As the Palais de Luxe

Great Windmill Street took its name from a windmill that stood there from the reign of King Charles II until the late 18th century. In 1909 a cinema, the Palais de Luxe, opened on the site. [1] It stood on the corner of a block of buildings that included the Apollo and Lyric theatres, where Archer Street joined Great Windmill Street, just off Shaftesbury Avenue. The building complex incorporates Piccadilly Buildings, an 1897 building which housed the offices of British Mutoscope and Biograph Company, an early producer of films.

The Palais de Luxe was one of the first places where early silent films were shown. As larger cinemas were opened in the West End, business slowed and the Palais de Luxe was forced to close. [1] It was re-opened briefly by Elsie Cohen in 1929 when it was briefly the first "art cinema" in Britain showing foreign films. Cohen would re-establish the idea at the Academy Cinema in Oxford Street in 1931. [2]

The Windmill

In 1930, after her husband's death, Laura Henderson bought the Palais de Luxe building and hired F. Edward Jones, an architect, to remodel the interior to a small 320-seat, two-tier (stalls and circle) theatre. [1] It was then renamed the Windmill. It opened on 15 June 1931, as a playhouse with a new play by Michael Barringer called Inquest . [1] Its existence as a theatre was short and unprofitable, and it soon returned to screening films, such as The Blue Angel (1930) starring Marlene Dietrich. [1]

Mrs Henderson hired a new theatre manager, Vivian Van Damm, who developed the idea of the Revudeville—a programme of continuous variety that ran from 2:30 pm until 11 pm. They began to put on shows with singers, dancers, showgirls, and specialty numbers. The first Revudeville act opened on 3 February 1932, [1] featuring 18 unknown acts. These continued to be unprofitable; in all, the theatre lost £20,000 in the first four years after its opening. [3]

Amrit Walia, the co-founder, said: "In the 1930s Laura Henderson famously broke conventions and challenged norms to create the famous institution known as the Windmill Theatre". [4]

Windmill Girls

A breakthrough came when Van Damm began to incorporate glamorous nude females on stage, inspired by the Folies Bergère and Moulin Rouge in Paris. This coup was made possible by convincing Lord Cromer, then Lord Chamberlain, in his position as the censor for all theatrical performances in London, that the display of nudity in theatres was not obscene: since the authorities could not credibly hold nude statues to be morally objectionable, the theatre presented its nudes — the legendary "Windmill Girls" — in motionless poses as living statues or tableaux vivants . The ruling: 'If you move, it's rude.' The Windmill's shows became a huge commercial success, and the Windmill girls took their show on tour to other London and provincial theatres and music halls. The Piccadilly and Pavilion theatres copied the format and ran non-stop shows, reducing the Windmill's attendance.

Tableaux vivants

Van Damm produced a series of nude tableaux vivants based on themes such as Annie Oakley, mermaids, American Indians, and Britannia. Typically, nude performers would assemble onstage with the curtain down (i.e. out of sight of the audience) and then strike poses before the curtain went up. The performers would then hold those poses, remaining perfectly still until the curtain came down again. Alternatively, a succession of nude performers would stand in the wings on trolleys and be wheeled onstage from the wings by a fully-clothed stage-hand. In all cases the performers themselves had to remain completely motionless, as if they were a statue made of stone or bronze.

Later, movement was introduced in the form of the fan dance, where a naked dancing girl's body was concealed by fans held by herself and four female attendants. At the end of the act the girl would stand stock still, and her attendants would remove the concealing fans to reveal her nudity. The girl would then hold the pose for about ten seconds before the close of the performance. Another way the spirit of the law was evaded, enabling the girl to move, and thus satisfying the demands of the audience, was by moving the props rather than the girls. Ruses such as a technically motionless nude girl holding on to a spinning rope were used. Since the rope was moving rather than the girl, authorities allowed it, even though the girl's body was displayed in motion. [5]

"We Never Closed": World War II

The theatre's famous motto "We Never Closed" (often humorously modified to "We Never Clothed") was a reference to the fact that the theatre remained open, apart from the compulsory closure that affected all theatres for 13 days (4 to 16 September) in 1939. Performances continued throughout the Second World War even at the height of the Blitz. The showgirls, cast members, and crew moved into the safety of the theatre's two underground floors during some of the worst air attacks, from 7 September 1940 to 11 May 1941.

