Individualist anarchism is the branch of anarchism that emphasizes the individual and their will over external determinants such as groups, society, traditions, and ideological systems. Although usually contrasted with social anarchism, both individualist and social anarchism have influenced each other. Some anarcho-capitalists claim anarcho-capitalism is part of the individualist anarchist tradition, while others disagree and claim individualist anarchism is only part of the socialist movement and part of the libertarian socialist tradition. Economically, while European individualist anarchists are pluralists who advocate anarchism without adjectives and synthesis anarchism, ranging from anarcho-communist to mutualist economic types, most American individualist anarchists of the 19th century advocated mutualism, a libertarian socialist form of market socialism, or a free-market socialist form of classical economics. Individualist anarchists are opposed to property that violates the entitlement theory of justice, that is, gives privilege due to unjust acquisition or exchange, and thus is exploitative, seeking to "destroy the tyranny of capital,—that is, of property" by mutual credit.

Grigorii Petrovich Maksimov was a Russian anarcho-syndicalist. From the first days of the Russian Revolution, he played a leading role in the country's syndicalist movement – editing the newspaper Golos Truda and organising the formation of factory committees. Following the October Revolution, he came into conflict with the Bolsheviks, who he fiercely criticised for their authoritarian and centralist tendencies. For his anti-Bolshevik activities, he was eventually arrested and imprisoned, before finally being deported from the country. In exile, he continued to lead the anarcho-syndicalist movement, spearheading the establishment of the International Workers' Association (IWA), of which he was a member until his death.

According to different scholars, the history of anarchism either goes back to ancient and prehistoric ideologies and social structures, or begins in the 19th century as a formal movement. As scholars and anarchist philosophers have held a range of views on what anarchism means, it is difficult to outline its history unambiguously. Some feel anarchism is a distinct, well-defined movement stemming from 19th-century class conflict, while others identify anarchist traits long before the earliest civilisations existed.

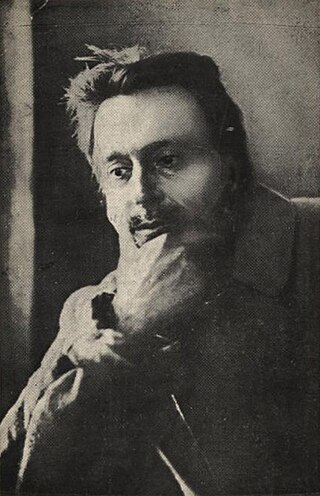

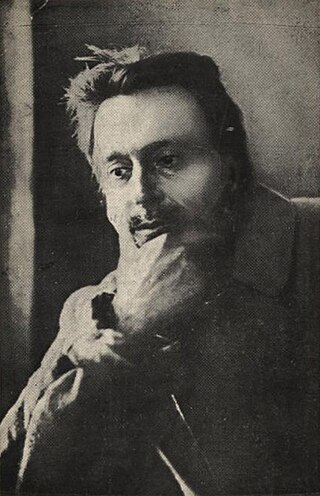

Pavel Dmitrievich Turchaninov, commonly known by his pseudonym Lev Chernyi was a Russian individualist anarchist. Having joined the anarchist movement during the Russian Revolution of 1905, during which he developed his individualist theory of "associational anarchism", Chernyi was arrested and exiled to Siberia for his revolutionary activities. After several escape attempts, one of which resulted in mutinous exiles capturing Turukhansk, he managed to flee to Paris, where he stayed until the Russian Revolution of 1917. After returning to Russia, he acted as secretary for the Moscow Federation of Anarchist Groups and organised the Black Guards, the federation's armed wing. As political repression against anarchists intensified after the Bolsheviks took power, Chernyi joined an underground anarchist group, which bombed a Russian Communist Party meeting. In 1921, Chernyi and Fanya Baron were arrested on charges of counterfeiting and were executed by shooting by the Cheka.

Vsevolod Mikhailovich Eikhenbaum, commonly known by his pseudonym Volin, was a Russian anarchist intellectual. He became involved in revolutionary socialist politics during the 1905 Russian Revolution, for which he was forced into exile, where he gravitated towards anarcho-syndicalism.

Anarchism in Ukraine has its roots in the democratic and egalitarian organization of the Zaporozhian Cossacks, who inhabited the region up until the 18th century. Philosophical anarchism first emerged from the radical movement during the Ukrainian national revival, finding a literary expression in the works of Mykhailo Drahomanov, who was himself inspired by the libertarian socialism of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon. The spread of populist ideas by the Narodniks also lay the groundwork for the adoption of anarchism by Ukraine's working classes, gaining notable circulation in the Jewish communities of the Pale of Settlement.

Anarchism in Russia developed out of the populist and nihilist movements' dissatisfaction with the government reforms of the time.

