Partial list of attacks and incidents

The following is a partial list of VC and PAVN terror attacks and incidents. [2]

1960

- February 2: VC sacked and burned the Buddhist temple at Phuoc Thanh, Tây Ninh Province. They stabbed to death 17-year old Phan Van Ngoc, who tried to stop them.

- April 22: Some 30 VC raid Thoi Long, An Xuyên Province and attempt to abduct a farmer. A 16-year-old boy was shot dead.

- August 2: The VC executed two men at a school in Rau Ran, Phong Dinh Province.

- September 24: the VC sacked a school in An Lac, An Giang Province.

- September 28: the VC stopped a car carrying Father Hoang Ngoc Minh, a priest of Kontum parish, killing him and seriously wounding his nephew who was driving

- September 30: Truong Van Dang, 67, from Long Tri, Long An Province was taken to a "people's tribunal." He was condemned to death for purchasing two hectares of rice land and ignoring VC orders to turn the land over to another farmer. After the "trial" he was shot dead in his rice field.

- December 6: the VC dynamited the kitchen at the Saigon Golf Club, killing a Vietnamese kitchen helper and injuring two Vietnamese cooks.

1961

- March 22: A truck carrying 20 girls was dynamited on the Saigon-Vũng Tàu road. After the explosion, VC opened fire on survivors, killing two and wounding 10.

- May 15: Twelve Catholic nuns from La Providence order were traveling on Highway One toward Saigon. Their bus was stopped by VC near Tram Van, Tây Ninh Province. One of the nuns was killed after protesting

- July 26: Two Vietnamese National Assemblymen, Rmah Pok and Yet Nic Bounrit, both Montagnards, were shot and killed by VC near Da Lat. A schoolteacher, travelling with them on their visit to a Montagnard resettlement village, was also killed.

- September 20: One thousand main force VC soldiers stormed Phước Vĩnh, capital of Phước Thành Province, sacked and burned government buildings and beheaded the administrative staff. They held the capital for 24 hours before withdrawing.

- December 13: Father Bonnet, a French parish priest from Konkala, Kontum, was killed by a VC while visiting parishioners at Ngok Rongei.

- December 20: S. Fukai, a Japanese engineer at the Đa Nhim Hydroelectric Power Station, a Japanese government war reparations project to supply electric power to Vietnam, was kidnapped after being stopped at a roadblock and never seen again.

1962

- January 1: A South Vietnamese labor leader, Le Van Thieu, 63, was hacked to death by VC wielding machetes near Biên Hòa, in the rubber plantation on which he worked.

- January 2: Two South Vietnamese technicians working in the government's anti-malaria program, Pham Van Hai and Nguyen Van Thach, were killed by VC with machetes, 12 miles (19 km) south of Saigon.

- February 20: VC threw four hand grenades into a crowded village theater near Can Tho, killing 24 women and children. In all, 108 persons were killed or injured.

- April 8: the VC executed two wounded American prisoners of war near the village of An Châu. Each, hands tied, was shot in the face because he could not keep up with the retreating captors.

- May 19: A VC grenade attack on the Aterbea restaurant in Saigon wounded a German circus manager and the cultural attache from the German Embassy.

- May 20: A bomb exploded in front of the Hung Dao Hotel, Saigon, a billet for American servicemen, injuring eight Vietnamese and three Americans who were in the street at the time.

- May 30: the VC kidnapped missionaries Dan Gerber, Archie E. Mitchell, Dr. Eleanor Ardel Vietti from the Buôn Ma Thuột Leper colony, they were never seen again

- June 12: the VC ambushed a civilian passenger bus near Le Tri, An Giang Province, killing five men and women.

- October 20: a VC threw a grenade into a holiday crowd in downtown Saigon, killing six persons, including two children, and injuring 38 people.

- November 4: a VC threw a grenade into an alley in Can Tho, killing one American serviceman and two Vietnamese children. A third Vietnamese child was seriously injured.

1963

- January 25: the VC dynamited a passenger freight train near Qui Nhơn, killing eight passengers and injuring 15 others.

- March 4: Two Protestant missionaries Elwood Forreston, an American and Gaspart Makil, a Filipino, were shot dead at a VC road block between Saigon and Da Lat. Makil's twin babies were shot and wounded.

