Lev Davidovich Bronstein, better known as Leon Trotsky, was a Soviet politician, revolutionary, and political theorist. He was a central figure in the 1905 Revolution, October Revolution, Russian Civil War, and establishment of the Soviet Union. In the early years of Soviet Russia, Trotsky and Vladimir Lenin were widely considered its two most prominent figures, and Trotsky was Lenin's de facto second-in-command in the government from 1917 to 1923. Ideologically a Marxist and a Leninist, Trotsky's thought inspired a school of Marxism known as Trotskyism.

Leninism is a political ideology developed by Russian Marxist revolutionary Vladimir Lenin that proposes the establishment of the dictatorship of the proletariat led by a revolutionary vanguard party as the political prelude to the establishment of communism. Lenin's ideological contributions to the Marxist ideology relate to his theories on the party, imperialism, the state, and revolution. The function of the Leninist vanguard party is to provide the working classes with the political consciousness and revolutionary leadership necessary to depose capitalism.

Trotskyism is the political ideology and branch of Marxism developed by Russian revolutionary and intellectual Leon Trotsky along with some other members of the Left Opposition and the Fourth International. Trotsky described himself as an orthodox Marxist, a revolutionary Marxist, and a Bolshevik–Leninist as well as a follower of Karl Marx, Frederick Engels, Vladimir Lenin, Karl Liebknecht, and Rosa Luxemburg. His relations with Lenin have been a source of intense historical debate. However, on balance, scholarly opinion among a range of prominent historians and political scientists such as E.H. Carr, Isaac Deutscher, Moshe Lewin, Ronald Suny, Richard B. Day and W. Bruce Lincoln was that Lenin’s desired “heir” would have been a collective responsibility in which Trotsky was placed in "an important role and within which Stalin would be dramatically demoted ".

The ten years 1917–1927 saw a radical transformation of the Russian Empire into a socialist state, the Soviet Union. Soviet Russia covers 1917–1922 and Soviet Union covers the years 1922 to 1991. After the Russian Civil War (1917–1923), the Bolsheviks took control. They were dedicated to a version of Marxism developed by Vladimir Lenin. It promised the workers would rise, destroy capitalism, and create a socialist society under the leadership of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. The awkward problem, regarding Marxist revolutionary theory, was the small proletariat, in an overwhelmingly peasant society with limited industry and a very small middle class. Following the February Revolution in 1917 that deposed Nicholas II of Russia, a short-lived provisional government gave way to Bolsheviks in the October Revolution. The Bolshevik Party was renamed the Russian Communist Party (RCP).

Bolshevism is a revolutionary socialist current of Soviet Leninist and later Marxist–Leninist political thought and political regime associated with the formation of a rigidly centralized, cohesive and disciplined party of social revolution, focused on overthrowing the existing capitalist state system, seizing power and establishing the "dictatorship of the proletariat".

The United Opposition was a group formed in the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) in early 1926, when the Left Opposition led by Leon Trotsky, merged with the New Opposition led by Grigory Zinoviev and his close ally Lev Kamenev, in order to strengthen opposition against the Joseph Stalin-led Centre. The United Opposition demanded, among other things, greater freedom of expression within the Communist Party, the dismantling of the New Economic Policy (NEP), more development of heavy industry, and less bureaucracy. The group was effectively destroyed by Stalin's majority by the end of 1927, having had only limited success.

Before the perestroika Soviet era reforms of Gorbachev that promoted a more liberal form of socialism, the formal ideology of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) was Marxism–Leninism, a form of socialism consisting of a centralised command economy with a vanguardist one-party state that aimed to realize the dictatorship of the proletariat. The Soviet Union's ideological commitment to achieving communism included the national communist development of socialism in one country and peaceful coexistence with capitalist countries while engaging in anti-imperialism to defend the international proletariat, combat the predominant prevailing global system of capitalism and promote the goals of Russian Communism. The state ideology of the Soviet Union—and thus Marxism–Leninism—derived and developed from the theories, policies, and political praxis of Marx, Engels, Lenin, and Stalin.

Joseph Stalin started his career as a robber, gangster as well as an influential member and eventually the leader of the Bolshevik faction of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party. He served as the General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from April 3, 1922 until the official abolition of the office during the 19th Party Congress in October 1952 and absolute leader of the USSR from January 21, 1924 until his death on March 5, 1953.

The New Economic Policy (NEP) was an economic policy of the Soviet Union proposed by Vladimir Lenin in 1921 as a temporary expedient. Lenin characterized the NEP in 1922 as an economic system that would include "a free market and capitalism, both subject to state control", while socialized state enterprises would operate on "a profit basis".

Revolutionary socialism is a political philosophy, doctrine, and tradition within socialism that stresses the idea that a social revolution is necessary to bring about structural changes in society. More specifically, it is the view that revolution is a necessary precondition for transitioning from a capitalist to a socialist mode of production. Revolution is not necessarily defined as a violent insurrection; it is defined as a seizure of political power by mass movements of the working class so that the state is directly controlled or abolished by the working class as opposed to the capitalist class and its interests.

