Gasification is a process that converts biomass- or fossil fuel-based carbonaceous materials into gases, including as the largest fractions: nitrogen (N2), carbon monoxide (CO), hydrogen (H2), and carbon dioxide (CO2). This is achieved by reacting the feedstock material at high temperatures (typically >700 °C), without combustion, via controlling the amount of oxygen and/or steam present in the reaction. The resulting gas mixture is called syngas (from synthesis gas) or producer gas and is itself a fuel due to the flammability of the H2 and CO of which the gas is largely composed. Power can be derived from the subsequent combustion of the resultant gas, and is considered to be a source of renewable energy if the gasified compounds were obtained from biomass feedstock.

A fossil fuel power station is a thermal power station which burns a fossil fuel, such as coal or natural gas, to produce electricity. Fossil fuel power stations have machinery to convert the heat energy of combustion into mechanical energy, which then operates an electrical generator. The prime mover may be a steam turbine, a gas turbine or, in small plants, a reciprocating gas engine. All plants use the energy extracted from the expansion of a hot gas, either steam or combustion gases. Although different energy conversion methods exist, all thermal power station conversion methods have their efficiency limited by the Carnot efficiency and therefore produce waste heat.

Bioenergy is a type of renewable energy that is derived from plants and animal waste. The biomass that is used as input materials consists of recently living organisms, mainly plants. Thus, fossil fuels are not regarded as biomass under this definition. Types of biomass commonly used for bioenergy include wood, food crops such as corn, energy crops and waste from forests, yards, or farms.

Coal pollution mitigation, sometimes labeled as clean coal, is a series of systems and technologies that seek to mitigate health and environmental impact of burning coal for energy. Burning coal releases harmful substances, including mercury, lead, sulfur dioxide (SO2), nitrogen oxides (NOx), and carbon dioxide (CO2), contributing to air pollution, acid rain, and greenhouse gas emissions. Methods include flue-gas desulfurization, selective catalytic reduction, electrostatic precipitators, and fly ash reduction focusing on reducing the emissions of these harmful substances. These measures aim to reduce coal's impact on human health and the environment.

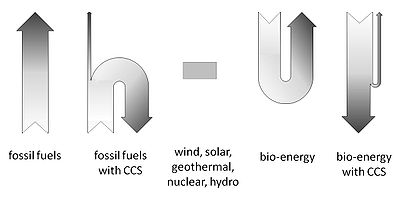

Carbon capture and storage (CCS) is a process in which a relatively pure stream of carbon dioxide (CO2) from industrial sources is separated, treated and transported to a long-term storage location. For example, the burning of fossil fuels or biomass results in a stream of CO2 that could be captured and stored by CCS. Usually the CO2 is captured from large point sources, such as a chemical plant or a bioenergy plant, and then stored in a suitable geological formation. The aim is to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and thus mitigate climate change. For example, CCS retrofits for existing power plants can be one of the ways to limit emissions from the electricity sector and meet the Paris Agreement goals.

An integrated gasification combined cycle (IGCC) is a technology using a high pressure gasifier to turn coal and other carbon based fuels into pressurized gas—synthesis gas (syngas). It can then remove impurities from the syngas prior to the electricity generation cycle. Some of these pollutants, such as sulfur, can be turned into re-usable byproducts through the Claus process. This results in lower emissions of sulfur dioxide, particulates, mercury, and in some cases carbon dioxide. With additional process equipment, a water-gas shift reaction can increase gasification efficiency and reduce carbon monoxide emissions by converting it to carbon dioxide. The resulting carbon dioxide from the shift reaction can be separated, compressed, and stored through sequestration. Excess heat from the primary combustion and syngas fired generation is then passed to a steam cycle, similar to a combined cycle gas turbine. This process results in improved thermodynamic efficiency, compared to conventional pulverized coal combustion.

Waste-to-energy (WtE) or energy-from-waste (EfW) is the process of generating energy in the form of electricity and/or heat from the primary treatment of waste, or the processing of waste into a fuel source. WtE is a form of energy recovery. Most WtE processes generate electricity and/or heat directly through combustion, or produce a combustible fuel commodity, such as methane, methanol, ethanol or synthetic fuels, often derived from the product syngas.

