Asaga | |

|---|---|

| Born | c. 800 CE |

| Occupation | poet |

| Period | Rashtrakuta literature |

| Genre | Jain literature |

| Notable works | Vardhaman Charitra (Sanskrit, c. 853); Karnataka Kumarasambhava Kavya (Kannada, about c.850) |

Asaga, was a 9th-century [1] Digambara Jain poet who wrote in Sanskrit and Kannada language. He is most known for his extant work in Sanskrit, the Vardhamana Charitra (Life of Vardhamana). This epic poem which runs into eighteen cantos was written in 853 CE. It is the earliest available Sanskrit biography of the last tirthankara of Jainism, Mahavira. In all, he authored at least eight works in Sanskrit. [2] In Kannada, none of his writings, including the Karnataka Kumarasambhava Kavya (an adaptation of Kalidas's epic poem Kumārasambhava ) that have been referenced by latter day poets (including Nagavarma II who seems to provide a few quotations from the epic poem in his Kavyavalokana [3] ) have survived. [4] [5] [6] [7] [8]

His writings are known to have influenced Kannada poet Sri Ponna, the famous court poet of Rashtrakuta King Krishna III, and other writers who wrote on the lives of Jain Tirthankaras. [9] Kesiraja, (authored Shabdamanidarpana in c. 1260 CE), a Kannada grammarian cites Asaga as an authoritative writer of his time and places him along with other masters of early Kannada poetry. [10]

| Kannada poets and writers in the Rashtrakuta Empire (753–973 CE) | |

| Amoghavarsha | 850 |

| Srivijaya | 850 |

| Asaga | 850 |

| Shivakotiacharya | 900 |

| Ravinagabhatta | 930 |

| Adikavi Pampa | 941 |

| Jainachandra | 950 |

| Sri Ponna | 950 |

| Rudrabhatta | 9th-10th c. |

| Kavi Rajaraja | 9th-10th c. |

| Gajanakusha | 10th century |

| Earlier Kannada poets and writers praised in Kavirajamarga | |

| Durvinita | 6th century |

| Vimala | Pre-850 |

| Nagarjuna | Pre-850 |

| Jayabodhi | Pre-850 |

| Udaya | Pre-850 |

| Kavisvara | Pre-850 |

| Pandita Chandra | Pre-850 |

| Lokapala | Pre-850 |

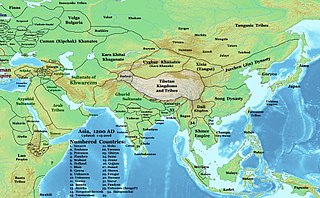

Asaga's name is considered an apbramsha form of the Sanskrit name Aśoka or Asanga. [7] A contemporary of Rashtrakuta King Amoghavarsha I (800–878 CE), Asaga lived in modern Karnataka and made important contributions to the corpus of Rashtrakuta literature created during their rule in southern and central India between the 8th and 10th centuries. [11] Like Kannada writer Gunavarma, Asaga earned fame despite having received no direct royal patronage. [9]

In his Vardhamacharita, Asaga mentions writing eight classics though the only one other work has survived, the Shanti purana in Sanskrit. [12] Asaga claims to have composed his writings in the city of Virala (Dharala), Coda Visaya ("Cola desa" or Coda lands), in the Kingdom of King Srinatha, who was perhaps a Rashtrakuta vassal. In Kaviprasastipradyani, the epilogue to the Shanti purana, Asaga claims he was born to Jain parents and names his three Jain teachers, including Bhavakirti. [5] [7] [13] [14]

Much of what is known about Asaga has come down from references to his works made by later-day writers and poets. Kannada poet Sri Ponna (c. 950), who used one of his narrative poems as a source, claims to be superior to Asaga. [15] Asaga's writings have been praised by later-day poets and writers, such as Kannada writer Jayakirti (Chchandanuphasana), who mentions Asaga's Karnataka Kumarasambhava Kavya. [16] Several of its verses have been quoted by later authors of Kannada literature such as Durgasimha, Nayasena and Jayakirti (a Kannada language theorist of the early 11th century) who refer to Asaga as the best writer of desi Kannada, which may be considered as "traditional" or "provincial" form of the language. [17] The Indologist A. K. Warder considers this unique because Asaga was also famous for classical Sanskrit. The 11th century Kannada grammarian Nagavarma II claimed Asaga to be an equal to Sri Ponna, and 12th century Kannada writer Brahmashiva refers to Asaga as Rajaka, a honorific that means "one among the greats" of Kannada literature. His writings appear to have been popular among later Kannada writers up to the decline of the Vijayanagara Empire in the 16th century. [15] Though his Kannada writings are deemed lost, his name is counted among noted poets of Kannada literature from that period, along with the likes of Gajaga, Aggala, Manasija, Srivardhadheva and Gunanandi. [18] The 10th century Apabhramsha poet Dhaval praised Asaga's writing Harivamsa-purana. [5]

Indian epic poetry is the epic poetry written in the Indian subcontinent, traditionally called Kavya. The Ramayana and the Mahabharata, which were originally composed in Sanskrit and later translated into many other Indian languages, and the Five Great Epics of Tamil literature and Sangam literature are some of the oldest surviving epic poems ever written.

