Early history

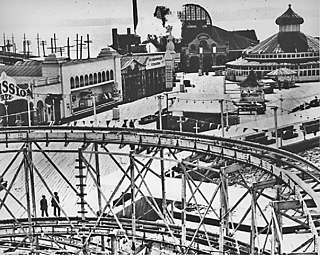

White City was originally envisioned to be like Dreamland, a park in Coney Island, Brooklyn that was widely praised for its amazing spectacles. [10] The park's ambitious plan faced obstacles. The newspapers reported on the construction rush, which led to an incident in February 1905 when three plasterers fell 25 feet (7.6 m) from a scaffold, as they worked on a ceiling. [11] After the park had opened, there was one occasion when a ride malfunctioned; a patron was killed, and two other patrons were injured. [12] A year later, the park's roller coaster also malfunctioned, injuring twelve people. [13] The new park's operation appeared as safe as similar parks, and almost from the beginning, White City was very well received. The city experienced dramatic increases in ridership on the public transportation that took people to White City. In August 1905, ridership on the South Side 'L' Train rose by 11,000 fares over the number of riders from a year earlier, an increase directly attributed to the opening of the park. [14]

1950s and 1960s newspaper articles associated the park with an owner named Aaron Jones who was a Chicago entrepreneur who had been a successful operator of a penny-arcade business. Jones had visited the World's Columbian Exposition of 1893 and been so impressed that he aspired to create an amusement park that was similar to it. [15] Earlier 1905–1915 newspaper accounts had said the owners were two Chicago brothers, Morris and Joseph Beifeld. Morris was frequently called the president of the corporation that operated the park, and the 1910 United States Census states that he is President of the White City Amusement Park. Newspaper articles that reported declining business in 1911 called Morris the "President of White City Construction Company, which operates the Chicago amusement park." [16] Joseph was the proprietor of the Hotel Sherman (originally called the Sherman House) but in an article about self-made millionaires, the Chicago Tribune noted that he was not only a hotel magnate but "principal stockholder in the White City Amusement and Construction Company." [17] Also in 1907, the Tribune referred to the White City Amusement Park's executives as "President Joseph Beifeld, Treasurer Aaron J. Jones, and General Manager Paul D. Howse." [18] Mr. Howse had been a journalist in Chicago, and his July 10, 1933 obituary stated that he was one of White City's founders and its first general manager.

Admission was ten cents in the early years, and newspaper ads noted that White City was open rain or shine. In good weather, patrons could enjoy "...the spacious plaza, the outdoor sports and amusements", and if the weather was inclement, there was "...the excellent vaudeville show, the Chicago fire, ...the Baby Incubators, [and] the Wild Animals show..." [19] In August 1906, the list of features at the park included these: Big Otto's Trained Wild Animal Show, Hale's Tours of the World, Flying Airships, Temple of Palmistry, Scenic Railway, Trip to Mars, Infant Incubators, Electric Cooking, the Midget City, and the Chutes. [20]

The park information mentioned a small Ferris wheel that had six cars and a miniature railroad. [21] The park also featured the first Shoot-the-Chutes ride in Chicago. [22] [23] It also featured a roller coaster and the Garden Follies Dancers. [23] The park featured regular outdoor concerts, [24] and it had a roller rink. [25] Hal Pearl then known as 'Chicago's Youngest Organist' was the organist at the roller rink and sometimes gave concerts. The park hosted burlesque shows, [26] and performers like Annette Kellerman, Bill Cody and Sophie Tucker performed at the park regularly. [4] [27] Daredevil aeronautic shows of performers like Horace Wild were also common at the park. [28]

Midget City was a popular exhibit that featured 50 men and women who all had dwarfism; at the time, the word used to describe them was 'midgets,' and working the carnival circuit was one of the few jobs open to them. The exhibit showed a miniature city, with a miniature mayor, and even miniature horses. Also popular was the "Chicago Fire" exhibit, which featured an exhibit described as a faithful reproduction of the burning of the city: "... a panoramic display... in miniature, with all the addenda of realistic fire and smoke effects and crumbling of buildings..." [29]

Beginning in the summer of 1906, the Chicago Tribune newspaper made use of White City to hold an annual benefit for Chicago's hospitals, with the proceeds devoted to helping babies who needed care. In addition to the regular exhibits, there were well-known bands of the day that came to perform: for example, in August 1907, the Kilties, a Canadian band that played Scottish music, performed traditional Scottish folk music and folk dances. [18] The Baby Incubators exhibit, a feature of several other fairs and parks of that time, attracted much attention and many donations. There is evidence that tiny infants were displayed at White City from the park's earliest days. The stories of the struggle for survival of these so-called "incubator babies" even made the west coast newspapers. (For example, a story of a 1-pound, 4 oz. infant from Indiana, called the "Tiniest Baby in the World", was written up in the San Francisco Chronicle , July 20, 1905, p. 2) At the time, not every hospital had incubators, and the Chicago Tribune was among the newspapers that used the Baby Incubator displays to raise money so that all hospitals in the Chicago area would have them. [30] By 1908, another area amusement park, Riverview Park, was also involved in this cause. [31] From 1906 through 1920, a doctor, identified in some sources as simply "Dr. Couney", and elsewhere as Dr. M.A. McConey or Dr. M.A. Couney [32] maintained an exhibit of an incubator in which live infants were tended, including the daughter of the editor of the Chicago Tribune. [1]

