Alija Izetbegović was a Bosnian politician, lawyer, Islamic philosopher and author, who in 1992 became the first president of the Presidency of the newly independent Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

The Party of Democratic Action is a Bosniak nationalist, conservative political party in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

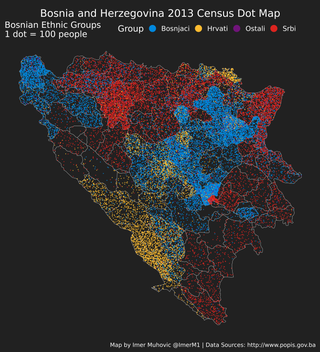

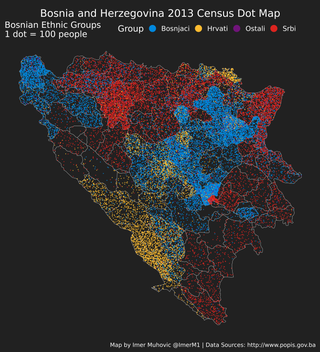

More than 96% of population of Bosnia and Herzegovina belongs to one of its three autochthonous constituent peoples : Bosniaks, Serbs and Croats. The term constituent refers to the fact that these three ethnic groups are explicitly mentioned in the constitution, and that none of them can be considered a minority or immigrant. The most easily recognisable feature that distinguishes the three ethnic groups is their religion, with Bosniaks predominantly Muslim, Serbs predominantly Eastern Orthodox, and Croats Catholic.

"Muslims" is a designation for the ethnoreligious group of Serbo-Croatian-speaking Muslims and people of Muslim heritage, inhabiting mostly the territory of the former Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. The term, adopted in the 1971 Constitution of Yugoslavia, groups together a number of distinct South Slavic communities of Islamic ethnocultural tradition. Prior to 1993, a vast majority of present-day Bosniaks self-identified as ethnic Muslims, along with some smaller groups of different ethnicity, such as Gorani and Torbeši. This designation did not include Yugoslav non-Slavic Muslims, such as Turks, some Romani people and majority of Albanians.

Islam is the second-largest religion in Europe after Christianity. Although the majority of Muslim communities in Western Europe formed recently, there are centuries-old Muslim communities in the Balkans, Caucasus, Crimea, and Volga region. The term "Muslim Europe" is used to refer to the Muslim-majority countries in the Balkans and parts of countries in Eastern Europe with sizable Muslim minorities that constitute large populations of indigenous European Muslims, although the majority are secular.

Islam in Montenegro refers to adherents, communities and religious institutions of Islam in Montenegro. It is the second largest religion in the country, after Christianity. According to the 2011 census, Montenegro's 118,477 Muslims make up 20% of the total population. Montenegro's Muslims belong mostly to the Sunni branch. According to the estimate by the Pew Research Center, Muslims have a population of 130,000 (20.3%) as of 2020.

Bosniaks are a mainly-muslim South Slavic ethnic group, native to the region of Bosnia and the region of Sandžak. The term Bosniaks was re-instated in 1993 after decades of suppression in the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. The Bosniak Assembly adopted the ethnonym to replace "Bosnian Muslims." Scholars believe that the move was partly motivated by a desire to distinguish the Bosniaks from the fabricated and imposed term Muslim to describe their nationality in the former Yugoslavia. These scholars contend that the Bosniaks are distinguishable from comparable groups due to a collective identity based on a shared environment, cultural practices and experiences.

Muslims in North Macedonia represent just under one-third of the nation's total population according to the 2021 census, making Islam the second most widely professed religion in the country. Muslims in North Macedonia follow Sunni Islam of the Hanafi madhhab. Some northwestern and western regions of the country have Muslim majorities. A large majority of all the Muslims in the country are ethnic Albanians, with the rest being primarily Turks, Romani, Bosniaks or Torbeš.

Croatia is a predominantly Christian country, with Islam being a minority faith. It is followed by 1.3% of the country's population according to the 2021 census. Islam was first introduced to Croatia by the Ottoman Empire during the Croatian–Ottoman Wars that lasted from the 15th to 16th century. During this period some parts of the Croatian Kingdom were occupied which resulted in some Croats converting to Islam, some after being taken prisoners of war, some through the devşirme system. Nonetheless, Croats strongly fought against the Turks during these few centuries which resulted in the fact that the westernmost border of the Ottoman Empire in Europe became entrenched on the Croatian soil. In 1519, Croatia was called the Antemurale Christianitatis by Pope Leo X.

European Islam is a hypothesized new branch of Islam that historically originated and developed among the European peoples of the Balkans and parts of countries in Eastern Europe with sizable Muslim minorities which constitute of large populations of European Muslims, alongside Muslim populations of Albanians, Bosniaks, Greeks, Cretan Turks, Vallahades, Turkish Cypriots, Romani, Balkan Turks, Torbesh, Gorani, Pomaks, Yörüks, Volga Tatars, Crimean Tatars, and Megleno-Romanians from Notia today living in Turkey, although the majority are secular.

