Related Research Articles

The Kingdom of the Iberians was a medieval Georgian monarchy under the Bagrationi dynasty which emerged circa 888 AD, succeeding the Principality of Iberia, in historical region of Tao-Klarjeti, or upper Iberia in north-eastern Turkey as well parts of modern southwestern Georgia, that stretched from the Iberian gates in the south and to the Lesser Caucasus in the north.

Ashot I the Great was a presiding prince of Iberia, first of the Bagratid family to have attained to this office c. 813. From his base in Tao-Klarjeti, he fought to enlarge the Bagratid territories and sought the Byzantine protectorate against the Arab Muslim encroachment until being murdered c. 826. Ashot is also known as Ashot I Kouropalates for the Byzantine title of kouropalates that he bore. A patron of Christian culture and a friend of the church, he has been canonized by the Georgian Orthodox Church.

Tsanareti was a historic district (Khevi) in the early medieval Caucasus, lying chiefly in what is now the northeastern corner in Georgia’s region of Mtskheta-Mtianeti.

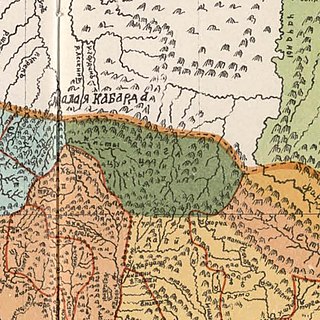

The Dvals were a ethnographic group of Georgians. Their lands lying on both sides of the central Greater Caucasus mountains, somewhere between the Darial and Mamison gorges. This historic territory mostly covers the north of Kartli, parts of the Racha and Khevi regions in Georgia and south of Ossetia in Russia.

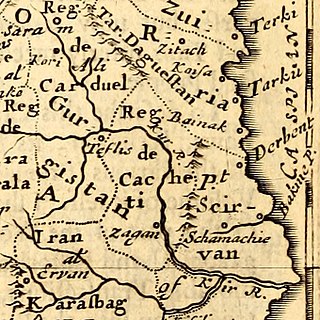

The Emirate of Tbilisi was a Muslim emirate in Transcaucasia. The Emirs of Tbilisi ruled over the parts of today's eastern Georgia from their base in the city of Tbilisi, from 736 to 1080. Established by the Arabs during their rule of Georgian lands, the emirate was an important outpost of the Muslim rule in the Caucasus until recaptured by the Georgians under King David IV in 1122.

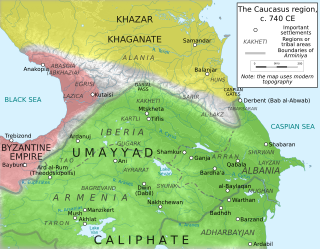

The Arab–Khazar wars were a series of conflicts fought between the Khazar Khaganate and successive Arab caliphates in the Caucasus region from c. 642 to 799 CE. Smaller native principalities were also involved in the conflict as vassals of the two empires. Historians usually distinguish two major periods of conflict, the First Arab–Khazar War and Second Arab–Khazar War ; the wars also involved sporadic raids and isolated clashes from the mid-seventh century to the end of the eighth century.

Arminiya, also known as the Ostikanate of Arminiya or the Emirate of Armenia, was a political and geographic designation given by the Muslim Arabs to the lands of Greater Armenia, Caucasian Iberia, and Caucasian Albania, following their conquest of these regions in the 7th century. Though the caliphs initially permitted an Armenian prince to represent the province of Arminiya in exchange for tribute and the Armenians' loyalty during times of war, Caliph Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan introduced direct Arab rule of the region, headed by an ostikan with his capital in Dvin. According to the historian Stephen H. Rapp in the third edition of the Encyclopaedia of Islam:

Early Arabs followed Sāsānian, Parthian Arsacid, and ultimately Achaemenid practice by organising most of southern Caucasia into a large regional zone called Armīniya.

Sahl Smbatean Eṙanshahik was an Armenian prince of Arran and Shaki who played a considerable role in the history of the eastern Caucasus during the 9th century and was the ancestor of the House of Khachen established in 821.

The Shirvanshahs were the rulers of Shirvan from 861 to 1538. The first ruling line were the Yazidids, an originally Arab and later Persianized dynasty, who became known as the Kasranids. The second ruling line were the Darbandi, distant relatives of the Yazidids/Kasranids.

The Durdzuks, also known as Dzurdzuks, was a medieval exonym of the 9th-18th centuries used mainly in Georgian, Arabic, but also Armenian sources in reference to the Vainakh peoples.

Muhammad ibn Khalid ibn Yazid al-Shaybani was an Arab general and governor for the Abbasid Caliphate, active in the Caliphate's Caucasian provinces in the 9th century.

Lashkar Haytham ibn Khalid was the first Shirvanshah, or independent ruler of Shirvan, renouncing the suzerainty of the Abbasid Caliphate in 861 after the Anarchy at Samarra and beginning the rule of the Mazyadid or Yazidid dynasty.

Arab rule in Georgia, natively known as Araboba, refers to the period in the history of Georgia when parts of what is now Georgia came under Arab rule, starting with the first Arab incursions in the mid-7th century until the final defeat of the Emirate of Tbilisi at the hands of King David IV in 1122. Compared with other regions which endured Muslim conquests, Georgia's culture, and even political structure was not much affected by the Arab presence, as the people kept their faith, the nobles their fiefdoms, and the foreign rulers mostly insisted on the payment of tribute, which they could not always enforce. Still, repeated invasions and military campaigns by the Arabs devastated Georgia on many occasions, and the Caliphs retained suzerainty over significant parts of the country and exerted influence over the internal power dynamics during most of the period.

