Related Research Articles

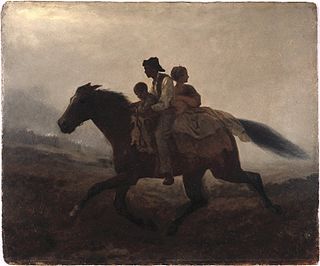

The Underground Railroad was used by freedom seekers from slavery in the United States and was generally an organized network of secret routes and safe houses. Enslaved Africans and African Americans escaped from slavery as early as the 16th century and many of their escapes were unaided, but the network of safe houses operated by agents generally known as the Underground Railroad began to organize in the 1780s among Abolitionist Societies in the North. It ran north and grew steadily until the Emancipation Proclamation was signed in 1863 by President Abraham Lincoln. The escapees sought primarily to escape into free states, and from there to Canada.

Manumission, or enfranchisement, is the act of freeing slaves by their owners. Different approaches to manumission were developed, each specific to the time and place of a particular society. Historian Verene Shepherd states that the most widely used term is gratuitous manumission, "the conferment of freedom on the enslaved by enslavers before the end of the slave system".

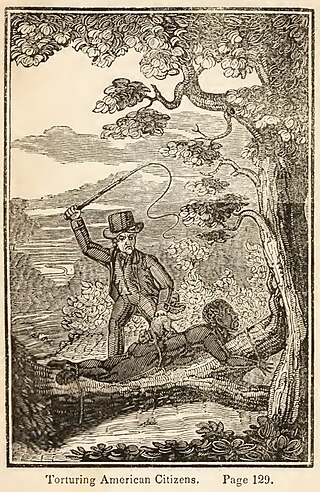

The legal institution of human chattel slavery, comprising the enslavement primarily of Africans and African Americans, was prevalent in the United States of America from its founding in 1776 until 1865, predominantly in the South. Slavery was established throughout European colonization in the Americas. From 1526, during the early colonial period, it was practiced in what became Britain's colonies, including the Thirteen Colonies that formed the United States. Under the law, an enslaved person was treated as property that could be bought, sold, or given away. Slavery lasted in about half of U.S. states until abolition in 1865, and issues concerning slavery seeped into every aspect of national politics, economics, and social custom. In the decades after the end of Reconstruction in 1877, many of slavery's economic and social functions were continued through segregation, sharecropping, and convict leasing.

Angelina Emily Grimké Weld was an American abolitionist, political activist, women's rights advocate, and supporter of the women's suffrage movement. At one point she was the best known, or "most notorious," woman in the country. She and her sister Sarah Moore Grimké were considered the only notable examples of white Southern women abolitionists. The sisters lived together as adults, while Angelina was the wife of abolitionist leader Theodore Dwight Weld.

Theodore Parker was an American transcendentalist and reforming minister of the Unitarian church. A reformer and abolitionist, his words and popular quotations would later inspire speeches by Abraham Lincoln and Martin Luther King Jr.

In the United States, fugitive slaves or runaway slaves were terms used in the 18th and 19th centuries to describe people who fled slavery. The term also refers to the federal Fugitive Slave Acts of 1793 and 1850. Such people are also called freedom seekers to avoid implying that the enslaved person had committed a crime and that the slaveholder was the injured party.

James Henry Hammond was an American attorney, politician, and planter. He served as a United States representative from 1835 to 1836, the 60th Governor of South Carolina from 1842 to 1844, and a United States senator from 1857 to 1860. An enslaver, Hammond was one of the most ardent supporters of slavery in the years before the American Civil War.

The Slave Power, or Slavocracy, referred to the perceived political power held by American slaveowners in the federal government of the United States during the Antebellum period. Antislavery campaigners charged that this small group of wealthy slaveholders had seized political control of their states and were trying to take over the federal government illegitimately to expand and protect slavery. The claim was later used by the Republican Party that formed in 1854–55 to oppose the expansion of slavery.

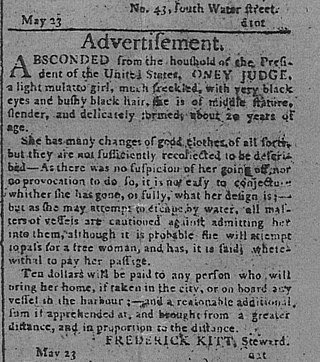

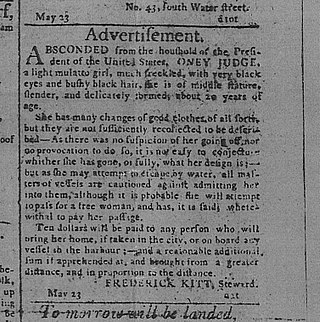

Ona "Oney" Judge Staines was a woman enslaved by the Washington family, first at the family's plantation at Mount Vernon and later, after George Washington became president, at the President's House in Philadelphia, then the nation's capital city. In her early twenties, Judge absconded, becoming a fugitive slave, after learning that Martha Washington had intended to transfer her enslavement to her granddaughter, known to have a horrible temper. Judge fled to New Hampshire, where she married, had children, and converted to Christianity. Though Judge was never formally freed, the Washington family ultimately stopped pressing her to return to enslavement in Virginia after George Washington's death.

