Lev Davidovich Bronstein, better known as Leon Trotsky, was a Soviet politician, revolutionary, and political theorist. He was a central figure in the 1905 Revolution, October Revolution of 1917, Russian Civil War, and establishment of the Soviet Union. In the early years of Soviet Russia, Trotsky and Vladimir Lenin were widely considered its two most prominent figures, and Trotsky was Lenin's de facto second-in-command in the government from 1917 to 1923. Ideologically a Marxist and a Leninist, Trotsky's thought inspired a school of Marxism known as Trotskyism.

Leninism is a political ideology developed by Russian Marxist revolutionary Vladimir Lenin that proposes the establishment of the dictatorship of the proletariat led by a revolutionary vanguard party as the political prelude to the establishment of communism. Lenin's ideological contributions to the Marxist ideology relate to his theories on the party, imperialism, the state, and revolution. The function of the Leninist vanguard party is to provide the working classes with the political consciousness and revolutionary leadership necessary to depose capitalism.

Trotskyism is the political ideology and branch of Marxism developed by Russian revolutionary and intellectual Leon Trotsky along with some other members of the Left Opposition and the Fourth International. Trotsky described himself as an orthodox Marxist, a revolutionary Marxist, and a Bolshevik–Leninist as well as a follower of Karl Marx, Frederick Engels, Vladimir Lenin, Karl Liebknecht, and Rosa Luxemburg. His relations with Lenin have been a source of intense historical debate. However, on balance, scholarly opinion among a range of prominent historians and political scientists such as E.H. Carr, Isaac Deutscher, Moshe Lewin, Ronald Suny, Richard B. Day and W. Bruce Lincoln was that Lenin’s desired “heir” would have been a collective responsibility in which Trotsky was placed in "an important role and within which Stalin would be dramatically demoted ".

Working-class culture or proletarian culture is a range of cultures created by or popular among working-class people. The cultures can be contrasted with high culture and folk culture, and are often equated with popular culture and low culture. Working-class culture developed during the Industrial Revolution. Because most of the newly created working class were former peasants, the cultures took on much of the localised folk culture. This was soon altered by the changed conditions of social relationships and the increased mobility of the workforce and later by the marketing of mass-produced cultural artefacts such as prints and ornaments and commercial entertainment such as music hall and cinema.

Victor Serge, born Victor Lvovich Kibalchich, was a Russian writer, poet, Marxist revolutionary, and historian. Originally an anarchist, he joined the Bolsheviks five months after arriving in Petrograd in January 1919 and later worked for the Comintern as a journalist, editor and translator. He was critical of the Stalinist regime and remained a revolutionary Marxist until his death. He was a close supporter of the Left Opposition and associate of Leon Trotsky.

The Ryutin affair was an attempt led by Martemyan Ryutin to remove Joseph Stalin as General Secretary of the All-Union Communist Party (b) (CPSU) in 1932.

Ivar Tenisovich Smilga was a Latvian Bolshevik leader, Soviet politician and economist. He was a member of the Left Opposition in the Soviet Union.

Socialist democracy is a political system that aligns with principles of both socialism and democracy. It includes ideologies such as council communism, democratic socialism, social democracy, and soviet democracy, as well as Marxist democracy like the dictatorship of the proletariat. It was embodied in the Soviet system (1922–1991). It can also denote a system of political party organization like democratic centralism, or a form of democracy espoused by Marxist–Leninist political parties or groups that support one-party states. The Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (1945–1992) styled itself a socialist democracy, as did the People's Republic of Bulgaria (1946–1990) and the Socialist Republic of Romania (1947–1989).

Literature and Revolution is a work of literary criticism from the Marxist standpoint written by Leon Trotsky in 1924. By discussing the various literary trends that were around in Russia between the revolutions of 1905 and 1917, Trotsky analyzed the concrete forces in society, both progressive as well as reactionary, that helped shape the consciousness of writers at the time.

The Left Opposition was a faction within the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) from 1923 to 1927 headed de facto by Leon Trotsky. It was formed by Trotsky to mount a struggle against the perceived bureaucratic degeneration within the party leadership headed by Stalin during the serious illness of the Bolshevik founder Vladimir Lenin and after Lenin's death in January 1924. The Left Opposition advocated for a programme of rapid industrialization, voluntary collectivisation of agriculture, and the expansion of a worker's democracy.