Many of the Windmill's patrons were families and troops, as well as celebrities who came as Henderson's guests. These high society guests included Princesses Helena Victoria and Marie Louise (granddaughters of Queen Victoria). For a time, on the opening night of every new Windmill show, the Royal Box was always reserved for the Rt. Hon. George Lansbury, a member of His Majesty's Government. [6]

The theatre ran into the occasional problem with male patrons, but security guards were always on the lookout for improper behaviour. One of the more comical off-stage acts was the spectacle of the "Windmill Steeplechase" where, at the end of a show, patrons from the back rows would make a dash over the top of the seats to grab the front rows for the following show.

Postwar years

When Mrs Henderson died on 29 November 1944, aged 82, she left the Windmill to Van Damm. During his tenure, the Windmill was home to numerous famous comedians and actors who had their first real success there, including Jimmy Edwards, Harry Worth, Tony Hancock, Spike Milligan, Harry Secombe, Peter Sellers, Michael Bentine, George Martin, Bruce Forsyth, Arthur English, Tommy Cooper and Barry Cryer. Cryer was "a bottom of the bill" comic at the Windmill, while Forsyth performed as a juvenile performer — a superior post. A number of the most celebrated photographic pin-up models of the 1950s and early 1960s also did a stint as Windmill Girls, including June Palmer, Lyn Shaw, June Wilkinson, and Lorraine Burnett.

Van Damm ran the theatre until his death on 14 December 1960, aged approximately 71. He left the theatre to his daughter, rally driver Sheila Van Damm. [7] She struggled to keep it going, but by this time, London's Soho neighbourhood had become a seedier place. The Soho neighbourhood of the 1930s and 1940s had been a respectable place filled with shops and family restaurants. The Revudeville shows ran from 1932 to 1964, until the Windmill officially closed on 31 October 1964. [8]

Windmill Cinema

The theatre then changed hands and became the Windmill Cinema (with a casino incorporated in the building), having been bought by the Compton Cinema Group [9] run by Michael Klinger and Tony Tenser. [10] On 2 November 1964, the Windmill Cinema opened with the film Nude Las Vegas. The cinema became part of the Classic Cinema chain in May 1966. On 9 June 1974, the Windmill Cinema closed.

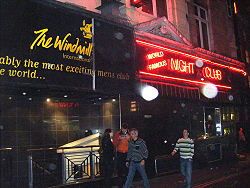

1974 to 2025: Multiple Changes

The cinema's lease was bought in February 1974 by nightclub and erotica entrepreneur Paul Raymond. [9] Raymond returned it to a venue for nude shows "à la Revuedeville but without the comic element". The first production at the now renamed Windmill Theatre was a play called Let's Get Laid, which opened on 2 September 1974, and starred Fiona Richmond and John Inman. A nude dance show called Rip-Off was the next production at the theatre; this show commenced on 10 May 1976. Paul Raymond re-introduced burlesque when he renamed the Windmill La Vie en Rose Show Bar and opened the venue as a supper club with a laser disco on 16 November 1982.

The venue became Paramount City in May 1986, a cabaret club managed for a short duration by Debbie Raymond, Paul Raymond's daughter. A period as a television studio followed – the Sky television programme Jameson Tonight was produced in the studio. In 1989, Big Bang performed their Arabic Circus Tour at the Windmill Theatre. Comedian Arthur Smith hosted a television show featuring comedians and music acts, simply called Paramount City, which ran on Saturday nights for two series on BBC One between 1990 and 1991.

In 1994, the former theatre part of the building was leased to Oscar Owide as a Wild West venue which became after a short time an erotic table-dancing club called The Windmill International, run by Oscar Owide and his son Daniel. [11] Until 2009, the Paul Raymond Organisation occupied the Piccadilly Buildings section of the building as their offices. A "gas or electricity explosion" occurred in the male toilets of the Windmill Club on 3 March 2017, causing damage to the adjacent pavement, and leading to a brief evacuation of the building and surrounding area. [12] Oscar Owide died in December 2017. A month later, the Windmill lost its licence because it had been found to have broken the "no touching" requirement between performers and clients. [13] [14]

In May 2021, it was announced that the Windmill would reopen as a 350-seat restaurant and bar, with a cabaret. [15]

2025 to present: Spearmint Rhino

In September 2025, Spearmint Rhino acquired the venue and renamed it Rhino Windmill. The club reopened in March 2026 as an adult entertainment venue, with a separate private members club called Shelter operating in the basement. [16]

This page is based on this

Wikipedia article Text is available under the

CC BY-SA 4.0 license; additional terms may apply.

Images, videos and audio are available under their respective licenses.