Kannada literature is the corpus of written forms of the Kannada language, which is spoken mainly in the Indian state of Karnataka and written in the Kannada script.

Ranna, was one of the earliest and arguably one of the greatest poets of the Kannada language. His style of writing is often compared to that of Adikavi Pampa who wrote in the early 10th century. Together, Ranna, Adikavi Pampa and Sri Ponna are called "Three gems of ancient Kannada literature".

The Rashtrakutas were a royal Indian dynasty ruling large parts of the Indian subcontinent between the 6th and 10th centuries. The earliest known Rashtrakuta inscription is a 7th-century copper plate grant detailing their rule from Manapur, a city in Central or West India. Other ruling Rashtrakuta clans from the same period mentioned in inscriptions were the kings of Achalapur and the rulers of Kannauj. Several controversies exist regarding the origin of these early Rashtrakutas, their native homeland and their language.

Pampa, also referred to by the honorific Ādikavi, was a Kannada-language Jain poet whose works reflected his philosophical beliefs. He was a court poet of Vemulavada Chalukya king Arikesari II, who was a feudatory of the Rashtrakuta Emperor Krishna III. Pampa is best known for his epics Vikramārjuna Vijaya or Pampa Bharata, and the Ādi purāṇa, both written in the champu style around c. 939. These works served as the model for all future champu works in Kannada.

Ponna (c. 945) was a noted Kannada poet in the court of Rashtrakuta Emperor Krishna III. The emperor honoured Ponna with the title "emperor among poets" (Kavichakravarthi) for his domination of the Kannada literary circles of the time, and the title "imperial poet of two languages" for his command over Sanskrit as well. Ponna is often considered one among the "three gems of Kannada literature" for ushering it in full panoply. According to the scholar R. Narasimhacharya, Ponna is known to have claimed superiority over all the poets of the time. According to scholars Nilakanta Shastri and E.P. Rice, Ponna belonged to Vengi Vishaya in Kammanadu, Punganur, Andhra Pradesh, but later migrated to Manyakheta, the Rashtrakuta capital, after his conversion to Jainism.

Hoysala literature is the large body of literature in the Kannada and Sanskrit languages produced by the Hoysala Empire (1025–1343) in what is now southern India. The empire was established by Nripa Kama II, came into political prominence during the rule of King Vishnuvardhana (1108–1152), and declined gradually after its defeat by the Khalji dynasty invaders in 1311.

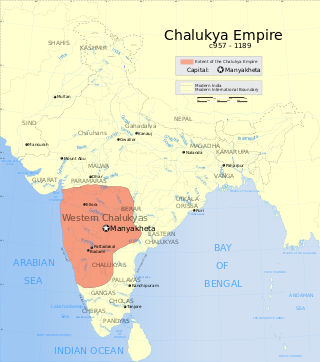

A large body of Western Chalukya literature in the Kannada language was produced during the reign of the Western Chalukya Empire in what is now southern India. This dynasty, which ruled most of the western Deccan in South India, is sometimes called the Kalyani Chalukya dynasty after its royal capital at Kalyani, and sometimes called the Later Chalukya dynasty for its theoretical relationship to the 6th-century Chalukya dynasty of Badami. For a brief period (1162–1183), the Kalachuris of Kalyani, a dynasty of kings who had earlier migrated to the Karnataka region from central India and served as vassals for several generations, exploited the growing weakness of their overlords and annexed the Kalyani. Around 1183, the last Chalukya scion, Someshvara IV, overthrew the Kalachuris to regain control of the royal city. But his efforts were in vain, as other prominent Chalukya vassals in the Deccan, the Hoysalas, the Kakatiyas and the Seunas destroyed the remnants of the Chalukya power.

Nāgavarma I (c. 990) was a noted Jain writer and poet in the Kannada language in the late 10th century. His two important works, both of which are extant, are Karnātaka Kādambari, a champu based romance novel and an adaptation of Bana's Sanskrit Kādambari, and Chandōmbudhi, the earliest available work on Kannada prosody which Nāgavarma I claims would command the respect even of poet Kalidasa. According to the scholars K.A. Nilakanta Shastri and R. Narasimhacharya, Nāgavarma I belonged to a migrant Brahmin family originally from Vengi. According to the modern Kannada poet and scholar Govinda Pai, Nāgavarma I lived from 950 CE to 1015 CE. So popular was Nāgavarma I's poetic skills that King Bhoja of Malwa presented him with horses, in appreciation of his poetic skills.

