René François Ghislain Magritte was a Belgian surrealist artist known for his depictions of familiar objects in unfamiliar, unexpected contexts, which often provoked questions about the nature and boundaries of reality and representation. His imagery has influenced pop art, minimalist art, and conceptual art.

André Albert Auguste Delvaux was a Belgian film director. He co-founded the film school INSAS in 1962 and is regarded as the founder of the Belgian national cinema. Adapting works by writers such as Johan Daisne, Julien Gracq and Marguerite Yourcenar, he received international attention for directing magic realist films.

Giuseppe Maria Alberto Giorgio de Chirico was an Italian artist and writer born in Greece. In the years before World War I, he founded the scuola metafisica art movement, which profoundly influenced the surrealists. His best-known works often feature Roman arcades, long shadows, mannequins, trains, and illogical perspective. His imagery reflects his affinity for the philosophy of Arthur Schopenhauer and of Friedrich Nietzsche, and for the mythology of his birthplace.

Paul Delvaux was a Belgian painter noted for his dream-like scenes of women, classical architecture, trains and train stations, and skeletons, often in combination. He is often considered a surrealist, although he only briefly identified with the Surrealist movement. He was influenced by the works of Giorgio de Chirico and René Magritte, but developed his own fantastical subjects and hyper-realistic styling, combining the detailed classical beauty of academic painting with the bizarre juxtapositions of surrealism.

Alfred Émile Léopold Stevens was a Belgian painter, known for his paintings of elegant modern women. In their realistic style and careful finish, his works reveal the influence of 17th-century Dutch genre painting. After gaining attention early in his career with a social realist painting depicting the plight of poor vagrants, he achieved great critical and popular success with his scenes of upper-middle class Parisian life.

Watermael-Boitsfort or Watermaal-Bosvoorde, often simply called Boitsfort in French or Bosvoorde in Dutch, is one of the 19 municipalities of the Brussels-Capital Region, Belgium. Located in the south-eastern part of the region, it is bordered by Auderghem, the City of Brussels, Ixelles, and Uccle, as well as the Flemish municipalities of Hoeilaart, Overijse and Sint-Genesius-Rode. In common with all of Brussels' municipalities, it is legally bilingual (French–Dutch).

Metaphysical Interior with Large Factory is an oil-on-canvas painting by the Italian metaphysical painter Giorgio de Chirico, from 1916. It is part of a series that extended late into de Chirico's career.

The Royal Academy of Fine Arts of Brussels is an art school in Brussels, Belgium, founded in 1711. Starting from modest beginnings in a single room in Brussels' Town Hall, it has since 1876 been operating from a former convent and orphanage in the Rue du Midi/Zuidstraat, which was converted by the architect Victor Jamaer. The school has played an important role in training leading local artists.

The Museum of Fine Arts of Lyon is a municipal museum of fine arts in the French city of Lyon. Located near the Place des Terreaux, it is housed in a former Benedictine convent which was active during the 17th and 18th centuries. It was restored between 1988, and 1998, remaining open to visitors throughout this time despite the ongoing restoration works. Its collections range from ancient Egyptian antiquities to the Modern art period, making the museum one of the most important in Europe. It also hosts important exhibitions of art, for example the exhibitions of works by Georges Braque and Henri Laurens in the second half of 2005, and another on the work of Théodore Géricault from April to July 2006. It is one of the largest art museums in France.

Laurent Delvaux was a Flemish sculptor. After a successful international career that brought him to London and Rome, he returned to the Austrian Netherlands where he was a sculptor to the court. Delvaux was a transitional figure between the Baroque and Neo-classicism.

The Apotheosis of Homer is a grand 1827 painting by the French Neoclassical artist Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, now exhibited at the Louvre as INV 5417. The symmetrical composition depicts Homer being crowned by a winged figure personifying Victory or the Universe. Forty-four additional figures pay homage to the poet in a kind of classical confession of faith.

Marcel Paquet was a Belgian philosopher. The most important influences on his thought were Spinoza, Kant, Hegel, Nietzsche, Heidegger and Michel Foucault.

The Great Sirens is a large 1947 painting by the Belgian painter Paul Delvaux in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, in New York.

The Road to Rome is a 1979 painting by the Belgian painter Paul Delvaux. It depicts a European town square in twilight, with a number of women, many of whom are nude or semi-nude, scattered around the scene. Three high, open doors stand upright along the walkway.

The Sacrifice of Iphigenia is a 1968 painting by the Belgian artist Paul Delvaux. Inspired by Iphigenia's sacrifice in Greek mythology, it depicts five people on a boardwalk. In the foreground are three women, two of whom might be the same person who watches herself, and behind them appears to be a scene of human sacrifice where a man overlooks a woman with an exposed breast.

Procession in Lace is a painting executed by the Belgian artist Paul Delvaux in 1936. It shows a group of women walking toward a Roman triumphal arch. It was one of the first paintings in which Delvaux drew inspiration from Giorgio de Chirico and painted women reminiscent of mannequins, something he would continue to do throughout his career. Art historians have highlighted the painting's theatricality and described it as one of Delvaux's first major works.

Sleeping Venus is a 1944 painting by the Belgian artist Paul Delvaux. It depicts a reclining Venus surrounded by anguished people at a town square with classical buildings. It was painted in Brussels while the city was bombed during World War II and Delvaux wanted to contrast the psychological drama of the moment with the calm Venus. The painting has been in the collection of Tate in London since 1957.

The Paul Delvaux Museum is a private museum in Saint-Idesbald, Belgium, devoted to the life and works of the painter Paul Delvaux. It was established in 1982 by the Foundation Paul Delvaux and houses the world's largest collection of Delvaux's works.

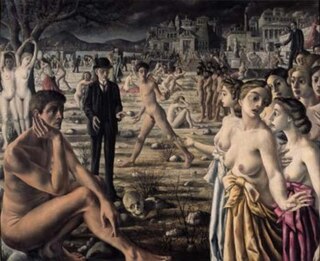

The Anxious City is a painting made by Paul Delvaux in 1940–1941. It depicts a large number of upset people, most of whom are nude or partially nude, in front of a lake and classical structures. Among the characters who stand out are a naked self-portrait of Delvaux, a man in a bowler hat and a group of bare-breasted women. The man with the bowler hat made his debut in The Anxious City and would appear in several other Delvaux paintings.