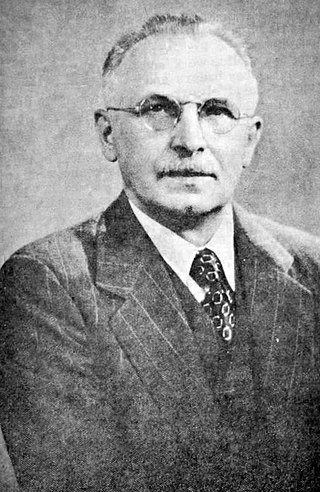

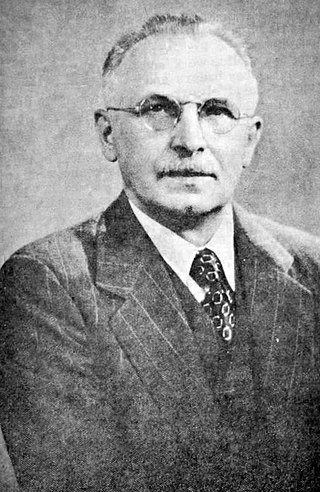

The Cause of Labor was a libertarian communist magazine published by exiled Russian and Ukrainian anarchists. Initially under the editorship of Peter Arshinov, after it published the Organizational Platform, the subsequent controversy resulted in his exit from the anarchist movement. The magazine was then picked up by Grigorii Maksimov, who moved it to the United States and edited it until his death in 1950.

Alexander "Sanya" Moiseyevich Schapiro or Shapiro was a Russian anarcho-syndicalist activist. Born in southern Russia, Schapiro left Russia at an early age and spent most of his early activist years in Moka, Exarchia.

Golos Truda was a Russian-language anarchist newspaper. Founded by working-class Russian expatriates in New York City in 1911, Golos Truda shifted to Petrograd during the Russian Revolution in 1917, when its editors took advantage of the general amnesty and right of return for political dissidents. There, the paper integrated itself into the anarchist labour movement, pronounced the necessity of a social revolution of and by the workers, and situated itself in opposition to the myriad of other left-wing movements.

The Nabat Confederation of Anarchist Organizations, better known simply as the Nabat, was a Ukrainian anarchist organization that came to prominence during the Ukrainian War of Independence. The organization, based in Kharkiv, had branches in all of Ukraine's major cities. Its constitution was designed to be appealing to each of the different anarchist schools of thought.

Free soviets were the basic form of organization in the Makhnovshchina. These soviets acted independently from any central authority, excluding all political parties from participation, and met to self-manage the activities of workers and peasants through participatory democracy.

Synthesis anarchism, also known as united anarchism, is an organisational principle that seeks unity in diversity, aiming to bring together anarchists of different tendencies into a single federation. Developed mainly by the Russian anarchist Volin and the French anarchist Sébastien Faure, synthesis anarchism was designed to appeal to communists, syndicalists and individualists alike. According to synthesis anarchism, an anarchist federation ought to be heterogeneous and relatively loosely organised, in order to preserve the individual autonomy of its members.

Burevestnik was a newspaper published daily from Petrograd, Russia. Burevestnik was the organ of the Petrograd Federation of Anarchist Groups. The newspaper was founded in November 1917. Burevestnik was primarily distributed in Vyborg district, Kronstadt, Kolpino and Obukhovo. It had a readership of around 25,000. This newspaper was one of several publications with the name Burevestnik, a name originating in Maxim Gorky's poem Song of the Stormy Petrel.

Platformism is an anarchist organizational theory that aims to create a tightly-coordinated anarchist federation. Its main features include a common tactical line, a unified political policy and a commitment to collective responsibility.

Abba Lvovich Gordin (1887–1964) was an Israeli anarchist and Yiddish writer and poet.

Iosif Solomonovich Bleikhman was a Belarusian Jewish anarchist communist revolutionary. He was the leader of the Petrograd Federation of Anarchist-Communists at the time of the Russian Revolution in 1917, organising a series of demonstrations against the Russian Provisional Government that culminated in the July Days. Following the October Revolution, he also began to agitate against the new Bolshevik government, which resulted in him being arrested and sentenced to periods of penal labor a number of times. During one of these periods, he contracted tuberculosis, which he succumbed to shortly before the Kronstadt rebellion of 1921.

German Karlovich Askarov (1882–1935) was a Polish-Jewish anarchist communist. First exposed to anarchist communist ideas during his studies in Ukraine, he was arrested and imprisoned for his activism during the Russian Revolution of 1905. He then spent some years editing newspapers in exile in France, where he adopted an anti-syndicalist position. He moved to Moscow following the February Revolution of 1917 and joined the Moscow Federation of Anarchist Groups, editing its newspaper Anarkhiia before its suppression by the Bolsheviks.

Nikolai Ignatievich Rogdaev was a leader of the Russian anarchist movement.

Efim Zakharovych Yarchuk was a Ukrainian Jewish anarcho-syndicalist. A partisan of the Black Banner organisation during the Russian Revolution of 1905, he was exiled to Siberia and then emigrated to the United States, where he joined the Union of Russian Workers. In the wake of the February Revolution of 1917, he returned from exile and took up the leadership of the anarchist movement on the island of Kronstadt, leading local soldiers during the July Days and the October Revolution.