Sajid invasion of Georgia was the final attempt to establish Muslim hegemony in the South Caucasus before the Seljuk invasions. Yusuf Ibn Abi'l-Saj, a Sajid emir, whom Georgians knew as Abul-Kasim, invaded Georgian lands in 914, with the purpose to strengthen gradually weakening Arab power and Muslim hold on Georgian principalities. He first reached Tbilisi, then turned towards Kakheti and besieged the fortresses of Ujarma and Botchorma. Later, he made peace with Kvirike, chorepiscopus (ruler) of Kakheti and returned control of Ujarma to him. After this, he marched his forces to Kartli and laid waste to it. Georgians themselves destroyed the fortifications of Uplistsikhe, so it wouldn't fall to the hands of the enemy. The Muslim forces then raided Meskheti as well, but were unable to take the Tmogvi fortress and retreated. On the way they besieged Q'ueli fortress and took it despite stiff resistance. Muslims captured the military commander of the castle, Gobron, and put him to death. He was later canonized by Georgian Orthodox Church. Despite his military successes Abu l'Kasim was unable to attain his goal. He was forced to finally retreat from Georgian lands because of stubborn resistance by people whose lands he was so eager to ravage and subject.

Ishaq b. Isma'il b. Shuab al-Tiflisi , also known as Sahak in Georgian sources, was the emir of Tbilisi between 833 and 853. He was married to a daughter of king of Sarir and followed his uncle Ali on the throne.

Zagem or Bazari was a town in the southeast Caucasus, in the eastern Georgian kingdom of Kakheti. It flourished from the 15th to the 17th century as a vibrant commercial and artisanal centre. In the 1550s, it became a dependency of the Karabakh–Ganja province of Safavid Iran. The fortunes of the town were reversed by Safavid military actions in the area in 1615. By the 1720s, the town had been reduced to an insignificant hamlet. The settlement was located in what is now the Zaqatala District of Azerbaijan, but no evidence of the town remains at the site. The toponym Zagem is found exclusively in non-Georgian sources; Georgians knew it as Bazari, meaning "bazaar".

The Kingdom of Kakheti-Hereti was an early medieval Georgian monarchy in eastern Georgia, centered at the province of Kakheti, with its capital first at Telavi. It emerged in c. 1014 AD, under the leadership of energetic ruler of principality of Kakheti, Kvirike III the Great that finally defeated the ruler of Hereti and crowned himself as a king of the unified realms of Kakheti and Hereti. From this time on, until 1104, the kingdom was an independent and separated state from the united Kingdom of Georgia. The kingdom included territories from riv. Ksani to Alijanchay river and from Didoeti to southwards along the river of Mtkvari.

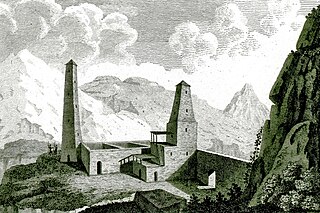

Dzheyrakh - is a village and administrative center of Dzheyrakhsky District, in the Republic of Ingushetia, Russia.

Sultan-Murza or Saltan-Murza was an Ingush feudal lord who controlled the Darial Gorge and the village located in it, Lars. In 1589, he swore allegiance to the Russian Tsar Feodor I as part of the Georgian embassy, therefore becoming subordinated to the Tsardom of Russia.

Ghalghay is the self-name (endonym) of the Ingush people.

References

- ↑ Volkova 1973, pp. 125–126.

- ↑ Volkova 1973, pp. 126–127.

- 1 2 Minorsky 1953, p. 506 (note 3).

- ↑ Rapp 2003, p. 399.

- ↑ Volkova 1973, p. 125.

- 1 2 3 Shaginyan 2008a, p. 82.

- ↑ Shaginyan 2008a, p. 87 (citation 27).

- ↑ Shaginyan 2008a, p. 78.

- ↑ Shaginyan 2008a, p. 85.

- ↑ Minorsky 1958, p. 19.

- ↑ Shaginyan 2008b, p. 112.

- 1 2 3 Vacca 2017, pp. 85–86.

- ↑ Minorsky 1953, p. 512.

- ↑ Minorsky 1958, p. 110 (note 2).

- 1 2 3 Novoseltsev 1990, p. 107.

- ↑ Vacca 2017, p. 85.

- 1 2 Tuallagov 2018, p. 26.

- ↑ Novoseltsev 1990, p. 107 (see the citation 94 on p. 156).

- ↑ "batsav | prof. topchishvili on the batsbi". www.batsav.com. Retrieved 2024-02-16.

- ↑ SHIOLASHVILI, PKHALADZE, AKHALADZE, BURDULI, KISTAURI. ETUDES FROM TRUSSO'S PAST (in English and Georgian). pp. http://sciencejournals.ge/index.php/HAE/article/download/378/335/.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ ITONISHVILI. "დვალეთის ისტორიის საკითხები მრუდე სარკეში" (PDF).

- ↑ Chikobava, Akaki. "საქართველოს ისტორიის ნარკვევები. ტომი II. საქართველოს IV-X საუკუნეებში. თბილისი. 1973".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Japaridze, Anania (2022). ალბანეთის საკათალიკოსო და საქართველოს ეკლესიის: იურისდიქცია კახეთსა და ჰერეთში [Catholicos Church of Albania and Church of Georgia: Jurisdiction in Kakheti and Hereti](PDF) (in Georgian). pp. 8–9.

- ↑ Tsulaya 1986, p. 26 (citation 130).

- 1 2 3 Volkova 1973, p. 126.

- ↑ Volkova 1973, p. 127.

- ↑ Dunlop 1960.

- ↑ Vacca 2017, pp. 86–87.

- ↑ Rapp 2003, p. 398.

- ↑ Minorsky 1958, p. 162 (note 1).