Related Research Articles

The gens Claudia, sometimes written Clodia, was one of the most prominent patrician houses at ancient Rome. The gens traced its origin to the earliest days of the Roman Republic. The first of the Claudii to obtain the consulship was Appius Claudius Sabinus Regillensis, in 495 BC, and from that time its members frequently held the highest offices of the state, both under the Republic and in imperial times.

The gens Sulpicia was one of the most ancient patrician families at ancient Rome, and produced a succession of distinguished men, from the foundation of the Republic to the imperial period. The first member of the gens who obtained the consulship was Servius Sulpicius Camerinus Cornutus, in 500 BC, only nine years after the expulsion of the Tarquins, and the last of the name who appears on the consular list was Sextus Sulpicius Tertullus in AD 158. Although originally patrician, the family also possessed plebeian members, some of whom may have been descended from freedmen of the gens.

The gens Licinia was a celebrated plebeian family at ancient Rome, which appears from the earliest days of the Republic until imperial times, and which eventually obtained the imperial dignity. The first of the gens to obtain the consulship was Gaius Licinius Calvus Stolo, who, as tribune of the plebs from 376 to 367 BC, prevented the election of any of the annual magistrates, until the patricians acquiesced to the passage of the lex Licinia Sextia, or Licinian Rogations. This law, named for Licinius and his colleague, Lucius Sextius, opened the consulship for the first time to the plebeians. Licinius himself was subsequently elected consul in 364 and 361 BC, and from this time, the Licinii became one of the most illustrious gentes in the Republic.

The gens Scribonia was a plebeian family of ancient Rome. Members of this gens first appear in history at the time of the Second Punic War, but the first of the Scribonii to obtain the consulship was Gaius Scribonius Curio in 76 BC.

The gens Marcia, occasionally written Martia, was one of the oldest and noblest houses at ancient Rome. They claimed descent from the second and fourth Roman Kings, and the first of the Marcii appearing in the history of the Republic would seem to have been patrician; but all of the families of the Marcii known in the later Republic were plebeian. The first to obtain the consulship was Gaius Marcius Rutilus in 357 BC, only a few years after the passage of the lex Licinia Sextia opened this office to the plebeians.

The gens Terentia was a plebeian family at ancient Rome. Dionysius mentions a Gaius Terentius Arsa, tribune of the plebs in 462 BC, but Livy calls him Terentilius, and from inscriptions this would seem to be a separate gens. No other Terentii appear in history until the time of the Second Punic War. Gaius Terentius Varro, one of the Roman commanders at the Battle of Cannae in 216 BC, was the first to hold the consulship. Members of this family are found as late as the third century AD.

The gens Minucia was an ancient Roman family, which flourished from the earliest days of the Republic until imperial times. The gens was apparently of patrician origin, but was better known by its plebeian branches. The first of the Minucii to hold the consulship was Marcus Minucius Augurinus, elected consul in 497 BC.

The gens Pinaria was one of the most ancient patrician families at Rome. According to tradition, the gens originated long before the founding of the city. The Pinarii are mentioned under the kings, and members of this gens attained the highest offices of the Roman state soon after the establishment of the Republic, beginning with Publius Pinarius Mamercinus Rufus, consul in 489 BC.

The gens Lollia was a plebeian family at Rome. Members of the gens do not appear at Rome until the last century of the Republic. The first of the family to obtain the consulship was Marcus Lollius, in 21 BC.

The gens Postumia was a noble patrician family at ancient Rome. Throughout the history of the Republic, the Postumii frequently occupied the chief magistracies of the Roman state, beginning with Publius Postumius Tubertus, consul in 505 BC, the fifth year of the Republic. Although like much of the old Roman aristocracy, the Postumii faded for a time into obscurity under the Empire, individuals bearing the name of Postumius again filled a number of important offices from the second century AD to the end of the Western Empire.

The gens Antistia, sometimes written Antestia on coins, was a plebeian family at ancient Rome. The first of the gens to achieve prominence was Sextus Antistius, tribune of the plebs in 422 BC.

