Related Research Articles

Yukon is the smallest and westernmost of Canada's three territories. It also is the second-least populated province or territory in Canada, with a population of 44,412 as of March 2023. Whitehorse, the territorial capital, is the largest settlement in any of the three territories.

The minister of Crown–Indigenous relations is a minister of the Crown in the Canadian Cabinet, one of two ministers who administer Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada (CIRNAC), the department of the Government of Canada which is responsible for administering the Indian Act and other legislation dealing with "Indians and lands reserved for the Indians" under subsection 91(24) of the Constitution Act, 1867. The minister is also more broadly responsible for overall relations between the federal government and First Nations, Métis, and Inuit.

In Canada, an Indian reserve is defined by the Indian Act as a "tract of land, the legal title to which is vested in Her Majesty, that has been set apart by Her Majesty for the use and benefit of a band." Reserves are areas set aside for First Nations, one of the major groupings of Indigenous peoples in Canada, after a contract with the Canadian state, and are not to be confused with indigenous peoples' claims to ancestral lands under Aboriginal title.

Crown–Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada is the department of the Government of Canada responsible for Canada's northern lands and territories, and one of two departments with responsibility for policies relating to Indigenous peoples in Canada.

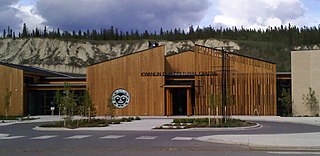

The Kwanlin Dün First Nation (KDFN) or Kwänlin Dän kwächʼǟn is located in and around Whitehorse in Yukon, Canada.

The Carcross/Tagish First Nation is a First Nation native to the Canadian territory of Yukon. Its original population centres were Carcross and Tagish, and Squanga, although many of its citizens also live in Whitehorse. The languages originally spoken by Carcross/Tagish people were Tagish and Tlingit.

The First Nation of Na-Cho Nyäk Dun is a First Nation band government in Yukon, Canada. Its main population centre is in Mayo, Yukon, but many of its members live across Canada and the United States. Members of the First Nation of Na-Cho Nyak Dun claim Gwich'in ancestry, located in north, and Dene ancestry, located in the east, along with their Northern Tutchone ancestry. The Na-cho Nyak Dun are the northernmost representatives of the Northern Tutchone language and culture.

The Ta'an Kwach'an Council or Ta'an Kwäch’än Council is a self-governing Indigenous government whose traditional territory is located around the Whitehorse and Lake Laberge area in Canada's Yukon Territory. It split from the Kwanlin Dün First Nation to negotiate a separate land claim. The language originally spoken by the Ta’an Kwäch’än was Southern Tutchone. The Ta’an Kwäch’än comprise people of Southern Tutchone, Tagish and Tlingit descent. Approximately 50 per cent of the Ta’an Kwäch’än citizens now live in Whitehorse, Yukon Territory, with the balance disbursed throughout the rest of Canada, in the United States of America, and abroad. The Ta'an Kwäch’än take their name from Tàa'an Män in the heart of their traditional territory - so they called themselves ″People from Lake Laberge″.

The Teslin Tlingit Council (TTC) is a First Nation band government in the central Yukon in Canada, located in Teslin, Yukon along the Alaska Highway and Teslin Lake. The language originally spoken by the Teslin Tlingit or Deisleen Ḵwáan is Tlingit. Together with the Taku River Tlingit or Áa Tlein Ḵwáan around Atlin Lake of the Taku River Tlingit First Nation in British Columbia, they comprise the Inland Tlingit.

The White River First Nation (WRFN) is a First Nation of Upper Tanana, Northern Tutchone, and Southern Tutchone peoples in the western Yukon Territory in Canada. Its main population centre is Beaver Creek, Yukon.

The Southern Tutchone are a First Nations people of the Athabaskan-speaking ethnolinguistic group living mainly in the southern Yukon in Canada. The Southern Tutchone language, traditionally spoken by the Southern Tutchone people, is a variety of the Tutchone language, part of the Athabaskan language family. Some linguists suggest that Northern and Southern Tutchone are distinct and separate languages.

The Nisga'a Final Agreement, also known as the Nisga'a Treaty, is a treaty that was settled between the Nisg̱a'a, the government of British Columbia, and the Government of Canada that was signed on 27 May 1998 and came into effect on May 11, 2000. As part of the settlement in the Nass River valley nearly 2,000 km2 (800 sq mi) of land was officially recognized as Nisg̱a'a, and a 300,000 cubic decametres (1.1×1010 cu ft) (approx. 240,000 acre-feet) water reservation was also created. Bear Glacier Provincial Park was also created as a result of this agreement. Thirty-one Nisga'a placenames in the territory became official names. The land-claim settlement was the first formal modern day comprehensive treaty in the province— the first signed by a First Nation in British Columbia since the Douglas Treaties in 1854 (pertaining to areas on Vancouver Island) and Treaty 8 in 1899 (pertaining to northeastern British Columbia). The agreement gives the Nisga'a control over their land, including the forestry and fishing resources contained in it.

