The Olmecs were the earliest known major Mesoamerican civilization. Following a progressive development in Soconusco, they occupied the tropical lowlands of the modern-day Mexican states of Veracruz and Tabasco. It has been speculated that the Olmecs derived in part from the neighboring Mokaya or Mixe–Zoque cultures.

Olmec figurines are archetypical figurines produced by the Formative Period inhabitants of Mesoamerica. While not all of these figurines were produced in the Olmec heartland, they bear the hallmarks and motifs of Olmec culture. While the extent of Olmec control over the areas beyond their heartland is not yet known, Formative Period figurines with Olmec motifs were widespread in the centuries from 1000 to 500 BCE, showing a consistency of style and subject throughout nearly all of Mesoamerica.

La Venta is a pre-Columbian archaeological site of the Olmec civilization located in the present-day Mexican state of Tabasco. Some of the artifacts have been moved to the museum "Parque - Museo de La Venta", which is in nearby Villahermosa, the capital of Tabasco.

The religion of the Olmec people significantly influenced the social development and mythological world view of Mesoamerica. Scholars have seen echoes of Olmec supernatural in the subsequent religions and mythologies of nearly all later pre-Columbian era cultures.

Teopantecuanitlan is an archaeological site in the Mexican state of Guerrero that represents an unexpectedly early development of complex society for the region. The site dates to the Early to Middle Formative Periods, with the archaeological evidence indicating that some kind of connection existed between Teopantecuanitlan and the Olmec heartland of the Gulf Coast. Prior to the discovery of Teopantecuanitlan in the early 1980s, little was known about the region's sociocultural development and organization during the Formative period.

Tres Zapotes is a Mesoamerican archaeological site located in the south-central Gulf Lowlands of Mexico in the Papaloapan River plain. Tres Zapotes is sometimes referred to as the third major Olmec capital, but the Olmec phase is only a portion of the site's history, which continued through the Epi-Olmec and Classic Veracruz cultural periods.

San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán or San Lorenzo is the collective name for three related archaeological sites—San Lorenzo, Tenochtitlán and Potrero Nuevo—located in the southeast portion of the Mexican state of Veracruz. Along with La Venta and Tres Zapotes, it was one of the three major cities of the Olmec, and the major center of Olmec culture from 1400 BCE to 900 BCE. San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán is best known today for the colossal stone heads unearthed there, the greatest of which weigh 28 metric tons or more and are 3 metres (9.8 ft) high.

Michael Douglas Coe was an American archaeologist, anthropologist, epigrapher, and author. He is known for his research on pre-Columbian Mesoamerica, particularly the Maya, and was among the foremost Mayanists of the late twentieth century. He specialised in comparative studies of ancient tropical forest civilizations, such as those of Central America and Southeast Asia. He held the chair of Charles J. MacCurdy Professor of Anthropology, Emeritus, Yale University, and was curator emeritus of the Anthropology collection in the Peabody Museum of Natural History, where he had been curator from 1968 to 1994.

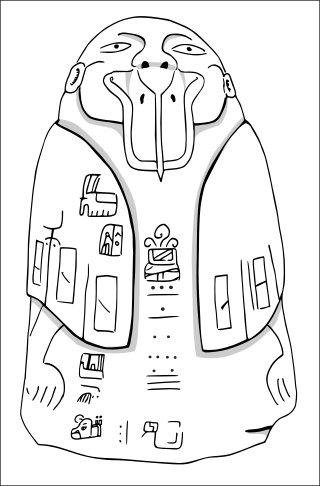

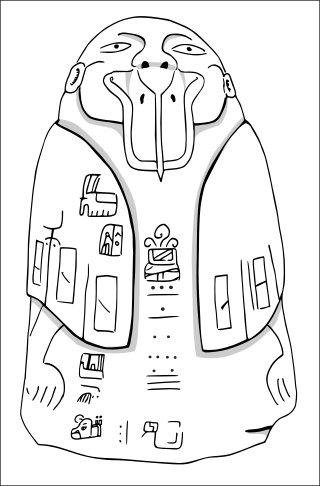

The Tuxtla Statuette is a small 6.3 inch (16 cm) rounded greenstone figurine, carved to resemble a squat, bullet-shaped human with a duck-like bill and wings. Most researchers believe the statuette represents a shaman wearing a bird mask and bird cloak. It is incised with 75 glyphs of the Epi-Olmec or Isthmian script, one of the few extant examples of this very early Mesoamerican writing system.