Proslavery is support for slavery. It is sometimes found in the thought of ancient philosophers, religious texts, and in American and British writings especially before the American Civil War but also later through the 20th century. Arguments in favor of slavery include deference to the Bible and thus to God, some people being natural slaves in need of supervision, slaves often being better off than the poorest non-slaves, practical social benefit for the society as a whole, and slavery being a time-proven practice by multiple great civilizations.

The history of slavery in Texas began slowly at first during the first few phases in Texas' history. Texas was a colonial territory, then part of Mexico, later Republic in 1836, and U.S. state in 1845. The use of slavery expanded in the mid-nineteenth century as White American settlers, primarily from the Southeastern United States, crossed the Sabine River and brought enslaved people with them. Slavery was present in Spanish America and Mexico prior to the arrival of American settlers, but it was not highly developed, and the Spanish did not rely on it for labor during their years in Spanish Texas.

When the Dutch and Swedes established colonies in the Delaware Valley of what is now Pennsylvania, in North America, they quickly imported enslaved Africans for labor; the Dutch also transported them south from their colony of New Netherland. Enslavement was documented in this area as early as 1639. William Penn and the colonists who settled in Pennsylvania tolerated slavery. Still, the English Quakers and later German immigrants were among the first to speak out against it. Many colonial Methodists and Baptists also opposed it on religious grounds. During the Great Awakening of the late 18th century, their preachers urged slaveholders to free their slaves. High British tariffs in the 18th century discouraged the importation of additional slaves, and encouraged the use of white indentured servants and free labor.

The President's House in Philadelphia was the third U.S. Presidential Mansion. George Washington occupied it from November 27, 1790, to March 10, 1797, and John Adams occupied it from March 21, 1797, to May 30, 1800.

Thomas Jefferson, the third president of the United States, owned more than 600 slaves during his adult life. Jefferson freed two slaves while he lived, and five others were freed after his death, including two of his children from his relationship with his slave Sally Hemings. His other two children with Hemings were allowed to escape without pursuit. After his death, the rest of the slaves were sold to pay off his estate's debts.

An Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery, passed by the Fifth Pennsylvania General Assembly on 1 March 1780, prescribed an end for slavery in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania in the United States. It was the first slavery abolition act in the course of human history to be adopted by an elected body.

Slavery in Maryland lasted over 200 years, from its beginnings in 1642 when the first Africans were brought as slaves to St. Mary's City, to its end after the Civil War. While Maryland developed similarly to neighboring Virginia, slavery declined in Maryland as an institution earlier, and it had the largest free black population by 1860 of any state. The early settlements and population centers of the province tended to cluster around the rivers and other waterways that empty into the Chesapeake Bay. Maryland planters cultivated tobacco as the chief commodity crop, as the market for cash crops was strong in Europe. Tobacco was labor-intensive in both cultivation and processing, and planters struggled to manage workers as tobacco prices declined in the late 17th century, even as farms became larger and more efficient. At first, indentured servants from England supplied much of the necessary labor but, as England's economy improved, fewer came to the colonies. Maryland colonists turned to importing indentured and enslaved Africans to satisfy the labor demand.

Slavery in Virginia began with the capture and enslavement of Native Americans during the early days of the English Colony of Virginia and through the late eighteenth century. They primarily worked in tobacco fields. Africans were first brought to colonial Virginia in 1619, when 20 Africans from present-day Angola arrived in Virginia aboard the ship The White Lion.

Freedom suits were lawsuits in the Thirteen Colonies and the United States filed by slaves against slaveholders to assert claims to freedom, often based on descent from a free maternal ancestor, or time held as a resident in a free state or territory.

Slavery as a positive good in the United States was the prevailing view of Southern politicians and intellectuals just before the American Civil War, as opposed to seeing it as a crime against humanity or a necessary evil. They defended the legal enslavement of people for their labor as a benevolent, paternalistic institution with social and economic benefits, an important bulwark of civilization, and a divine institution similar or superior to the free labor in the North.

Polly Strong was an enslaved woman in the Northwest Territory, in present-day Indiana. She was born after the Northwest Ordinance prohibited slavery. Slavery was prohibited by the Constitution of Indiana in 1816. Two years later, Strong's mother Jenny and attorney Moses Tabbs asked for a writ of habeas corpus for Polly and her brother James in 1818. Judge Thomas H. Blake produced indentures, Polly for 12 more years and James for four more years of servitude. The case was dismissed in 1819.

References

- ↑ Parker, Theodore. To a Southern Slaveholder.

- ↑ ushistory.org. "The Southern Argument for Slavery [ushistory.org]". www.ushistory.org. Retrieved 2016-11-21.