- March 16: the VC threw a grenade into a Saigon home where an American family was having dinner, killing a French businessman and wounding four other persons.

- April 3: the VC threw two grenades into a variety show performance at a private school near Long Xuyen, An Giang Province, killing a teacher and two other adults.

- April 4: the VC threw grenades into an audience attending an outdoor motion picture showing in Cao Lanh village in the Mekong Delta, killing four persons and wounding 11.

- May 23: the VC mined the main northern rail line, killing five civilian passengers. Twelve other passengers and crew were injured.

- May 31: Two explosions set off by VC on bicycles killed two Vietnamese and wounded ten others in Saigon.

- September 12: Vo Thi Lo, 26, a schoolteacher in An Phuoc, Kien Hoa Province, was found near the village with her throat cut. She had been kidnapped three days earlier.

- October 16: the VC exploded mines under two civilian buses in Kien Hoa and Quảng Tín Provinces, killing 18 civilians and wounding 23.

- November 9: Three grenades were thrown in Saigon, injuring a total of 16 persons, including four children.

1964

- February 9: Two Americans were killed and 41 wounded, including four women and five children, when a VC bomb was set off in a sports stadium during a softball game. A second bomb failed to explode.

- February 16: Three Americans were killed and 32 injured, most of them U.S. dependents, when the VC bombed the Kinh Do movie theater in Saigon.

- July 14: Pham Thao, chairman of the Catholic Action Committee in Quảng Ngãi, was executed when he returned to his native village of Pho Loi, Quảng Ngãi Province.

1965

- February 6: Radio Liberation announced that the VC had shot two American prisoners of war as reprisals against the Vietnamese government, which had sentenced two VC to death.

- March 30: A VC car bomb exploded outside the American Embassy in Saigon, killing two Americans, 19 Vietnamese and one Filipino and injuring 183 others.

- June 25: The VC bombed the My Canh floating restaurant in Saigon, killing 27 Vietnamese, 12 Americans, two Filipinos, one Frenchman, one German and injuring more than 80 persons.

- August 18: A bomb at the Police Directorate office in Saigon killed six and wounded 15.

- October 4: One of two planted bombs exploded at the Cong Boa National Sports Stadium, killing eleven Vietnamese, including four children and wounding 42 persons.

- October 5: A bomb went off, apparently prematurely, in a taxi on a main street in downtown Saigon, killing two Vietnamese and wounding ten others.

- December 4: a VC bomb exploded in front of the Metropole Bachelor Enlisted Quarters killing seven Vietnamese civilians, one U.S. Marine and one New Zealand soldier. 137 were injured, including 72 Americans, three New Zealanders and 62 Vietnamese.

- December 12: Two VC platoons killed 23 South Vietnamese canal construction workers asleep in a Buddhist Pagoda in Tan Huong, Dinh Tuong Province, seven others were wounded.

- December 30: Saigon editor Tu Chung of the newspaper Chinh Luan was shot dead as he arrived home for lunch. Earlier he had published the texts of threatening notes he had received from the VC.

1966

- January 7: A Claymore mine exploded at Tan Son Nhut International Airport gate, killing two persons and injuring 12.

- January 17: VC in Kien Tuong Province detonated a mine under a highway bus, killing 26 civilians, seven of them children. Eight persons were injured and three missing.

- January 29: the VC killed a Catholic priest, Father Phan Khac Dau, 74, at Thanh Tri, Kien Tuong province. Five other civilians, including a church officer, were also killed.

- February 2: A VC squad ambushed a jeep of South Vietnamese information workers, killing six and wounding one in Hậu Nghĩa Province.

- February 14: Two mines exploded beneath a bus and a three-wheeled taxi on a road near Tuy Hòa, killing 48 farm laborers and injuring seven others.

- March 18: Fifteen Vietnamese civilians were killed and four injured by the explosion of a mine on a country road 8 km west of Tuy Hòa.

- May 22: the VC killed 18 sleeping men, a woman and four children during an attack on a housing center for canal workers in An Giang Province.

- September 10: On the eve of South Vietnam's Constituent Assembly elections, the VC staged 166 separate incidents of intimidation, abduction and assassination. Polling places were destroyed.

- September 11: On election day, the VC killed 19 voters and wounded 120, in fire on polling places, mining of roads and in individual assassinations.