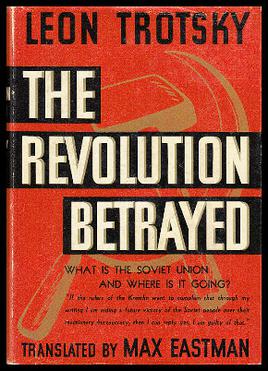

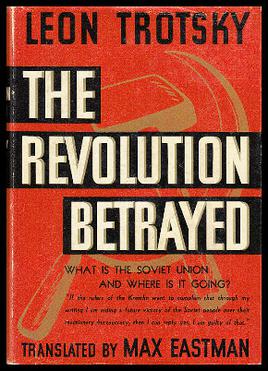

The Revolution Betrayed: What is the Soviet Union and Where is it Going? is a book published in 1936 by the exiled Soviet leader Leon Trotsky. This work analyzed and criticized the course of historical development in the Soviet Union following the death of Vladimir Lenin in 1924 and is regarded as Trotsky's primary work dealing with the nature of Stalinism. The book was written by Trotsky during his exile in Norway and was originally translated into Spanish by Victor Serge. The most widely available English translation is by Max Eastman.

Socialism in one country was a Soviet state policy to strengthen socialism within the country rather than socialism globally. Given the defeats of the 1917–1923 European communist revolutions, Joseph Stalin developed and encouraged the theory of the possibility of constructing socialism in the Soviet Union alone. The theory was eventually adopted as Soviet state policy.

The following is a chronological list of books by Leon Trotsky, a Marxist theoretician, including hardcover and paperback books and pamphlets published during his life and posthumously during the years immediately following his assassination in the northern summer of 1940. Included are the original Russian or German language titles and publication information, as well as the name and publication information of the first English language edition.

Soviet democracy, also called council democracy, is a type of democracy in Marxism, in which the rule of a population is exercised by directly elected soviets. Soviets are directly responsible to their electors and bound by their instructions using a delegate model of representation. Such an imperative mandate is in contrast to a trustee model, in which elected delegates are exclusively responsible to their conscience. Delegates may accordingly be dismissed from their post at any time through recall elections. Soviet democracy forms the basis for the soviet republic system of government.

The anti-Stalinist left encompasses various kinds of Marxist political movements that oppose Joseph Stalin, Stalinism, Neo-Stalinism and the system of governance that Stalin implemented as leader of the Soviet Union between 1924 and 1953. This term also refers to the high ranking political figures and governmental programs that opposed Joseph Stalin and his form of communism, such as Leon Trotsky and other traditional Marxists within the Left Opposition. In Western historiography, Stalin is considered one of the worst and most notorious figures in modern history.

Permanent revolution is the strategy of a revolutionary class pursuing its own interests independently and without compromise or alliance with opposing sections of society. As a term within Marxist theory, it was first coined by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels as early as 1850. Since then different theorists, most notably Leon Trotsky (1879–1940), have used the phrase to refer to different concepts.

Terrorism and Communism: A Reply to Karl Kautsky is a book by Soviet Communist Party leader Leon Trotsky. First published in German in August 1920, the short book was written against a criticism of the Russian Revolution by prominent Marxist Karl Kautsky, who expressed his views on the errors of the Bolsheviks in two successive articles, Dictatorship of the Proletariat, published in 1918 in Vienna, Austria, followed by Terrorism and Communism, published in 1919.

Marxist ethics is a doctrine of morality and ethics that is based on, or derived from, Marxist philosophy. Marx did not directly write about ethical issues and has often been portrayed by subsequent Marxists as a descriptive philosopher rather than a moralist. Despite this, many Marxist theoreticians have sought to develop often conflicting systems of normative ethics based around the principles of historical and dialectical materialism, and Marx's analysis of the capitalist mode of production.

The Permanent Revolution and Results and Prospects is a 1930 book published by Bolshevik-Soviet politician and former head of The Red Army Leon Trotsky. It was first published by the Left Opposition in the Russian language in Germany in 1930. The book was translated into English by John G. Wright and published by New Park Publications in 1931.

The Spanish Revolution, 1931–1939 is a collection of Leon Trotsky's writings about the Spanish Civil War.