable concentrations in legal air quality standards, and counteraction is necessary to remove them from pollution streams to avoid irritation to the broader environment. [14]