- September 24: American troops freed 11 persons from a VC prison in Phu Yen province who reported that 70 fellow prisoners were deliberately starved to death and 20 others tortured until they died.

- October 11: Allied forces discovered a VC prison complex in Bình Định Province containing the bodies of 12 South Vietnamese who had been machine gunned and grenaded by fleeing guards.

- October 22: A youth worker in Binh Chanh, Gia Định Province, was shot and killed by VC while asleep in his home.

- October 24: The Huế-Quảng Trị bus ran over a mine in Phong Điền District, Thừa Thiên Province, 15 passengers were injured.

- October 27: A grenade was thrown into a home in Ban Me Thuot, Darlac Province, killing a 63-year-old man and a nine-month old child; seven other persons were wounded.

- November 1: the VC directed long-range recoilless rifle fire into downtown Saigon during National Day celebrations killing seven South Vietnamese and one American officer.

- November 2: A grenade was thrown by a VC at Phú Thọ Racetrack, Saigon, killing two persons and wounding eight others, including two children.

- November 3: VC squads infiltrated the outskirts of Saigon and fired 24 recoilless rifle shells on the city. Among the buildings hit were Bến Thành Market, Grall Hospital, Saigon Cathedral, a seminary chapel and several private homes. Eight persons were killed and 37 seriously wounded.

- November 4: the VC mortared a village in Hau Nghia province, killing one civilian and wounding eight. The VC attacked an outpost in Tay Ninh Province, killing six civilians and wounding two Civil Operations and Revolutionary Development Support (CORDS) team members.

- November 7: A VC squad on Provincial Road 8, Quang Duc Province, abducted a hamlet chief and deputy chief.

- November 8: In Châu Đốc Province, a 53-year-old woman was tortured and shot to death; a note pinned to her body accused her of supporting the South Vietnamese government.

- November 16: A VC bicycle bomb exploded on Nguyen Van Thoai Street, Saigon wounding two South Vietnamese soldiers and a civilian.

- November 19: Eight VC mortar rounds on Can Giuoc, Long An Province, killed two children; 12 civilians were wounded. 20 mortar rounds hit Can Duoc, wounding five civilians.

- November 23: Three VC dressed in ARVN uniforms killed a policeman guarding a bridge at Khanh Hung (Soc Trang), Ba Xuyen Province. While escaping, they threw two grenades, wounding seven civilians and two soldiers.

- November 30: the VC shelled Tân Uyên market, Bien Hoa Province, killing three civilians and wounding seven.

- December 4: A village chief in Gia Định Province was abducted from his home in Phu Lam by four VC and executed.

- December 7: Tran Van Van, Constituent Assemblyman, was assassinated by a VC while en route to the National Assembly.

- December 10: A VC threw a grenade into the Chieu Hoi district playground, Binh Duong City, severely injuring three children.

- December 10: A taxi on Highway 29, Phong Dinh Province ran over a mine. Five passengers, all women, were killed and the driver badly wounded.

- December 13: a bomb explosion killed three CORDS personnel and wounded nine who were attending a course at the Ca Mau school, An Xuyen Province.

- December 20: A VC squad infiltrated a hamlet in Quảng Tín Province, kidnapped a former VC who recently defected and executed him.

- December 27: National Constituent Assemblyman, Dr. Phan Quang Dan, narrowly escaped death when a car bomb detonated as Dr. Dan opened the door. Dan escaped with minor wounds but a woman passerby was killed and five civilians wounded.

1967

- January 6: A South Vietnamese policeman in Tan Chu, Kien Phong Province, was shot and killed while members of his family looked on.

- January 7: An explosion destroyed a school and health station in Hồng Ngự District, Kien Phong Province.

- January 8: In An Xuyên Province, VC threw a grenade into the house of a hamlet chief. One of his children was killed and three other civilians were wounded.

- January 12: Three civilians were killed and three ARVN soldiers wounded in an ambush of a truck on Highway 14, 2 km south of Tân Cảnh village.

- January 15: At Thanh Tho, Quảng Tín Province, the VC shot a merchant when he refused to give them two oxen.

- January 21: VC forced their way into Buôn Hồ, Darlac Province, gathered the people for a propaganda lecture and kidnapped six young men.