La Mojarra Stela 1 is a Mesoamerican carved monument (stela) dating from 156 CE. It was discovered in 1986, pulled from the Acula River near La Mojarra, Veracruz, Mexico, not far from the Tres Zapotes archaeological site. The 4+1⁄2-foot-wide (1.4 m) by 6+1⁄2-foot-high (2.0 m), four-ton limestone slab contains about 535 glyphs of the Isthmian script. One of Mesoamerica's earliest known written records, this Epi-Olmec culture monument not only recorded this ruler's achievements, but placed them within a cosmological framework of calendars and astronomical events.

The Olmec heartland is the southern portion of Mexico's Gulf Coast region between the Tuxtla mountains and the Olmec archaeological site of La Venta, extending roughly 80 km inland from the Gulf of Mexico coastline at its deepest. It is today, as it was during the height of the Olmec civilization, a tropical lowland forest environment, crossed by meandering rivers.

The causes and degree of Olmec influences on Mesoamerican cultures has been a subject of debate over many decades. Although the Olmecs are considered to be perhaps the earliest Mesoamerican civilization, there are questions concerning how and how much the Olmecs influenced cultures outside the Olmec heartland. This debate is succinctly, if simplistically, framed by the title of a 2005 The New York Times article: “Mother Culture, or Only a Sister?”.

Oxtotitlán is a natural rock shelter and archaeological site in Chilapa de Álvarez, Mexican state of Guerrero that contains murals linked to the Olmec motifs and iconography. Along with the nearby Juxtlahuaca cave, the Oxtotitlán rock paintings represent the "earliest sophisticated painted art known in Mesoamerica", thus far. Unlike Juxtlahuaca, however, the Oxtotitlán paintings are not deep in a cave system but rather occupy two shallow grottos on a cliff face.

Las Limas Monument 1, also known as the Las Limas figure or the Señor de las Limas, is a 55 centimetres (22 in) greenstone figure of a youth holding a limp were-jaguar baby. Found in the State of Veracruz, Mexico, in the Olmec heartland, the statue is famous for its incised representations of Olmec supernaturals. It is the largest known greenstone sculpture.

The werejaguar was both an Olmec motif and a supernatural entity, perhaps a deity.

Classic Veracruz culture refers to a cultural area in the north and central areas of the present-day Mexican state of Veracruz, a culture that existed from roughly 100 to 1000 CE, or during the Classic era.

The Epi-Olmec culture was a cultural area in the central region of the present-day Mexican state of Veracruz. Concentrated in the Papaloapan River basin, a culture that existed during the Late Formative period, from roughly 300 BCE to roughly 250 CE. Epi-Olmec was a successor culture to the Olmec, hence the prefix "epi-" or "post-". Although Epi-Olmec did not attain the far-reaching achievements of that earlier culture, it did realize, with its sophisticated calendrics and writing system, a level of cultural complexity unknown to the Olmecs.

Olmec hieroglyphs are a set of glyphs developed within the Olmec culture. The Olmecs were the earliest known major Mesoamerican civilization, flourishing during the formative period in the tropical lowlands of the modern-day Mexican states of Veracruz and Tabasco. The subsequent Epi-Olmec culture, was a successor culture to the Olmec and featured the Isthmian script, which has been characterized as a full-fledged writing system, though with its partial decipherment being disputed.

Xochipala is a minor archaeological site in the Mexican state of Guerrero, whose name has become attached, somewhat erroneously, to a style of Formative Period figurines and pottery from 1500 to 200 BCE. The archaeological site is much later and belongs to the Classic and Postclassic eras, approximately 200–1400 CE.

The Olmec colossal heads are stone representations of human heads sculpted from large basalt boulders. They range in height from 1.17 to 3.4 metres. The heads date from at least 900 BC and are a distinctive feature of the Olmec civilization of ancient Mesoamerica. All portray mature individuals with fleshy cheeks, flat noses, and slightly-crossed eyes; their physical characteristics correspond to a type that is still common among the inhabitants of Tabasco and Veracruz. The backs of the monuments often are flat. The boulders were brought from the Sierra de Los Tuxtlas mountains of Veracruz. Given that the extremely large slabs of stone used in their production were transported over large distances, requiring a great deal of human effort and resources, it is thought that the monuments represent portraits of powerful individual Olmec rulers. Each of the known examples has a distinctive headdress. The heads were variously arranged in lines or groups at major Olmec centres, but the method and logistics used to transport the stone to these sites remain unclear. They all display distinctive headgear and one theory is that these were worn as protective helmets, maybe worn for war or to take part in a ceremonial Mesoamerican ballgame.