In October 1910, White City served as the home of a major Christian evangelistic crusade. Dr. J. Wilbur Chapman and Mr. Charles M. Alexander made use of the ballroom, which seated nearly 4000, and they brought with them a chorus of several hundred people. The evangelists planned to make appearances all over the Chicago area during the month, but wanted to do something very memorable to begin their revival. They felt that White City was the place to launch the crusade in a very spectacular fashion. [33]

In late September 1911, White City experienced a serious fire, as flames swept through the southern section of the park. Newspaper reports said it started in a storage area near the railway, and it attracted a large crowd. A strong north wind kept the fire contained to the rear of the park, which prevented a nearby 200 foot tower in the center of the boardwalk from being destroyed. Firefighters were able to put the fire out without anyone sustaining serious injuries. The scenic railway and half of the Figure 8 took the brunt of the damage. [34]

During the early 1920s, the park continued to be involved with charity benefits. A Chicago Tribune advice columnist whose pen name was "Sally Joy Brown" sponsored a children's event beginning in 1923. Sally Joy's column had become famous for getting readers to do good deeds to help the poor, and even children often participated in lending a hand. Now, the newspaper wanted to provide free access to the park for 100 lucky boys and girls who sent in the best letters explaining why they wanted to come to Sally's party and spend a day at White City. Many of the children who responded had never been to an amusement park. This content continued into the early 1930s, when the "Sally Joy" of that time was a woman named Anna Nangle. [35]

White City served as the place of assembly and departure point for the first Goodyear Blimp, called the "Wingfoot Air Express". [4] Both B. F. Goodrich and Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company assembled dirigibles at the park for the United States Navy. [4] A dirigible serviced the park, bringing passengers from Chicago's Grant Park. On July 21, 1919, the dirigible run crashed into the Illinois Trust & Savings Building on LaSalle Street, killing twelve and injuring twenty-eight. [36] The pilot, John A. Boettner was saved by his parachute. He was arrested, pending an investigation of the tragedy, but later released without charges. [37] This crash resulted in the closure of the Grant Park Airstrip and the creation of the Chicago Air Park (currently Midway International Airport).

There was another fire at the park in early July 1925, and although it did some damage, it was contained without any serious injuries. [38] A later fire in June 1927, however, was much more serious. Starting in the ballroom, it spread and did over $200,000 in damage; the tower that was not harmed in the 1911 fire finally was destroyed in this blaze. Some historians believe the 1927 fire signalled the beginning of the end for the park. [15]

Later history

White City had experienced periodic financial problems because attendance was dependent on the economy. As far back as 1915, there had been a question of whether the park's lease would be renewed, but finally the landlord, Chicago business mogul J. Ogden Armour re-negotiated it and the park remained open. [39] But the Depression, along with the ongoing problems from the fires of 1925 and 1927, had a very negative impact on White City. Although 1930 still wasn't too bad for White City, [40] with each successive year, attendance declined, and by 1933, the company that operated it was unable to pay the taxes that were due, causing the park to be placed in receivership. [4]

White City continued to deteriorate until it was condemned in 1939 and its facilities were auctioned off in 1946. [23]

In 1945, the land on which White City had stood was designated for a co-operative housing development for African-Americans. The irony, as reporters from black newspapers like the Chicago Defender quickly pointed out, was that the history of the White City Amusement Park had been one of de facto segregation. Black people were discouraged from attending during the park's early years. As far back as 1912, there had been comments that the name "White City" was very appropriate, given how it seemed to be a park for white people, and where black people served as objects of ridicule: one game was called the "African Dip", and it involved patrons throwing projectiles at the head of a black person, and trying to hit him. [41] Black columnists were irate that some black men willingly took these kinds of jobs. [42] Admission policies were desegregated when the neighborhood changed and more people of color resided nearby. The housing development was to be called Parkway Gardens, and at the time, it was seen as a hopeful sign that a neglected neighborhood would have new housing. [43]

The same anti-black policies that had beset the amusement park also applied to the roller rink at the park. The rink was still open, and during the 1940s, it became the site of demonstrations and brawls as Blacks fought for their right to roller skate indoors. [25] In 1942, the Congress of Racial Equality was involved in one of these rallies. [44] In 1946, the Congress of Racial Equality sued the management of the rink, saying it was violating the Illinois Civil Rights Law. [45] Eventually, the White City rink was desegregated and changed its name to Park City. The Park City rink closed in 1958. [44]

Today, White City Amusement Park, which was once considered the equal of other turn of the century parks like Coney Island, is all but forgotten; but in its heyday, it was known as "the city of a million electric lights", because its tower was an amazing sight that could be seen for 15 miles. [46]