- February 6: the VC raided Lieu Tri, Quảng Tín Province and abducted a teacher and a local official. The teacher was killed. A grenade was thrown onto the porch where the Kontum deputy province chief was entertaining a group of South Vietnamese officials. The provincial Chief of Education was killed instantly; the Chief of Montagnard Affairs and another official died of wounds the next day. Eight others were seriously wounded.

- March 4: Two badly wounded prisoners survived after VC prison guards near Cần Thơ tied 12 South Vietnamese captives together, shot and stabbed them before fleeing from advancing ARVN troops; both survivors lived despite having their throats cut.

- March 5: In a night raid, the VC killed two young CORDS workers in Vinh Phu, Phú Yên Province. Seven additional CORDS team members were killed in the ensuing gunfight and four were wounded.

- March 30: Recoilless rifle fire directed at the homes of families of ARVN troops demolished 200 houses and killed 32 men, women and children in the capital city of Bac Lieu Province.

- April 13: A South Vietnamese entertainment troupe was the target of nocturnal raid in Lu Song hamlet, near Da Nang. The team chief and his deputy were killed; two team members were wounded.

- April 14: the VC kidnapped Nguyen Van Son in Bình Chánh District, Gia Định Province; he was a candidate in the elections for village council.

- April 16: A squad enters Cam Ha, Quảng Nam Province and killed an election candidate. One child was killed and three civilians wounded.

- April 18: Sui Chon hamlet northeast of Saigon was attacked by VC who killed CORDS team members, wounded three and abducted seven; three of those killed are young girls, whose hands were tied behind their backs before they were shot in the head. One third of the hamlet's dwellings are destroyed by fire.

- April 26: Nguyen Cam, chief of Ba Dan hamlet, Quảng Nam Province, was shot and killed by a VC. Cam had been a candidate in recent elections.

- May 10: A bus loaded with South Vietnamese civilians ran over a land mine near Than Bach Thach, Phu Bon Province. One passenger was killed; the driver and five passengers were wounded.

- May 16: In two separate attacks in Quảng Tin and Quảng Trị Provinces, the VC killed eight CORDS team members and injured five.

- May 24: The information officer of Phu Thanh, Bien Hoa Province, and his two children were killed by grenades thrown into their home.

- May 29: VC frogmen emerged from the Perfume River in Huế to blow up a hotel housing members of the ICC. No member of the Indian-Canadian-Polish team was hurt, but five South Vietnamese civilians were killed and 15 wounded. The hotel was 80 percent destroyed.

- June 2: two VC platoons made a night raid on a Chieu Hoi camp in Long An Province injuring five ARVN and five civilians.

- June 27: Twenty-three civilians were killed when their bus struck a mine in Binh Duong Province, southeast of Lai Khê.

- July 6: Several children walking on the road in Cam Pho hamlet, Quảng Nam Province, were wounded when a passing truck exploded a VC anti-tank mine. One child died of wounds.

- July 13: An explosion in a Huế restaurant killed two Vietnamese. Twelve Vietnamese, seven Americans and one Filipino were injured.

- July 14: VC dressed in ARVN uniforms captured a prison in Quảng Nam Province, releasing about 1,000 of the 1,200 inmates; they executed 30 in the prison yard. Ten civilians were killed and 29 wounded as the VC fought their way out of the area.

- July 25: VC appeared at homes in Bình Triệu, Long An Province and kidnapped four men, a woman and the woman's 16-year-old son. All six were found the following morning along Highway 13, shot in the head with their hands tied behind their backs.

- August 5: During a special civics class in a secondary school in An Xuyen Province, part of the September election "get out the vote" campaign, a VC gave a small girl a hand grenade with the pin extracted and told her to carry it carefully to her teacher. At the classroom door the child dropped the grenade, killing herself and injuring nine children.

- August 24: the VC kill one and wound four when they detonated a charge at the home of a Vietnamese policeman in Cần Thơ.

- August 26: Twenty-two civilians died and six were injured when their bus struck a mine in Kien Hoa Province.

