The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was a group of English painters, poets, and art critics, founded in 1848 by William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William Michael Rossetti, James Collinson, Frederic George Stephens and Thomas Woolner who formed a seven-member "Brotherhood" partly modelled on the Nazarene movement. The Brotherhood was only ever a loose association and their principles were shared by other artists of the time, including Ford Madox Brown, Arthur Hughes and Marie Spartali Stillman. Later followers of the principles of the Brotherhood included Edward Burne-Jones, William Morris and John William Waterhouse.

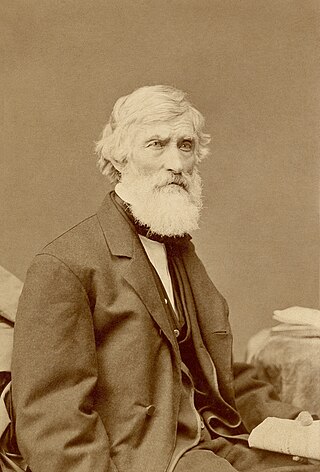

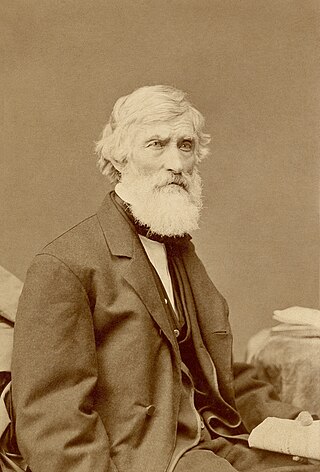

Frederic Edwin Church was an American landscape painter born in Hartford, Connecticut. He was a central figure in the Hudson River School of American landscape painters, best known for painting large landscapes, often depicting mountains, waterfalls, and sunsets. Church's paintings put an emphasis on realistic detail, dramatic light, and panoramic views. He debuted some of his major works in single-painting exhibitions to a paying and often enthralled audience in New York City. In his prime, he was one of the most famous painters in the United States.

The Hudson River School was a mid-19th-century American art movement embodied by a group of landscape painters whose aesthetic vision was influenced by Romanticism. Early on, the paintings typically depicted the Hudson River Valley and the surrounding area, including the Catskill, Adirondack, and White Mountains.

Thomas Cole was an English-born American artist and the founder of the Hudson River School art movement. Cole is widely regarded as the first significant American landscape painter. He was known for his romantic landscape and history paintings. Influenced by European painters, but with a strong American sensibility, he was prolific throughout his career and worked primarily with oil on canvas. His paintings are typically allegoric and often depict small figures or structures set against moody and evocative natural landscapes. They are usually escapist, framing the New World as a natural eden contrasting with the smog-filled cityscapes of Industrial Revolution-era Britain, in which he grew up. His works, often seen as conservative, criticize the contemporary trends of industrialism, urbanism, and westward expansion.

Asher Brown Durand was an American painter of the Hudson River School.

John Frederick Kensett was an American landscape painter and engraver born in Cheshire, Connecticut. He was a member of the second generation of the Hudson River School of artists. Kensett's signature works are landscape paintings of New England and New York State, whose clear light and serene surfaces celebrate transcendental qualities of nature, and are associated with Luminism. Kensett's early work owed much to the influence of Thomas Cole, but was from the outset distinguished by a preference for cooler colors and an interest in less dramatic topography, favoring restraint in both palette and composition. The work of Kensett's maturity features tranquil scenery depicted with a spare geometry, culminating in series of paintings in which coastal promontories are balanced against glass-smooth water. He was a founder of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Jervis McEntee was an American painter of the Hudson River School. He is a lesser-known figure of the 19th-century American art world, but was a close friend and traveling companion of several of the important Hudson River School artists. Aside from his paintings, McEntee's unpublished journals, written from 1872 to 1890, are an enduring legacy, documenting the life of a New York painter during and after the Gilded Age.

Fitz Henry Lane was an American painter and printmaker of a style that would later be called Luminism, for its use of pervasive light.

Sanford Robinson Gifford was an American landscape painter and a leading member of the second generation of Hudson River School artists. A highly-regarded practitioner of Luminism, his work was noted for its emphasis on light and soft atmospheric effects.

