Usage

Thomas Nagel, in The Absurd:

Yet humans have the special capacity to step back and survey themselves, and the lives to which they are committed... Without developing the illusion that they are able to escape from their highly specific and idiosyncratic position, they can view it sub specie aeternitatis—and the view is at once sobering and comical.

and later in that article:

If sub specie aeternitatis there is no reason to believe that anything matters, then that does not matter either, and we can approach our absurd lives with irony instead of heroism or despair. [3]

Stephen Halliwell refers to Aristotle's development away from a view of life sub specie aeternitatis:

But if Aristotle has no room in his mature thinking for the decadence that refuses to take anything in life seriously, this needs to be distinguished from the fact that in his (probably early) Protrepticus he was able to adopt the platonising judgement that, sub specie aeternitatis, everything that supposedly matters in human life 'is a laughing-stock (gelōs) and worthless'. [4]

Ludwig Wittgenstein, in Notebooks 1914-1916:

The work of art is the object seen sub specie aeternitatis; and the good life is the world seen sub specie aeternitatis. This is the connection between art and ethics. [5]

Later, in Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus:

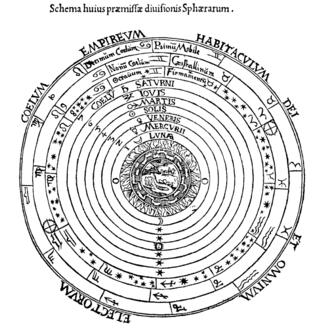

6.45 To view the world sub specie aeterni is to view it as a whole—a limited whole. Feeling the world as a limited whole—it is this that is mystical. [6]

Viktor E. Frankl, in Man's Search for Meaning :

It is a peculiarity of man that he can only live by looking to the future—sub specie aeternitatis. [7]

Dietrich Bonhoeffer wrote:

From all this it now follows that the content of ethical problems can never be discussed in a Christian light; the possibility of erecting generally valid principles simply does not exist, because each moment, lived in God’s sight, can bring an unexpected decision. Thus only one thing can be repeated again and again, also in our time: in ethical decisions a man must consider his action sub specie aeternitatis and then, no matter how it proceeds, it will proceed rightly. [8]

In his novel The Ordeal of Gilbert Pinfold , Evelyn Waugh describes Pinfold:

He wished no one ill, but looked at the world sub specie aeternitatis and he found it flat as a map; except when, rather often, personal annoyance intruded. [9]

John Rawls wrote, in the final paragraph of A Theory of Justice :

Thus to see our place in society from the perspective of this position is to see it sub specie aeternitatis: it is to regard the human situation not only from all social but also from all temporal points of view. [10]

Bernard Williams, in Utilitarianism: For and Against :

Philosophers ... repeatedly urge us to view the world sub specie aeternitatis, but for most human purposes that is not a good species to view it under. [11]

Peter L. Berger, in The Sacred Canopy:

Just as institutions may be relativized and thus humanized when viewed sub specie aeternitatis, so may the roles representing these institutions. [12]

Luciano Floridi, in The Philosophy of Information:

First, sub specie aeternitatis, science is still in its puberty, when some hiccups are not necessarily evidence of any serious sickness. [13]

Christopher Dawson, in The Christian View of History:

For the Christian view of history is a vision of history sub specie aeternitatis, an interpretation of time in terms of eternity and of human events in the light of divine revelation. And thus Christian history is inevitably apocalyptic, and the apocalypse is the Christian substitute for the secular philosophies of history. [14]

Michael Oakeshott, in Historical Experience:

Pretending to organize and elucidate the real world of experience sub specie aeternitatis, history succeeds only in organizing it sub specie praeteritorum. [15]

Carl Jung, in Memories, Dreams, Reflections :

What we are to our inward vision, and what man appears to be sub specie aeternitatis, can only be expressed by way of myth. [16]

Philip K. Dick, in Galactic Pot-Healer & Do androids dream of electric sheep :

The stewardess began setting up the SSA machine in a rapid, efficient fashion, meanwhile explaining it. "SSA stands for sub specie aeternitatis; that is, something seen outside of time. Now, many individuals imagine that an SSA machine can see into the future, that it is precognitive. This is not true. The mechanism, basically a computer, is attached via electrodes to both your brains and it swiftly stores up immense quantities of data about each of you. It then synthesizes these data and, on a probability basis, extrapolates as to what would most likely become of you both if you were, for example, joined in marriage, or perhaps living together. [17]