- August 27: A week before presidential and senate elections, the VC stepped up their activities. A recoilless rifle and mortar attack on Cần Thơ killed 46 and injured 227. Ten die and ten were injured in an attack on a CORDS team in Phước Long Province. Fourteen civilians, including five children, were wounded by mortar fire southeast of Ban Me Thuot. Two civilians died and one was wounded in an attack on a hamlet in Binh Long Province. Six civilians were kidnaped from Phuoc Hung village in Thừa Thiên Province.

- August 29: Groups of VC infiltrated four hamlets in Thanh Binh district, Quảng Nam Province, killing two civilians and abducting six, including an inter-family chief.

- September 1: VC explosives blasted six craters in National Route 4 in Dinh Tuong Province, stopping all vehicular traffic except an ARVN ambulance bus which ran over a pressure mine, killing 13 passengers, injuring 23.

- September 3: Shortly after polls open in Tuy Hòa the VC detonated a bomb hidden in a polling place. Three voters were killed and 42 wounded. Election morning attacks, including long-range shellings, claimed 48 lives.

- November 8: The Ky Chanh refugee center in Quảng Tín Province was infiltrated by VC who killed four persons, wounded nine others and kidnapped nine more; they also set fire to the camp's school.

- December 5: in the Đắk Sơn massacre two VC battalions attacked Đắk Sơn village and killed 114 to 252 Montagnard villagers.

- December 14: Bui Quang San, a member of South Vietnam's lower house, was gunned down in his home near Saigon. Two days before his death, San told friends of receiving a letter from the VC threatening his life. His mother, first wife and six children were killed in an earlier VC raid in Hội An. Saigon reported a total of 232 civilians killed by acts of terrorism in one week.

- December 16: During the intermission at a classical drama at the University of Saigon, a VC appeared on stage and began a propaganda speech. A student attempted to climb to the stage and was shot in the stomach. Two other students were shot in the melee that follows.

1968

- January 20: A VC armed propaganda team entered Tam Quan, Bình Định Province, gathered 100 people for a propaganda session; one prominent village elder objected and was shot to death.

- January 31 - February 28: in the Massacre at Huế the VC killed between 2,800 and 6,000 captured soldiers, Government officials and civilians.

- April 6: A VC group entered That Vinh Dong, Tây Ninh Province; they sold several thousand piasters worth of "war bonds" and then departed, taking with them a school teacher, the hamlet chief's two daughters and nephew and six other males aged 15 or 16.

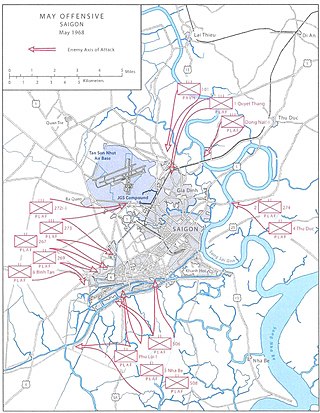

- May 5 - June 22: some 417 rockets were fired indiscriminately into Saigon, chiefly in the densely-populated Fourth District killing 115 and wounding 528.

- May 29: A VC unit stopped all traffic on Route 155 in Vĩnh Bình Province; 50 civilians were kidnapped, including a Protestant minister; two buses and 28 three-wheeled taxis were burned.

- June 28: in the Son Tra massacre 73 civilians and 15 CORDS workers were killed in the attack and a further 103 civilians were wounded. 570 homes were destroyed in the attack and the resulting fires leaving almost 2,800 people homeless

- July 28: Four VC, detonated a 60-pound plastique charge in city room of Chợ Lớn Daily News, the most prominent of city's seven Chinese language newspapers, after ordering workers out of building; the four escaped before police arrived.

- September 12: A VC report (captured in Bình Dương Province) from the Châu Thành District Security Section to the provincial Party Central Committee stated that seven prisoners in the district's custody were shot prior to an expected allied sweep operation, the report read: "we killed them to make possible our safe escape.”

- September 26: A grenade was thrown into Bến Thành market, killing one person and wounding 11.

- December 11: A VC unit appeared at the home of the provincial People's Self-Defense Force chief in Tri Ton, Châu Đốc Province; they tied him up and then executed him.

1969

- January 6: The Vietnamese Minister of Education, Dr. Le Minh Tri, was killed when two VC on a motorcycle threw a hand grenade through the window of the car in which he was riding.

- February 7: A Satchel charge exploded in the Cần Thơ market place, killing one and wounding three.