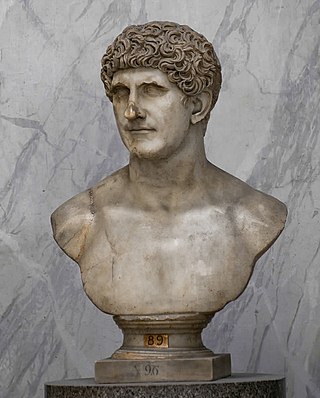

The gens Antonia was a Roman family of great antiquity, with both patrician and plebeian branches. The first of the gens to achieve prominence was Titus Antonius Merenda, one of the second group of Decemviri called, in 450 BC, to help draft what became the Law of the Twelve Tables. The most prominent member of the gens was Marcus Antonius.

The gens Caecilia was a plebeian family at ancient Rome. Members of this gens are mentioned in history as early as the fifth century BC, but the first of the Caecilii who obtained the consulship was Lucius Caecilius Metellus Denter, in 284 BC. The Caecilii Metelli were one of the most powerful families of the late Republic, from the decades before the First Punic War down to the time of Augustus.

The gens Servilia was a patrician family at ancient Rome. The gens was celebrated during the early ages of the Republic, and the names of few gentes appear more frequently at this period in the consular Fasti. It continued to produce men of influence in the state down to the latest times of the Republic, and even in the imperial period. The first member of the gens who obtained the consulship was Publius Servilius Priscus Structus in 495 BC, and the last of the name who appears in the consular Fasti is Quintus Servilius Silanus, in AD 189, thus occupying a prominent position in the Roman state for nearly seven hundred years.

The gens Canuleia was a minor plebeian family at ancient Rome. Although members of this gens are known throughout the period of the Republic, and were of senatorial rank, none of them ever obtained the consulship. However, the Canuleii furnished the Republic with several tribunes of the plebs.

The gens Cosconia was a plebeian family at Rome. Members of this gens are first mentioned in the Second Punic War, but none ever obtained the honours of the consulship; the first who held a curule office was Marcus Cosconius, praetor in 135 BC.

The gens Furnia was a plebeian family at ancient Rome. The Furnian gens was of great antiquity, dating to the first century of the Republic; Gaius Furnius was tribune of the plebs in 445 BC. However, no member of the family achieved prominence again for nearly four hundred years.

The gens Herennia was a plebeian family at ancient Rome. Members of this gens are first mentioned among the Italian nobility during the Samnite Wars, and they appear in the Roman consular list beginning in 93 BC. In Imperial times they held a number of provincial offices and military commands. The empress Herennia Etruscilla was a descendant of this gens.

The gens Mummia was a plebeian family at Rome. Members of this gens are first mentioned after the Second Punic War, and within a generation, Lucius Mummius Achaicus became the first of the family to obtain the consulship. Although they were never numerous, Mummii continued to fill the highest offices of the state through the third century AD.

The gens Oppia was an ancient Roman family, known from the first century of the Republic down to imperial times. The gens may originally have been patrician, as they supplied priestesses to the College of Vestals at a very early date, but all of the Oppii known to history were plebeians. None of them obtained the consulship until imperial times.

References

- 1 2 3 Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography & Mythology, vol. III, p. 1183 ("Tullia Gens").

- ↑ Chase, pp. 145, 146.

- ↑ Cicero, Brutus, 62, Tusculanae Quaestiones, i. 16.

- ↑ Livy, i. 30.

- ↑ Wiseman, "Legendary Genealogies", p. 158.

- ↑ Chase, p. 110.

- ↑ Chase, p. 113.

- ↑ Plutarch, The Life of Cicero, 1.

- ↑ Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, vol. I, pp. 707, 708 ("Cicero").

- ↑ Livy, i. 39.

- ↑ Dionysius, iv. 1, 2.

- ↑ Ovid, Fasti, vi. 573 ff, 625 ff.

- ↑ Valerius Maximus, i. 8 § 11.

- ↑ Dionysius, iv. 1–40.

- ↑ Cicero, De Republica, ii. 21, 22.

- ↑ Livy, i. 39–48.

- ↑ Zonaras, vii. 9.

- ↑ Niebuhr, History of Rome, vol. i, pp. 249, 398 ff.

