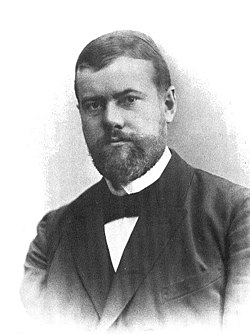

Value-freedom is a methodological position that the sociologist Max Weber offered that aimed for the researcher to become aware of their own values during their scientific work, to reduce as much as possible the biases that their own value-judgements could cause. [1]

Contents

The demand developed by Max Weber is part of the criteria of scientific neutrality. [2]

The aim of the researcher in the social sciences is to make research about subjects structured by values, while offering an analysis that will not be, itself, based on a value-judgement. According to this concept, the researcher should make of these values an “object”, without passing on them a prescriptive judgement. [3]

In this way, Weber developed a distinction between "value-judgement" and "link to the values". The "link to the values" describes the action of analysis of the researcher who, by respecting the principle of the value-freedom, makes of cultural values several facts to analyse without venturing a prescriptive judgement on them, i. e. without passing a value judgement. [4]

The original term comes from the German werturteilsfreie Wissenschaft , and was introduced by Max Weber. [5]