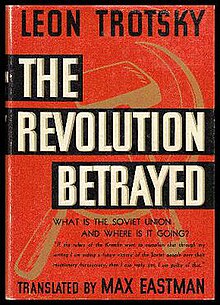

In Trotskyist political theory, a degenerated workers' state is a dictatorship of the proletariat in which the working class' democratic control over the state has given way to control by a bureaucratic clique. The term was developed by Leon Trotsky in The Revolution Betrayed and in other works.

Socialism in one country was a Soviet state policy to strengthen socialism within the country rather than socialism globally. Given the defeats of the 1917–1923 European communist revolutions, Joseph Stalin encouraged the theory of the possibility of constructing socialism in the Soviet Union alone. The theory was eventually adopted as Soviet state policy.

A socialist state, socialist republic, or socialist country, sometimes referred to as a workers' state or workers' republic, is a sovereign state constitutionally dedicated to the establishment of socialism. The term communist state is often used synonymously in the West, specifically when referring to one-party socialist states governed by Marxist–Leninist communist parties, despite these countries being officially socialist states in the process of building socialism and progressing toward a communist society. These countries never describe themselves as communist nor as having implemented a communist society. Additionally, a number of countries that are multi-party capitalist states make references to socialism in their constitutions, in most cases alluding to the building of a socialist society, naming socialism, claiming to be a socialist state, or including the term people's republic or socialist republic in their country's full name, although this does not necessarily reflect the structure and development paths of these countries' political and economic systems. Currently, these countries include Algeria, Bangladesh, Guyana, India, Nepal, Nicaragua, Sri Lanka and Tanzania.

Permanent revolution is the strategy of a revolutionary class pursuing its own interests independently and without compromise or alliance with opposing sections of society. As a term within Marxist theory, it was first coined by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels as early as 1850. Since then different theorists, most notably Leon Trotsky (1879–1940), have used the phrase to refer to different concepts.

Terrorism and Communism: A Reply to Karl Kautsky German: Terrorismus und Kommunismus: Anti-Kautsky; Russian: Терроризм и Коммунизм, Terrorizm i Kommunizm) is a book by Soviet Communist Party leader Leon Trotsky. First published in German in August 1920, the short book was written against a criticism of the Russian Revolution by prominent Marxist Karl Kautsky, who expressed his views on the errors of the Bolsheviks in two successive articles, Dictatorship of the Proletariat, published in 1918 in Vienna, Austria, followed by Terrorism and Communism, published in 1919.

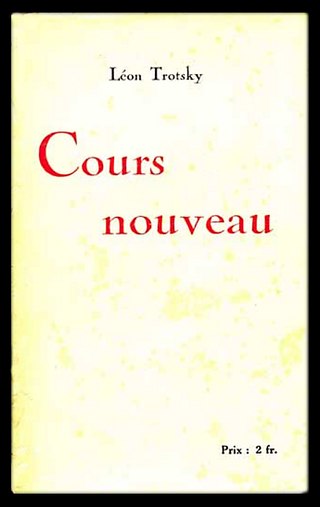

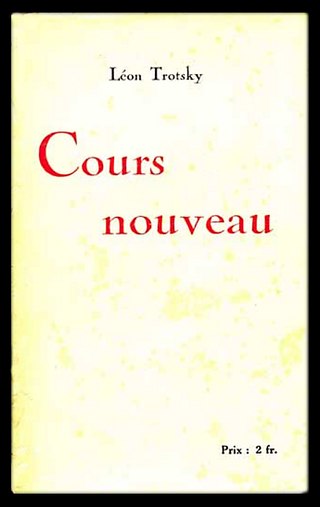

The New Course was a 1924 brochure by political leader Leon Trotsky. Frequently reprinted in various European and Asian language over subsequent decades, the tract is considered a first explicit statement of the Left Opposition within the ruling All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) criticizing a trend towards bureaucracy and an attenuation of worker's control over the political process.

Foundations of Leninism was a 1924 collection made by Joseph Stalin that consisted of nine lectures he delivered at Sverdlov University that year. It was published by the Soviet newspaper, Pravda.

The Permanent Revolution and Results and Prospects is a 1930 book published by Bolshevik-Soviet politician and former head of The Red Army Leon Trotsky. It was first published by the Left Opposition in the Russian language in Germany in 1930. The book was translated into English by John G. Wright and published by New Park Publications in 1931.

Towards Socialism or Capitalism ? is a 1925 economic pamphlet produced by Leon Trotsky which reviewed the industrial development of Soviet Union following the adoption of the New Economic Policy. Trotsky centred his analysis on the statistical figures assembled by GOSPLAN on industrial output. The book examined the prospects for fulfilling industrial targets, socialisation of agriculture and potential dangers facing economic reconstruction such as the political tensions emanating from social stratification.

Their Morals and Ours is a short pamphlet of ethical essays written by Russian revolutionary, Leon Trotsky, in 1938 against various lines of criticisms presented against the perceived actions of Bolsheviks in that "end justifies the means".