The Islamic Declaration is an essay written by Alija Izetbegović (1925–2003), republished in 1990 in Sarajevo, SR Bosnia and Herzegovina, SFR Yugoslavia. It presents his views on Islam and modernization. The treatise attempts to reconcile Western-style progress with Islamic tradition and issues a call for "Islamic renewal". The work was later used against Izetbegović and other pan-Islamists in a 1983 trial in Sarajevo, which resulted in him being sentenced to 14 years' imprisonment. He was released after two years.

The most widely professed religion in Bosnia and Herzegovina is Islam and the second biggest religion is Christianity. Nearly all the Muslims of Bosnia are followers of the Sunni denomination of Islam; the majority of Sunnis follow the Hanafi legal school of thought (fiqh) and Maturidi theological school of thought (kalām). Bosniaks are generally associated with Islam, Bosnian Croats with the Roman Catholic Church, and Bosnian Serbs with the Serbian Orthodox Church. The State Constitution of Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) and the entity Constitutions of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Republika Srpska provide for freedom of religion, and the Government generally respects this right in ethnically integrated areas or in areas where government officials are of the majority religion; the state-level Law on Religious Freedom also provides comprehensive rights to religious communities. However, local authorities sometimes restricted the right to worship of adherents of religious groups in areas where such persons are in the minority.

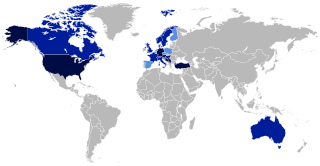

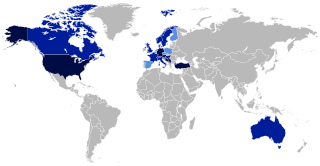

The Bosniaks are a South Slavic ethnic group native to the Southeast European historical region of Bosnia, which is today part of Bosnia and Herzegovina, who share a common Bosnian ancestry, culture, history and language. They primarily live in Bosnia, Serbia, Montenegro, Croatia, Kosovo as well as in Austria, Germany, Turkey and Sweden. They also constitute a significant diaspora with several communities across Europe, the Americas and Oceania.

Mehmed Handžić was a Bosnian Islamic scholar, theologian and politician. Handžić was the leader of the Islamic revivalist movement in Bosnia and the founder of the religious association El-Hidaje. He was one of the authors of the Resolution of Sarajevo Muslims and the chairman of the Committee of National Salvation.

Bosnians are people native to the country of Bosnia and Herzegovina, especially the historical region of Bosnia. As a common demonym, the term Bosnians refers to all inhabitants/citizens of the country, regardless of any ethnic, cultural or religious affiliation. It can also be used as a designation for anyone who is descended from the region of Bosnia. Also, a Bosnian can be anyone who holds citizenship of the state of Bosnia and Herzegovina and thus is largely synonymous with the all-encompassing national demonym Bosnians and Herzegovinians.

Bosnia and Herzegovina–Turkey relations are the bilateral relations between Bosnia-Herzegovina and Turkey. Bosnia and Herzegovina is a southeast European country, while Turkey is a transcontinental country with a small European part on the Balkan peninsula around Istanbul. Diplomatic relations between the two countries started on 29 August 1992. Bosnia and Herzegovina has one embassy in Ankara and two consulates in Istanbul and Izmir, while Turkey has one embassy in Sarajevo and one consulate in Mostar. The two countries enjoy very warm diplomatic relations, due to historical and cultural ties dating back to the 15th century. There is a large population of Bosniaks in Turkey and a smaller community of Turks in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The Istanbul quarter of Yenibosna is named in honour of the Bosnian community that has settled there since Ottoman times. Reflecting the close ties between the two nations, Bosnians and Turks are free to travel to each other's countries using only their national identification cards, without the need for a passport. Turkey gives full support to Bosnia and Herzegovina's NATO membership.

Croat Muslims are Muslims of Croat ethnic origin. They consist primarily of the descendants of the Ottoman-era Croats.

Serb Muslims or Serb Mohammedans, also referred to as Čitaci, are ethnic Serbs who are Muslims by their religious affiliation.

The Islamization of Albania occurred as a result of the Ottoman conquest of the region beginning in 1385. The Ottomans through their administration and military brought Islam to Albania through various policies and tax incentives, trade networks and transnational religious links. In the first few centuries of Ottoman rule, the spread of Islam in Albania was slow and mainly intensified during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries due in part to greater Ottoman societal and military integration, geo-political factors and collapse of church structures. It was one of the most significant developments in Albanian history as Albanians in Albania went from being a largely Christian population to one that is mainly Sunni Muslim, while retaining significant ethnic Albanian Christian minorities in certain regions. The resulting situation where Sunni Islam was the largest faith in the Albanian ethnolinguistic area, but other faiths were also present in a regional patchwork, played a major influence in shaping the political development of Albania in the late Ottoman period. Apart from religious changes, conversion to Islam also brought about other social and cultural transformations that have shaped and influenced Albanians and Albanian culture.

Gunja Mosque is the oldest active mosque in Croatia built in 1969. It is located in the village of Gunja in the Croatian part of Syrmia.