- February 16: the VC invaded and occupied Phuoc My village, Quảng Tín Province, for several days. Later, survivors describe a series of acts: a 78-year old villager was shot for refusing to cut down a tree for a fortification; a 73-year-old man was killed when he could not or would not leave his home, pleading that infirmities prevented him from walking; an 11-year-old boy was stabbed and several families grenaded in their homes.

- February 19: A bicycle bomb exploded in a shop in Truc Giang, Kien Hoa Province, killing six civilians and wounding 16.

- February 24: VC entered a Catholic church in Quảng Ngãi Province and assassinated the priest and an altar boy.

- February 26: A bicycle bomb exploded near a pool hall in Kien Hoa province, killing a child and wounding three other persons.

- March 4: the Rector of Saigon University, Professor Tran Anh, was shot by VC on a motorcycle; previously he had been notified that he was on the "death list" of the "Suicide Regiment of the Saigon Youth Guard."

- March 6: An explosive charge exploded next to a wall at Quảng Ngãi city hospital, killing a maternity patient and destroying two ambulances.

- March 9: VC entered Xom Lang, Gò Công Province and took Mrs. Phan Thi Tri from her home to a nearby rice field where they beheaded her, explaining that her husband had defected from the VC. A VC unit attacked Loc An, Lac My and Loc Hung villages in Quảng Nam province, killing two adults and kidnapping ten teenage boys.

- March 13: Kon Sitiu and Kon Bobanh, two Montagnard villages in Kon Tum Province, were raided by VC; 15 persons killed; 23 kidnapped, two of whom were later executed; three long-houses, a church and a school burned. A hamlet chief is beaten to death. Survivors said that the VC explained that: "We are teaching you not to cooperate with the government.”

- March 21: A Kon Tum Province refugee center was attacked for the second time by a PAVN battalion using mortars and B-40 rockets. Seventeen civilians were killed and 36 wounded, many of them women and children. A third of the center was destroyed.

- April 4: A pagoda in Quảng Nam Province was dynamited by the VC, killing four persons, wounding 14.

- April 9: VC attacked the Phu Binh refugee center, Quảng Ngãi Province and set fire to 70 houses, leaving 200 homeless. Four persons were kidnaped.

- April 11: A satchel charge exploded in the Dinh Thanh temple, Long Thanh village, Phong Dinh Province, wounding four children.

- April 15: A VC armed propaganda team invaded An Ky refugee center, Quảng Ngãi Province, and attempts to force out the people living there; nine were killed and ten others wounded.

- April 16: The Hoa Dai refugee center in Bình Định Province was invaded by a VC armed propaganda team. The refugees were urged to return to their former (VC dominated) village, but refused; the VC burned 146 houses.

- April 19: Hieu Duc district refugee center, Quảng Nam Province, was invaded and ten persons kidnapped.

- April 23: Son Tinh district refugee center, Quảng Ngãi Province, was invaded; two women were shot and 10 persons kidnapped.

- April 27: the VC kidnapped five West German members of the Maltese Relief Service near Da Nang. Only two survived the four years of captivity.

- May 6: Le Van Gio, 37, was kidnapped and later shot for refusing to pay taxes to a VC agent who entered his village of Vinh Phu, An Giang Province.

- May 8: VC sappers detonated a charge outside the Saigon Central Post Office, killing four civilians and wounding 19.

- May 10: Sappers exploded a charge of plastique in Duong Hong, Quảng Nam Province, killing eight civilians and wounding four.

- May 12: A VC sapper squad attacked Phu My, Bình Định Province, with satchel charges, rockets and grenades; 10 civilians were killed, 19 wounded; 87 homes were destroyed.

- May 14: Five PAVN 122mm rockets hit the residential area of Da Nang, killing five civilians and wounding 18.

- June 19: In Phu My, Thừa Thiên Province, the VC assassinated a 54-year-old man and his 70-year-old mother.

- June 24: A PAVN 122mm rocket struck the Thanh Tam Hospital in Ho Nai, Biên Hòa Province, killing one patient.

- June 30: PAVN/VC mortar shells destroyed the Phuoc Long pagoda in Chanh Hiep, Bình Dương Province; one Buddhist monk was killed and ten persons wounded. Three members of the People's Self-Defense Force were kidnapped from Phu My, Biên Hòa Province.