Ludwig von Mises, in Human Action: A Treatise on Economics :

It is customary to blame the economists for an alleged disregard of history. The economists, it is contended, consider the market economy as the ideal and eternal pattern of social cooperation. They concentrate their studies upon investigating the conditions of the market economy and neglect everything else. They do not bother about the fact that capitalism emerged only in the last two hundred years and that even today it is restricted to a comparatively small area of the earth's surface and to a minority of peoples. There were and are, say these critics, other civilizations with a different mentality and different modes of conducting economic affairs. Capitalism is, when seen sub specie aeternitatis, a passing phenomenon, an ephemeral stage of historical evolution, just the transition from precapitalistic ages to a postcapitalistic future. All these criticisms are spurious.... [18]

Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk, in Talks with T.G. Masaryk by Karel Čapek:

Many modern man is afraid of death, he is too luxurious—his life is not great drama, he just wants to food and enjoyment; unbeliever is not there enough trust and dedication. Modern suicide and the fear of death—these two are related, as related to fear and escape. But it would be a problem for themselves. When I think of immortallity, so I do not think of death and what happens after, but rather on life and its contents. It immortally stems from the richness and value of human life, the human soul. The man himself, one man is more valuable as a spiritual being. And immortal soul also follows from the recognition of God, faith in the world order and justice. It would not be justice, there would be perfect equality without eternal souls. Immortality are experiencing now, in this life; we have no experience of life after death, but we have, we have the experience now that life truly and fully human only live sub specie aeternitatis. That experience ultimately depends on us, on how we live, what we are full, and what of his life here, we look to do. Just as the soul of the eternal souls live life fully and honestly. The existence of the soul is the true foundation of democracy: the eternal can not be indifferent to the eternal, immortal immortal is equal. From charity receives its special—he is said metaphysical—sense. [19]

Rebecca Goldstein in Plato at the Googleplex: Why Philosophy Won't Go Away:

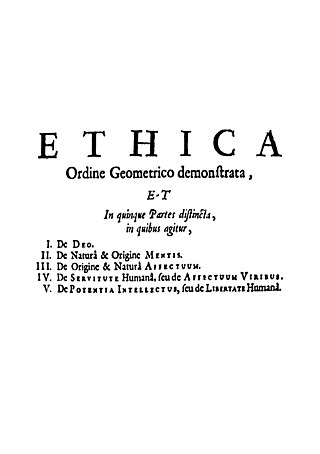

We are immortal only to the extent that we allow our own selves to be rationalized by the sublime ontological rationality, ordering our own processes of thinking, desiring, and acting in accordance with the perfect proportions realized in the cosmos. We are then, while in this life, living sub specie aeternitatis, as Spinoza was to put it, expanding our finitude to encapture as much of infinity as we are able. [20]

In the article on Spinoza from the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy:

Sense experience alone could never provide the information conveyed by an adequate idea. The senses present things only as they appear from a given perspective at a given moment in time. An adequate idea, on the other hand, by showing how a thing follows necessarily from one or another of God's attributes, presents it in its "eternal" aspects—sub specie aeternitatis, as Spinoza puts it—without any relation to time. "It is of the nature of Reason to regard things as necessary and not as contingent. And Reason perceives this necessity of things truly, i.e., as it is in itself. But this necessity of things is the very necessity of God's eternal nature. Therefore, it is of the nature of Reason to regard things under this species of eternity" (IIp44). The third kind of knowledge, intuition, takes what is known by Reason and grasps it in a single act of the mind. [21]

As a play on the expression, J. L. Austin puns on it in order to discuss the very fallibility of human knowledge:

'Being sure it's real' is no more proof against miracles or outrages of nature than anything else is or, sub specie humanitatis, can be. If we have made sure it's a goldfinch, and a real goldfinch, and then in the future it does something outrageous (explodes, quotes Mrs. Woolf, or what not), we don't say we were wrong to say it was a goldfinch, we don't know what to say. Words literally fail us: 'What would you have said?' 'What are we to say now?' 'What would you say?' When I have made sure it's a real goldfinch (not stuffed, corroborated by the disinterested, &c.) then I am not 'predicting' in saying it's a real goldfinch, and in a very good sense I can't be proved wrong whatever happens. It seems a serious mistake to suppose that language (or most language, language about real things) is 'predictive' in such a way that the future can always prove it wrong. What the future can always do, is to make us revise our ideas about goldfinches or real goldfinches or anything else. [22]

Julian Huxley suggested an alternative: "in the light of evolution". [23]