Related Research Articles

Nirvana is a concept in Indian religions, the extinguishing of the passions which is the ultimate state of soteriological release and the liberation from duḥkha ('suffering') and saṃsāra, the cycle of birth and rebirth.

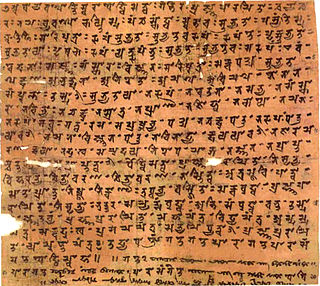

Sanskrit is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in South Asia after its predecessor languages had diffused there from the northwest in the late Bronze Age. Sanskrit is the sacred language of Hinduism, the language of classical Hindu philosophy, and of historical texts of Buddhism and Jainism. It was a link language in ancient and medieval South Asia, and upon transmission of Hindu and Buddhist culture to Southeast Asia, East Asia and Central Asia in the early medieval era, it became a language of religion and high culture, and of the political elites in some of these regions. As a result, Sanskrit had a lasting effect on the languages of South Asia, Southeast Asia and East Asia, especially in their formal and learned vocabularies.

Pāli is a Middle Indo-Aryan liturgical language on the Indian subcontinent. It is widely studied because it is the language of the Buddhist Pāli Canon or Tipiṭaka as well as the sacred language of Theravāda Buddhism.

A mantra or mantram is a sacred utterance, a numinous sound, a syllable, word or phonemes, or group of words believed by practitioners to have religious, magical or spiritual powers. Some mantras have a syntactic structure and a literal meaning, while others do not.

Magadha also called the Kingdom of Magadha or the Magadha Empire, was a kingdom and empire, and one of the sixteen Mahajanapadas, 'Great Kingdoms' of the Second Urbanization, based in southern Bihar in the eastern Ganges Plain, in Ancient India. Magadha was ruled by the Brihadratha dynasty, the Haryanka dynasty, the Shaishunaga dynasty, the Nanda dynasty, the Mauryan dynasty, the Shunga dynasty and the Kanva dynasty. It lost much of its territory after being defeated by the Satavahanas of Deccan in 28 BC and was reduced to a small principality around Pataliputra. Under the Mauryas, Magadha became a pan-Indian empire, covering large swaths of the Indian subcontinent and Afghanistan.

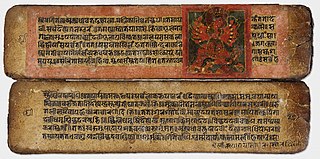

Buddhist texts are religious texts that belong to, or are associated with, Buddhism and its traditions. There is no single textual collection for all of Buddhism. Instead, there are three main Buddhist Canons: the Pāli Canon of the Theravāda tradition, the Chinese Buddhist Canon used in East Asian Buddhist tradition, and the Tibetan Buddhist Canon used in Indo-Tibetan Buddhism.

Sanskrit literature broadly comprises all literature in the Sanskrit language. This includes texts composed in the earliest attested descendant of the Proto-Indo-Aryan language known as Vedic Sanskrit, texts in Classical Sanskrit as well as some mixed and non-standard forms of Sanskrit. Literature in the older language begins with the composition of the Ṛg·veda between about 1500 and 1000 BCE, followed by other Vedic works right up to the time of the grammarian Pāṇini around 6th or 4th century BCE.

Mleccha is a Sanskrit term, referring to those of an incomprehensible speech, foreign or barbarous invaders as distinguished from Aryan Vedic tribes.

Ātman, attā or attan in Buddhism is the concept of self, and is found in Buddhist literature's discussion of the concept of non-self (Anatta). Most Buddhist traditions and texts reject the premise of a permanent, unchanging atman.

The word Bhagavan, also spelt as Bhagwan, an epithet within Indian religions used to denote figures of religious worship. In Hinduism it is used to signify a deity or an avatar, particularly for Krishna and Vishnu in Vaishnavism, Shiva in Shaivism and Durga or Adi Shakti in Shaktism. In Jainism the term refers to the Tirthankaras, and in Buddhism to the Buddha.

Āstika and Nāstika are concepts that have been used to classify the schools of Indian philosophy by modern scholars, as well as some Hindu, Buddhist and Jain texts. The various definitions for āstika and nāstika philosophies have been disputed since ancient times, and there is no consensus. One standard distinction, as within ancient- and medieval-era Sanskrit philosophical literature, is that āstika schools accept the Vedas, the ancient texts of India, as fundamentally authoritative, while the nāstika schools do not. However, a separate way of distinguishing the two terms has evolved in current Indian languages like Telugu, Hindi and Bengali, wherein āstika and its derivatives usually mean 'theist', and nāstika and its derivatives denote 'atheism'. Still, philosophical tradition maintains the earlier distinction, for example, in identifying the school of Sāṃkhya, which is non-theistic, as āstika (Veda-affirming) philosophy, though "God" is often used as an epithet for consciousness (purusha) within its doctrine. Similarly, though Buddhism is considered to be nāstika, Gautama Buddha is considered an avatar of the god Vishnu in some Hindu denominations. Due to its acceptance of the Vedas, āstika philosophy, in the original sense, is often equivalent to Hindu philosophy: philosophy that developed alongside the Hindu religion.