- July 2: Two VC assassins entered a hamlet office in Thai Phu, Tây Ninh province, shoot and wound the hamlet chief and his deputy.

- July 17: A grenade was thrown into Cho Con market, Da Nang, wounding 13 civilians, mostly women.

- July 18: Police reported two incidents of B-40 rockets being fired into trucks on the highway, one in Quang Duc Province in which three civilians were wounded and one in Darlac Province which killed the driver.

- July 19: A VC unit attacked the Chieu Hoi center in Vĩnh Bình Province killing five persons, including two women and a youth, and wounding 11 civilians. The VC seized and shot Luong Van Thanh, a People's Self-Defense Force member in Tan Hoi Dong, Định Tường Province.

- July 30: the PAVN/VC rocketed the refugee center of Hung My, Bình Dương, wounding 76 persons.

- August 5: Two grenades were thrown into the elementary school in Vinh Chau, Quảng Nam Province, where a school board meeting was taking place. Five persons are killed and 21 are wounded.

- August 7: A series of explosions was detonated outside an adult education school for Vietnamese military in Chợ Lớn, killing eight and wounding 60.

- August 13: Officials in Saigon reported a total of 17 PAVN/VC terror attacks on refugee centers in Quảng Nam and Thừa Thiên Provinces, leaving 23 persons dead, 75 injured and a large number of homes destroyed or damaged.

- August 21: the VC infiltrated Ho Phong, Bạc Liêu Province, and killed three People's Self-Defense Force members and wound two others.

- August 26: in a VC attack outside Hoa Phat, Quảng Nam Province; a nine-month-old baby, three children between ages six and ten, two men and a woman, a total of seven, were all shot at least once in the back of the head.

- September 6: PAVN/VC rocket and mortar hit the training center of the National Police Field Force in Dalat, killing five trainees and wounding 26.

- September 9: South Vietnamese officials reported that nearly 5,000 South Vietnamese civilians have been killed by PAVN/VC terror during 1969.

- September 20: the PAVN/VC attacked Tu Van refugee center in Quảng Ngãi Province, killing 8 persons and wounding two, all families of local People's Self-Defense Force members. In nearby Bình Sơn District, eight members of a police official's family were killed.

- September 24: A bus hit a mine on Highway 1, north of Đức Thọ, Quảng Ngãi Province; 12 passengers are killed.

- October 13: A grenade was thrown in the Vi Thanh District Chieu Hoi center, killing three civilians and wounding 46; about half those wounded are dependents. The VC kidnapped a Catholic priest and a lay assistant, from the church at Phu Hoi, Biên Hòa Province.

- October 27: the PAVN/VC booby-trapped the body of a People's Self-Defense Force member whom they have killed. When relatives came to retrieve the body the subsequent explosion killed four of them.

1970-1975

- 11 June 1970: in the Thanh My massacre the VC killed 74 civilians and wounded over 160 and destroyed 156 houses in Thanh My hamlet, Phu Thanh village, Quảng Nam Province

- 29 March 1971: in the Duc Duc massacre the PAVN/VC killed 103 civilians and abducted 37 and destroyed 1,500 homes in Duc Duc District, Quảng Nam Province.

- 9 January 1972: a VC threw a grenade into a youth rally in Quy Nhon in an attempt to kill the Bình Định province chief, the grenade killed two teachers and seven students and wounded 110 others. [13]

- 29 April – 2 May 1972: in the Shelling of Highway 1 indiscriminate PAVN artillery fire killed approximately 2000 civilian refugees fleeing down Highway 1 from Quảng Trị.

- April–July 1972: Allied intelligence sources said that the PAVN/VC had executed 250-500 South Vietnamese government officials and imprisoned more than 6,000 during their occupation of Bình Định province. [14]

- 9 September 1972: VC sappers attacked a refugee camp near Danang, killing 20 refugees and wounding 94. [15]

- 30 August 1973: in the Shelling of Cai Lay schoolyard 20 civilians were injured by indiscriminate VC fire on a school in Cai Lậy District.

- 15–19 March 1975: an unknown number of civilians were killed by indiscriminate PAVN fire on the “Convoy of tears” retreat down Route 7 following the Battle of Ban Me Thuot