Pimicikamak is an indigenous people in Canada. Pimicikamak is related to, but constitutionally, legally, historically and administratively distinct from, the Cross Lake First Nation which is a statutory creation that provides services on behalf of the Canadian Government. Pimicikamak government is based on self-determination and has a unique form.

The lands inhabited by indigenous peoples receive different treatments around the world. Many countries have specific legislation, definitions, nomenclature, objectives, etc., for such lands. To protect indigenous land rights, special rules are sometimes created to protect the areas they live in. In other cases, governments establish "reserves" with the intention of segregation. Some indigenous peoples live in places where their right to land is not recognised, or not effectively protected.

Indigenous or Aboriginal self-government refers to proposals to give governments representing the Indigenous peoples in Canada greater powers of government. These proposals range from giving Aboriginal governments powers similar to that of local governments in Canada to demands that Indigenous governments be recognized as sovereign, and capable of "nation-to-nation" negotiations as legal equals to the Crown, as well as many other variations.

Jim Boss was an entrepreneur and the chief of the Southern Tutchone Ta’an Kwäch’än for over 40 years. He is most known for having initiated the first Yukon land claim, in 1902. His leadership allowed the First Nations from the southern region of the Yukon to make the transition from a traditional way of life to a Euro-Canadian economy. In 2001, he was designated a Person of National Historic Significance.

The Indigenous peoples of Yukon are ethnic groups who, prior to European contact, occupied the former countries now collectively known as Yukon. While most First Nations in the Canadian territory are a part of the wider Dene Nation, there are Tlingit and Métis nations that blend into the wider spectrum of indigeneity across Canada. Traditionally hunter-gatherers, indigenous peoples and their associated nations retain close connections to the land, the rivers and the seasons of their respective countries or homelands. Their histories are recorded and passed down the generations through oral traditions. European contact and invasion brought many changes to the native cultures of Yukon including land loss and non-traditional governance and education. However, indigenous people in Yukon continue to foster their connections with the land in seasonal wage labour such as fishing and trapping. Today, indigenous groups aim to maintain and develop indigenous languages, traditional or culturally-appropriate forms of education, cultures, spiritualities and indigenous rights.

Adeline Kh'ayàdê Webberis the current commissioner of Yukon, appointed on 29 May 2023 A member of the Teslin Tlingit First Nation and Kukhhittan Clan. Born and raised in Whitehorse, Yukon, Webber is a leader, advocate, volunteer, important community member and elder. She has worked in the federal public service, and has been extensively involved with land claims, First Nation self-government agreements, and Indigenous women’s rights in the territory. As the founder and former President of the Whitehorse Aboriginal Women’s Circle and as the Yukon District Director for the Public Service Commission of Canada, Webber's continued work in employment and training for First Nations people has been implemented through several women’s leadership-training courses, as well as the Northern Careers Program. Webber had served as the Administrator of Yukon Territory.

The Gwichʼin Tribal Council is a First Nations organization representing the Gwichʼin people of northern Canada, owning approximately 23,884 square kilometres of land in Yukon and the Northwest Territories. It was created in 1992 with the final ratification of the Gwichʼin Comprehensive Land Claim Agreement with the Government of Canada. Negotiations to achieve a Final Agreement, and thus, Gwichʼin self-government, are ongoing.

The self-formation of political organizations of Indigenous peoples in Canada has been a constant process over many centuries.

References

- ↑ "The Journey to Yukon Self Government". thejourney.mappingtheway.ca. Retrieved 2016-08-25.

- ↑ "Executive Council Office". 14 May 2019.

- 1 2 3 "Building The Future: Yukon First Nation Self-Government." Building The Future: Yukon First Nation Self-Government. AANDC, 2008. Web. 01 Apr. 2013.

- 1 2 3 Horne, Marian C. "Canadian Parliamentary Review." RSS. N.p., 21 Mar. 2013. Web. 01 Apr. 2013.

- ↑ "Elder who helped start Yukon land claim process dies at 86". CBC News . 2013-05-02. Retrieved 2013-05-12.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Smith, Elijah. "Tomorrow." Together Today for Our Children Tomorrow. Brampton: Charters Publishing Company Limited, 1977

- ↑ Smith, Elijah. "Tomorrow." Together Today for Our Children Tomorrow. Brampton: Charters Publishing Company Limited, 1977. N. pag. Print.

- 1 2 3 "Our Agreements". Mapping the Way. 2016-06-02. Retrieved 2016-08-25.