Biochar is the lightweight black residue, made of carbon and ashes, remaining after the pyrolysis of biomass, and is a form of charcoal. Biochar is defined by the International Biochar Initiative as "the solid material obtained from the thermochemical conversion of biomass in an oxygen-limited environment". Biochar is a stable solid that is rich in pyrogenic carbon and can endure in soil for thousands of years.

Biomass, in the context of energy production, is matter from recently living organisms which is used for bioenergy production. Examples include wood, wood residues, energy crops, agricultural residues including straw, and organic waste from industry and households. Wood and wood residues is the largest biomass energy source today. Wood can be used as a fuel directly or processed into pellet fuel or other forms of fuels. Other plants can also be used as fuel, for instance maize, switchgrass, miscanthus and bamboo. The main waste feedstocks are wood waste, agricultural waste, municipal solid waste, and manufacturing waste. Upgrading raw biomass to higher grade fuels can be achieved by different methods, broadly classified as thermal, chemical, or biochemical.

The Virgin Earth Challenge was a competition offering a $25 million prize for whoever could demonstrate a commercially viable design which results in the permanent removal of greenhouse gases out of the Earth's atmosphere to contribute materially in global warming avoidance. The prize was conceived by Richard Branson, and was announced in London on 9 February 2007 by Branson and former US Vice President Al Gore.

Second-generation biofuels, also known as advanced biofuels, are fuels that can be manufactured from various types of non-food biomass. Biomass in this context means plant materials and animal waste used especially as a source of fuel.

Carbon capture and storage (CCS) is a technology that can capture carbon dioxide CO2 emissions produced from fossil fuels in electricity, industrial processes which prevents CO2 from entering the atmosphere. Carbon capture and storage is also used to sequester CO2 filtered out of natural gas from certain natural gas fields. While typically the CO2 has no value after being stored, Enhanced Oil Recovery uses CO2 to increase yield from declining oil fields.

The milestones for carbon capture and storage show the lack of commercial scale development and implementation of CCS over the years since the first carbon tax was imposed.

Carbon dioxide removal (CDR) is a process in which carbon dioxide is removed from the atmosphere by deliberate human activities and durably stored in geological, terrestrial, or ocean reservoirs, or in products. This process is also known as carbon removal, greenhouse gas removal or negative emissions. CDR is more and more often integrated into climate policy, as an element of climate change mitigation strategies. Achieving net zero emissions will require first and foremost deep and sustained cuts in emissions, and then—in addition—the use of CDR. In the future, CDR may be able to counterbalance emissions that are technically difficult to eliminate, such as some agricultural and industrial emissions.

Microbial electrolysis carbon capture (MECC) is a carbon capture technique using microbial electrolysis cells during wastewater treatment. MECC results in net negative carbon emission wastewater treatment by removal of carbon dioxide (CO2) during the treatment process in the form of calcite (CaCO3), and production of profitable H2 gas.

Carbon capture and utilization (CCU) is the process of capturing carbon dioxide (CO2) from industrial processes and transporting it via pipelines to where one intends to use it in industrial processes.

Direct air capture (DAC) is the use of chemical or physical processes to extract carbon dioxide directly from the ambient air. If the extracted CO2 is then sequestered in safe long-term storage, the overall process will achieve carbon dioxide removal and be a "negative emissions technology" (NET).

Kenneth Karl Mikael Möllersten is a Swedish researcher. He holds a PhD in chemical engineering and an MSc in mechanical engineering, both from the Royal Institute of Technology (KTH), Stockholm, Sweden. Möllersten is a consultant and researcher at IVL Swedish Environmental Research Institute, was previously affiliated as a researcher with Mälardalen University and is currently affiliated with KTH.

Biochar carbon removal (BCR) is a negative emissions technology. It involves the production of biochar through pyrolysis of residual biomass and the subsequent application of the biochar in soils or durable materials. The carbon dioxide sequestered by the plants used for the biochar production is therewith stored for several hundreds of years, which creates carbon sinks.