Fable is a literary genre defined as a succinct fictional story, in prose or verse, that features animals, legendary creatures, plants, inanimate objects, or forces of nature that are anthropomorphized, and that illustrates or leads to a particular moral lesson, which may at the end be added explicitly as a concise maxim or saying.

Aesop's Fables, or the Aesopica, is a collection of fables credited to Aesop, a slave and storyteller who lived in ancient Greece between 620 and 564 BCE. Of varied and unclear origins, the stories associated with his name have descended to modern times through a number of sources and continue to be reinterpreted in different verbal registers and in popular as well as artistic media.

"The Tortoise and the Hare" is one of Aesop's Fables and is numbered 226 in the Perry Index. The account of a race between unequal partners has attracted conflicting interpretations. The fable itself is a variant of a common folktale theme in which ingenuity and trickery are employed to overcome a stronger opponent.

The Lion and the Mouse is one of Aesop's Fables, numbered 150 in the Perry Index. There are also Eastern variants of the story, all of which demonstrate mutual dependence regardless of size or status. In the Renaissance the fable was provided with a sequel condemning social ambition.

"The Town Mouse and the Country Mouse" is one of Aesop's Fables. It is number 352 in the Perry Index and type 112 in Aarne–Thompson's folk tale index. Like several other elements in Aesop's fables, "town mouse and country mouse" has become an English idiom.

The Dog and Its Reflection is one of Aesop's Fables and is numbered 133 in the Perry Index. The Greek language original was retold in Latin and in this way was spread across Europe, teaching the lesson to be contented with what one has and not to relinquish substance for shadow. There also exist Indian variants of the story. The morals at the end of the fable have provided both English and French with proverbs and the story has been applied to a variety of social situations.

The Scorpion and the Frog is an animal fable which teaches that vicious people cannot resist hurting others even when it is not in their own interests. This fable seems to have emerged in Russia in the early 20th century.

The Farmer and the Viper is one of Aesop's Fables, numbered 176 in the Perry Index. It has the moral that kindness to evil will be met by betrayal and is the source of the idiom "to nourish a viper in one's bosom". The fable is not to be confused with The Snake and the Farmer, which looks back to a situation when friendship was possible between the two.

Belling the Cat is a fable also known under the titles The Bell and the Cat and The Mice in Council. In the story, a group of mice agree to attach a bell to a cat's neck to warn of its approach in the future, but they fail to find a volunteer to perform the job. The term has become an idiom describing a group of persons, each agreeing to perform an impossibly difficult task under the misapprehension that someone else will be chosen to run the risks and endure the hardship of actual accomplishment.

The Tortoise and the Birds is a fable of probable folk origin, early versions of which are found in both India and Greece. There are also African variants. The moral lessons to be learned from these differ and depend on the context in which they are told.

The Morall Fabillis of Esope the Phrygian is a work of Northern Renaissance literature composed in Middle Scots by the fifteenth century Scottish makar, Robert Henryson. It is a cycle of thirteen connected narrative poems based on fables from the European tradition. The drama of the cycle exploits a set of complex moral dilemmas through the figure of animals representing a full range of human psychology. As the work progresses, the stories and situations become increasingly dark.

The drowned woman and her husband is a story found in Mediaeval jest-books that entered the fable tradition in the 16th century. It was occasionally included in collections of Aesop's Fables but never became established as such and has no number in the Perry Index. Folk variants in which a contrary wife is sought upstream by her husband after she drowns are catalogued under the Aarne-Thompson classification system as type 1365A.

The Crow or Raven and the Snake or Serpent is one of Aesop's Fables and numbered 128 in the Perry Index. Alternative Greek versions exist and two of these were adopted during the European Renaissance. The fable is not to be confused with the story of this title in the Panchatantra, which is completely different.

Jean de La Fontaine collected fables from a wide variety of sources, both Western and Eastern, and adapted them into French free verse. They were issued under the general title of Fables in several volumes from 1668 to 1694 and are considered classics of French literature. Humorous, nuanced and ironical, they were originally aimed at adults but then entered the educational system and were required learning for school children.

The Fox and the Weasel is a title used to cover a complex of fables in which a number of other animals figure in a story with the same basic situation involving the unfortunate effects of greed. Of Greek origin, it is counted as one of Aesop's Fables and is numbered 24 in the Perry Index.

"The Paddock and the Mouse" is a poem by the 15th-century Scottish poet Robert Henryson and part of his collection of moral fables known as the Morall Fabillis of Esope the Phrygian. It is written in Middle Scots. As with the other tales in the collection, appended to it is a moralitas which elaborates on the moral that the fable is supposed to contain.

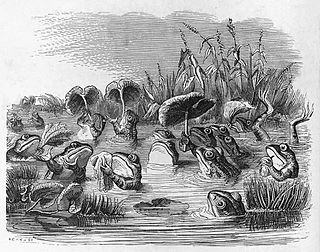

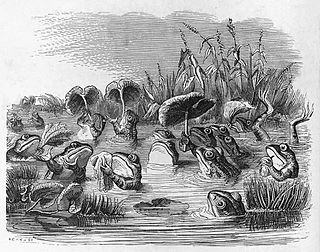

The Frogs and the Sun is one of Aesop's Fables and is numbered 314 in the Perry Index. It has been given political applications since Classical times.

Hercules and the Wagoner or Hercules and the Carter is a fable credited to Aesop. It is associated with the proverb "God helps those who help themselves", variations on which are found in other ancient Greek authors.

The Kite and the Doves is a political fable ascribed to Aesop that is numbered 486 in the Perry Index. During the Middle Ages the fable was modified by the introduction of a hawk as an additional character, followed by a change in the moral drawn from it.

The Frog and the Fox is one of Aesop's Fables and is numbered 289 in the Perry Index. It takes the form of a humorous anecdote told against quack doctors.