Buddhism, also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya, is an Indian religion and philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It is the world's fourth-largest religion, with over 520 million followers, known as Buddhists, who comprise seven percent of the global population. Buddhism originated in the eastern Gangetic plain as a śramaṇa–movement in the 5th century BCE, and gradually spread throughout much of Asia via the Silk Road.

The Middle Indo-Aryan languages are a historical group of languages of the Indo-Aryan family. They are the descendants of Old Indo-Aryan and the predecessors of the modern Indo-Aryan languages, such as Hindustani (Hindi-Urdu), Bengali and Punjabi.

Brahmā is a leading God (deva) and heavenly king in Buddhism. He is considered as a protector of teachings (dharmapala), and he is never depicted in early Buddhist texts as a creator god. In Buddhist tradition, it was the deity Brahma Sahampati who appeared before the Buddha and invited him to teach, once the Buddha attained enlightenment.

Buddhism and Hinduism have common origins in the culture of Ancient India. Buddhism arose in the Gangetic plains of Eastern India in the 5th century BCE during the Second Urbanisation. Hinduism developed as a fusion or synthesis of practices and ideas from the ancient Vedic religion and elements and deities from other local Indian traditions. This Hindu synthesis emerged after the Vedic period, between 500-200 BCE and c. 300 CE, in or after the period of the second urbanisation, and during the early classical period of Hinduism, when the Epics and the first Puranas were composed.

Kenneth Roy Norman was a British philologist at the University of Cambridge and a leading authority on Pali and other Middle Indo-Aryan languages.

The Pāli Canon is the standard collection of scriptures in the Theravada Buddhist tradition, as preserved in the Pāli language. It is the most complete extant early Buddhist canon. It derives mainly from the Tamrashatiya school.

Sanskrit Buddhist literature refers to Buddhist texts composed either in classical Sanskrit, in a register that has been called "Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit", or a mixture of these two. Several non-Mahāyāna Nikāyas appear to have kept their canons in Sanskrit, the most prominent being the Sarvāstivāda school. Many Mahāyāna Sūtras and śāstras also survive in Buddhistic Sanskrit or in standard Sanskrit.

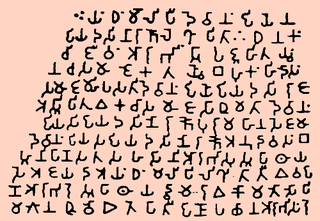

Lipi means 'writing, letters, alphabet', and contextually refers to scripts, the art or manner of writing, or in modified form such as lipī (लिपी) to painting, decorating or anointing a surface to express something.

Early Buddhist texts (EBTs), early Buddhist literature or early Buddhist discourses are parallel texts shared by the early Buddhist schools. The most widely studied EBT material are the first four Pali Nikayas, as well as the corresponding Chinese Āgamas. However, some scholars have also pointed out that some Vinaya material, like the Patimokkhas of the different Buddhist schools, as well as some material from the earliest Abhidharma texts could also be quite early.

References

- ↑ "Language Subtag Registry". IANA. 2021-03-05. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ↑ Hazra, Kanai Lal. Pāli Language and Literature; a systematic survey and historical study. D.K. Printworld Ltd., New Delhi, 1994, page 12.

- ↑ Hazra, page 5.

- 1 2 3 Edgerton, Franklin. The Prakrit Underlying Buddhistic Hybrid Sanskrit. Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, University of London, Vol. 8, No. 2/3, page 503.

- ↑ Edgerton, Franklin. The Prakrit Underlying Buddhistic Hybrid Sanskrit. Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, University of London, Vol. 8, No. 2/3, page 502. "Pāli is itself a middle-Indic dialect, and so resembles the protocanonical Prakrit in phonology and morphology much more closely than Sanskrit."

- ↑ Students' Britannica India. Popular Prakashan. 2000. pp. 145–. ISBN 978-0-85229-760-5.

- ↑ Hazra, pages 15, 19, 20.

- ↑ Jagajjyoti, Buddha Jayanti Annual, 1984, page 4, reprinted in K. R. Norman, Collected Papers, volume III, 1992, Pāli Text Society, page 37

- ↑ Edgerton, Franklin. The Prakrit Underlying Buddhistic Hybrid Sanskrit. Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, University of London, Vol. 8, No. 2/3, page 502.

- 1 2 T. Burrow (1965), The Sanskrit language, p. 61, ISBN 978-81-208-1767-8

- ↑ Edgerton, Franklin. The Prakrit Underlying Buddhistic Hybrid Sanskrit. Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, University of London, Vol. 8, No. 2/3, page 503. Available on JSTOR here.

- ↑ Edgerton, Franklin. The Prakrit Underlying Buddhistic Hybrid Sanskrit. Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, University of London, Vol. 8, No. 2/3, pages 503-505.

- ↑ Edgerton, Franklin. The Prakrit Underlying Buddhistic Hybrid Sanskrit. Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, University of London, Vol. 8, No. 2/3, page 504.

- ↑ Macmillan Encyclopedia of Buddhism (Volume One), page 154

- ↑ Paul J. Griffiths, Journal of the Pāli Text Society, Volume XXIX, page 102