Luminism is a style of American landscape painting of the 1850s to 1870s, characterized by effects of light in a landscape, through the use of aerial perspective and the concealing of visible brushstrokes. Luminist landscapes emphasize tranquility, often depicting calm, reflective water and a soft, hazy sky. Artists who were most central to the development of the luminist style include Fitz Henry Lane, Martin Johnson Heade, Sanford Gifford, and John F. Kensett. Painters with a less clear affiliation include Frederic Edwin Church, Jasper Cropsey, Albert Bierstadt, Worthington Whittredge, Raymond Dabb Yelland, Alfred Thompson Bricher, James Augustus Suydam, and David Johnson. Some precursor artists are George Harvey and Robert Salmon. Joseph Rusling Meeker also worked in the style.

Olana State Historic Site is a historic house museum and landscape in Greenport, New York, near the city of Hudson. The estate was home to Frederic Edwin Church (1826–1900), one of the major figures in the Hudson River School of landscape painting. The centerpiece of Olana is an eclectic villa which overlooks parkland and a working farm designed by the artist. The residence has a wide view of the Hudson River Valley, the Catskill Mountains and the Taconic Range. Church and his wife Isabel (1836–1899) named their estate after a fortress-treasure house in ancient Greater Persia, which also overlooked a river valley.

David Johnson was an American painter, a member of the second generation of Hudson River School painters.

The Heart of the Andes is a large oil-on-canvas landscape painting by the American artist Frederic Edwin Church (1826–1900). It depicts an idealized landscape in the South American Andes, where Church traveled on two occasions. Measuring more than five feet high and almost ten feet wide, its New York City exhibition in 1859 was a sensation, establishing Church as the foremost landscape painter in the United States.

William Stanley Haseltine was an American painter and draftsman who was associated with the Düsseldorf school of painting, the Hudson River School and Luminism.

Edmund Darch Lewis was an American landscape painter known for his prolific style and marine oils and watercolors. Lewis was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in a well-to-do family. He started training at age 15 with German-born Paul Weber (1823–1916) of the Hudson River School. At age 19 he exhibited at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, and was elected an Associate of the Academy at age 24.

The Icebergs is an 1861 oil painting by the American landscape artist Frederic Edwin Church. It was inspired by his 1859 voyage to the North Atlantic around Newfoundland and Labrador. Considered one of Church's "Great Pictures"—measuring 1.64 by 2.85 metres —the painting depicts one or more icebergs in the afternoon light of the Arctic. It was first displayed in New York City in 1861, where visitors paid 25 cents' admittance to the one-painting show. Similar exhibitions in Boston and London followed. The unconventional landscape of ice, water, and sky generally drew praise, but the American Civil War, which began the same year, lessened critical and popular interest in New York City's cultural events.

Niagara is an oil painting produced in 1857 by the American artist Frederic Edwin Church. Niagara was his most important work at the time, and confirmed his reputation as the premier American landscape painter of the time. In his history of Niagara Falls, Pierre Berton writes, "Of the hundreds of paintings made of Niagara, before Church and after him, this is by common consent the greatest."

The Andes of Ecuador is an 1855 oil painting by Frederic Edwin Church, the premier American landscape painter of the time. It is the most significant result of his 1853 trip to South America, where he would travel again in 1857. It is Church's first major painting, his largest work at the time, and "an early masterpiece of Luminism", according to the Reynolda House Museum of American Art in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, which holds the painting.

Cotopaxi is an 1862 oil painting by American artist Frederic Edwin Church, a member of the Hudson River School. The painting depicts Cotopaxi, an active volcano that is also the second highest peak in modern-day Ecuador, spewing smoke and ash across a colorful sunrise. The work was commissioned by well-known philanthropist and collector James Lenox and was first exhibited in New York City in 1863. Cotopaxi was met with great acclaim, seen by some as a "parable" of the Civil War, then raging in the American South, with its casting of light against darkness in a vast tropical landscape. Church first depicted Cotopaxi beginning in 1853 during his first of several travels to South America, forming a series of at least 10 paintings on the subject during his lifetime. Cotopaxi has been called by some art historians the "apex" of the Cotopaxi series or Church's "ultimate interpretation" of the eponymous volcano.

Mountain Landscape, previously known as Sunset—West Rock, New Haven, is an 1849 landscape painting by American artist Frederic Edwin Church of the Hudson River School, completed during his early period. The work depicts a mountain landscape with a lake and a small farm in the Northeastern United States based on Church's travels through the state of Vermont. The painting was originally part of the Nickerson art collection but was later donated to Valparaiso University as part of the Sloan bequest in 1953 and exhibited at the Brauer Museum of Art. In 2023, the university proposed selling the painting as an asset to fund dormitory renovations, leading to a contentious debate about the ethics of deaccessioning artwork.