- ↑ Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, vol. III, pp. 1184–1190 ("Servius Tullius").

- ↑ Valerius Maximus, i. 1. § 13.

- ↑ Dionysius, iv. 62.

- ↑ Livy, ii. 19.

- ↑ Dionysius, v. 52–57.

- ↑ Zonaras, vii. 13.

- ↑ Cicero, Brutus, 16.

- 1 2 Broughton, vol. I, p. 21 (and note 1).

- ↑ Festus, 180 L.

- ↑ Valerius Maximus, vi. 3. § 2.

- ↑ Livy, ii. 35–40.

- ↑ Dionysius, viii. 1–5, 10–13.

- ↑ Plutarch, "The Life of Coriolanus", 22, 23, 26–28, 31, 39.

- ↑ Niebuhr, History of Rome, vol. ii, note. 217.

- ↑ Livy, vii. 13–16.

- ↑ Cicero, De Legibus, ii. 1, iii. 16, De Oratore, ii. 66.

- ↑ Cicero, De Legibus, ii. 1, De Oratore, ii. 1, De Officiis, iii. 19, Epistulae ad Atticum, i. 6.

- ↑ Cicero, De Oratore, ii. 1.

- ↑ Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, vol. I, pp. 708–746.

- ↑ Cicero, De Finibus, v. 1, In Verrem, iv. 11, 61, 64, 65, Epistulae ad Atticum, i. 5.

- ↑ Treggiari. 25 (2007)

- ↑ Orelli, Onomasticon Tullianum, vol. ii., pp. 596, 597.

- ↑ Drumann, Geschichte Roms, vol. vi, pp. 696 ff.

- ↑ Crawford, Roman Republican Coinage, p. 297.

- ↑ Cicero, De Lege Agraria, ii. 14.

- ↑ Gellius, xv. 28.

- ↑ Appian, Bellum Civile, i. 100.

- ↑ Drumann, Geschichte Roms, vol. v, pp. 258 ff.

- ↑ Cicero, In Verrem, iii. 71.

- ↑ Cicero, Epistulae ad Atticum, v. 4, 11, 14, 21, Epistulae ad Familiares, xv. 14. § 8.

- ↑ Gellius, xiii. 9.

- ↑ Cicero, Epistulae ad Familiares, liber xvi, Epistulae ad Atticum, iv. 6, vi. 7, vii. 2, 3, 5, xiii. 7, xvi. 5.

- ↑ Martial, Epigrammata, xiv. 202.

- ↑ Manilius, Astronomica, iv. 197.

- ↑ Seneca the Younger, Epistulae, 90.

- ↑ Plutarch, "The Life of Cicero", 41, 49.

- ↑ Drumann, Geschichte Roms, vol. vi, p. 409.

- ↑ Pliny the Elder, xxxi. 2.

- ↑ Burmann, Anthologia Latina, vol. i, p. 340.

- ↑ Fabricius, Bibliotheca Graeca, vol. iv, p. 493.

- ↑ Analecta Veterum Poetarum Graecorum, vol. ii, p. 102.

- ↑ Anthologia Graeca, vol. ii, p. 90, vol. xiii, p. 907.

- ↑ Caesar, De Bello Hispaniensis, 17, 18.

- ↑ Pliny the Elder, index to Historia Naturalis, xx.

- ↑ Caelius Aurelianus, De Morbis Acutis, iii. 16, p. 233.

- ↑ Fabricius, Bibliotheca Graeca, vol. xiii, p. 101 (ed. vet).

- ↑ Cicero, Epistulae ad Atticum, xii. 52, 53, xiv. 16, 17, xv. 26, 29.

- ↑ Tacitus, Annales, xv. 50, 56, 70.

- ↑ Tacitus, Historiae, iii. 79.

- ↑ Tacitus, Historiae, iv. 69–74, 85.

- ↑ Eck & Weiß "Hadrianische Konsuln", p. 482.

- ↑ Analecta Veterum, vol. ii, p. 279.

- ↑ Anthologia Graeca, vol. ii, p. 254, vol. xiii, p. 897.

- ↑ Fabricius, Bibliotheca Graeca, vol. iv, p. 498.