Nagavarma II was a Kannada language scholar and grammarian in the court of the Western Chalukya Empire that ruled from Basavakalyan, in modern Karnataka state, India. He was the earliest among the three most notable and authoritative grammarians of Old-Kannada language. Nagavarma II's reputation stems from his notable contributions to various genres of Kannada literature including prosody, rhetoric, poetics, grammar and vocabulary. According to the scholar R. Narasimhacharya, Nagavarma II is unique in all of ancient Kannada literature, in this aspect. His writings are available and are considered standard authorities for the study of Kannada language and its growth.

Rashtrakuta literature is the body of work created during the rule of the Rastrakutas of Manyakheta, a dynasty that ruled the southern and central parts of the Deccan, India between the 8th and 10th centuries. The period of their rule was an important time in the history of South Indian literature in general and Kannada literature in particular. This era was practically the end of classical Prakrit and Sanskrit writings when a whole wealth of topics were available to be written in Kannada. Some of Kannada's most famous poets graced the courts of the Rashtrakuta kings. Court poets and royalty created eminent works in Kannada and Sanskrit, that spanned such literary forms as prose, poetry, rhetoric, epics and grammar. Famous scholars even wrote on secular subjects such as mathematics. Rashtrakuta inscriptions were also written in expressive and poetic Kannada and Sanskrit, rather than plain documentary prose.

This is a chronology of the literature of Karnataka, India.

Western Ganga literature refers to a body of writings created during the rule of the Western Ganga Dynasty, a dynasty that ruled the region historically known as Gangavadi between the 4th and 11th centuries. The period of their rule was an important time in the history of South Indian literature in general and Kannada literature in particular, though many of the writings are deemed extinct. Some of the most famous poets of Kannada language graced the courts of the Ganga kings. Court poets and royalty created eminent works in Kannada language and Sanskrit language that spanned such literary forms as prose, poetry, Hindu epics, Jain Tirthankaras (saints) and elephant management.

Medieval Kannada literature covered a wide range of subjects and genres which can broadly be classified under the Jain, Virashaiva, Vaishnava and secular traditions. These include writings from the 7th century rise of the Badami Chalukya empire to the 16th century, coinciding with the decline of Vijayanagara Empire. The earliest known literary works until about the 12th century CE were mostly authored by the Jainas along with a few works by Virashaivas and Brahmins and hence this period is called the age of Jain literature,. The 13th century CE, to the 15th century CE, saw the emergence of numerous Virashaiva and Brahminical writers with a proportional decline in Jain literary works. Thereafter, Virashaiva and Brahmin writers have dominated the Kannada literary tradition. Some of the earliest metres used by Jain writers prior to 9th century include the chattana, bedande and the melvadu metres, writings in which have not been discovered but are known from references made to them in later centuries. Popular metres from the 9th century onwards when Kannada literature is available are the champu-kavyas or just champu, vachanasangatya, shatpadi, ragale, tripadi, and kavya.

Extinct Kannada literature is a body of literature of the Kannada language dating from the period preceding the first extant work, Kavirajamarga.

Raghavanka was a noted Kannada writer and a poet in the Hoysala court who flourished in the late 12th to early 13th century. Raghavanka is credited for popularizing the use of the native shatpadi metre in Kannada literature. Harishchandra Kavya, in shatpadi metre, is known to have been written with an interpretation unlike any other on the life of King Harishchandra is well known and is considered one of the important classics of Kannada language. He was a nephew and protégé of the noted Early 12-century Kannada poet Harihara. Although the shatpadi metre tradition existed in Kannada literature prior to Raghavanka, Raghavanka inspired the usage of the flexible metre for generations of poets, both Shaiva and Vaishnava to come.

Bhaṭṭākalaṅka Deva was the third and the last of the notable Kannada grammarians from the medieval period. In 1604 CE, he authored a comprehensive text on old-Kannada grammar called Karnāṭaka Śabdānuśāsana in 592 Sanskrit aphorisms with glossary and commentary. The work contains useful references to prior poets and writers of Kannada literature and is considered a valuable asset to the student of old-Kannada language. A native of South Canara and a student of the Haduvalli monastery, the Jain grammarian was learned in over six languages including Kannada, Sanskrit, Prakrit and Magadhi.

Palkuriki Somanatha was one of the most noted Telugu language writers of the 12th or 13th century. He was also an accomplished writer in the Kannada and Sanskrit languages and penned several classics in those languages. He was a Veerashaiva a follower of the 12th century social reformer Basava and his writings were primarily intended to propagate this faith. He was a well acclaimed Shaiva poet. The trio of Nanne Choda, Mallikarjuna Panditaradhya and Palkuriki Somanatha are referred as Śivakavitrayam. These trio along with Piduparthi poets and Yathavakkula Annamayya pioneered Veera Saiva movement in Andhra region.