A tax is a compulsory financial charge or some other type of levy imposed on a taxpayer by a governmental organization in order to fund government spending and various public expenditures. A failure to pay, along with evasion of or resistance to taxation, is punishable by law. Taxes consist of direct or indirect taxes and may be paid in money or as its labour equivalent. The first known taxation took place in Ancient Egypt around 3000–2800 BC.

In economics, elasticity is the measurement of the percentage change of one economic variable in response to a change in another.

Conspicuous consumption is the spending of money on and the acquiring of luxury goods and services to publicly display economic power of the income or of the accumulated wealth of the buyer. To the conspicuous consumer, such a public display of discretionary economic power is a means of either attaining or maintaining a given social status.

A good's price elasticity of demand is a measure of how sensitive the quantity demanded of it is to its price. When the price rises, quantity demanded falls for almost any good, but it falls more for some than for others. The price elasticity gives the percentage change in quantity demanded when there is a one percent increase in price, holding everything else constant. If the elasticity is -2, that means a one percent price rise leads to a two percent decline in quantity demanded. Other elasticities measure how the quantity demanded changes with other variables.

The theory of consumer choice is the branch of microeconomics that relates preferences to consumption expenditures and to consumer demand curves. It analyzes how consumers maximize the desirability of their consumption as measured by their preferences subject to limitations on their expenditures, by maximizing utility subject to a consumer budget constraint.

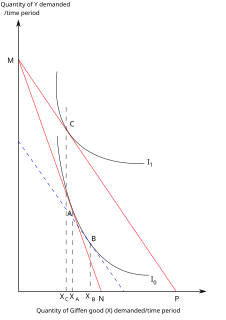

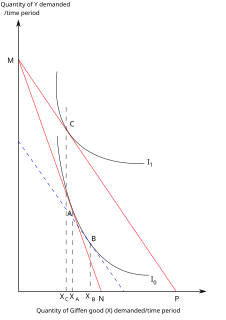

In economics and consumer theory, a Giffen good is a product that people consume more of as the price rises and vice versa—violating the basic law of demand in microeconomics. For any other sort of good, as the price of the good rises, the substitution effect makes consumers purchase less of it, and more of substitute goods; for most goods, the income effect reinforces this decline in demand for the good. But a Giffen good is so strongly an inferior good in the minds of consumers that this contrary income effect more than offsets the substitution effect, and the net effect of the good's price rise is to increase demand for it. Also known as Giffen Paradox. A Giffen good is considered to be the opposite of an ordinary good.

In economics, an inferior good is a good whose demand decreases when consumer income rises, unlike normal goods, for which the opposite is observed. Normal goods are those goods for which the demand rises as consumer income rises.

In economics, a normal good is any good for which demand increases when income increases, i.e. with a positive income elasticity of demand.

In microeconomics, two goods are substitutes if the products could be used for the same purpose by the consumers. That is, a consumer perceives both goods as similar or comparable, so that having more of one good causes the consumer to desire less of the other good. Contrary to complementary goods and independent goods, substitute goods may replace each other in use due to changing economic conditions.

In microeconomics, an Engel curve describes how household expenditure on a particular good or service varies with household income. There are two varieties of Engel curves. Budget share Engel curves describe how the proportion of household income spent on a good varies with income. Alternatively, Engel curves can also describe how real expenditure varies with household income. They are named after the German statistician Ernst Engel (1821–1896), who was the first to investigate this relationship between goods expenditure and income systematically in 1857. The best-known single result from the article is Engel's law which states that the poorer a family is, the larger the budget share it spends on nourishment.

In economics and particularly in consumer choice theory, the income-consumption curve is a curve in a graph in which the quantities of two goods are plotted on the two axes; the curve is the locus of points showing the consumption bundles chosen at each of various levels of income.

In economics, a luxury good is a good for which demand increases more than proportionally as income rises, so that expenditures on the good become a greater proportion of overall spending.

In economics, a demand curve is a graph depicting the relationship between the price of a certain commodity and the quantity of that commodity that is demanded at that price. Demand curves may be used to model the price-quantity relationship for an individual consumer, or more commonly for all consumers in a particular market. It is generally assumed that demand curves are downward-sloping, as shown in the adjacent image. This is because of the law of demand: for most goods, the quantity demanded will decrease in response to an increase in price, and will increase in response to a decrease in price.

The wealth effect is the change in spending that accompanies a change in perceived wealth. Usually the wealth effect is positive: spending changes in the same direction as perceived wealth.

The wealth elasticity of demand, in microeconomics and macroeconomics, is the proportional change in the consumption of a good relative to a change in consumers' wealth. Measuring and accounting for the variability in this elasticity is a continuing problem in behavioral finance and consumer theory.

In economics, demand is the quantity of a good that consumers are willing and able to purchase at various prices during a given period of time. The relationship between price and quantity demanded is also called the demand curve. Demand for a specific item is a function of an item's perceived necessity, price, perceived quality, convenience, available alternatives, purchasers' disposable income and tastes, and many other factors.

Optimal tax theory or the theory of optimal taxation is the study of designing and implementing a tax that maximises a social welfare function subject to economic constraints. The social welfare function used is typically a function of individuals' utilities, most commonly some form of utilitarian function, so the tax system is chosen to maximise the aggregate of individual utilities. Tax revenue is required to fund the provision of public goods and other government services, as well as for redistribution from rich to poor individuals. However, most taxes distort individual behavior, because the activity that is taxed becomes relatively less desirable; for instance, taxes on labour income reduce the incentive to work. The optimization problem involves minimizing the distortions caused by taxation, while achieving desired levels of redistribution and revenue. Some taxes are thought to be less distorting, such as lump-sum taxes and Pigouvian taxes, where the market consumption of a good is inefficient and a tax brings consumption closer to the efficient level.

In economics, a necessity good or a necessary good is a type of normal good. Necessity goods are products and services that consumers will buy regardless of the changes in their income levels, therefore making these products less sensitive to income change. Examples include repetitive purchases of different durations such as haircuts, habits including tobacco, everday essentials such as electricity and water, and critical medicine such as insulin. As for any other normal good, an income rise will lead to a rise in demand, but the increase for a necessity good is less than proportional to the rise in income, so the proportion of expenditure on these goods falls as income rises. If income elasticity of demand is lower than unity, it is a necessity good. This observation for food, known as Engel's law, states that as income rises, the proportion of income spent on food falls, even if absolute expenditure on food rises. This makes the income elasticity of demand for food between zero and one.

In economics, the income elasticity of demand is the responsiveness of the quantity demanded for a good to a change in consumer income. It is measured as the ratio of the percentage change in quantity demanded to the percentage change in income. If a 10% increase in Mr. Ruskin Smith's income causes him to buy 20% more bacon, Smith's income elasticity of demand for bacon is 20%/10% = 2.

In any technical subject, words commonly used in everyday life acquire very specific technical meanings, and confusion can arise when someone is uncertain of the intended meaning of a word. This article explains the differences in meaning between some technical terms used in economics and the corresponding terms in everyday usage.