Spanish cuisine consists of the traditions and practices of Spanish cooking. It features considerable regional diversity, with important differences between the traditions of each part of Spain.

Turkish cuisine is the cuisine of Turkey and the Turkish diaspora. It is largely the heritage of Ottoman cuisine, which can be described as a fusion and refinement of Mediterranean, Balkan, Middle Eastern, Central Asian and Eastern European cuisines. Turkish cuisine has in turn influenced those and other neighbouring cuisines, including those of Southeast Europe (Balkans), Central Europe, and Western Europe. The Ottomans fused various culinary traditions of their realm taking influences from and influencing Mesopotamian cuisine, Greek cuisine, Levantine cuisine, Egyptian cuisine, Balkan cuisine, along with traditional Turkic elements from Central Asia, creating a vast array of specialities. Turkish cuisine also includes dishes invented in the Ottoman palace kitchen.

Hungarian or Magyar cuisine is the cuisine characteristic of the nation of Hungary, and its primary ethnic group, the Magyars. Hungarian cuisine has been described as being the spiciest cuisine in Europe. This can largely be attributed to the use of their piquant native spice, Hungarian paprika, in many of their dishes. A mild version of the spice, Hungarian sweet paprika, is commonly used as an alternative. Traditional Hungarian dishes are primarily based on meats, seasonal vegetables, fruits, bread, and dairy products.

Russian cuisine is a collection of the different dishes and cooking traditions of the Russian people as well as a list of culinary products popular in Russia, with most names being known since pre-Soviet times, coming from all kinds of social circles.

Romanian cuisine is a diverse blend of different dishes from several traditions with which it has come into contact, but it also maintains its own character. It has been mainly influenced by Turkish and a series of European cuisines in particular from the Balkans, or Hungarian cuisine as well as culinary elements stemming from the cuisines of Central Europe.

Jewish cuisine refers to the worldwide cooking traditions of the Jewish people. During its evolution over the course of many centuries, it has been shaped by Jewish dietary laws (kashrut), Jewish festivals and holidays, and traditions centred around Shabbat. Jewish cuisine is influenced by the economics, agriculture, and culinary traditions of the many countries where Jewish communities have settled and varies widely throughout the entire world.

Kibbeh is a family of dishes based on spiced ground meat, onions, and grain, popular in Middle Eastern cuisine.

Arab cuisine is the cuisine of the Arabs, defined as the various regional cuisines spanning the Arab world, from the Maghreb to the Fertile Crescent and the Arabian Peninsula. These cuisines are centuries old and reflect the culture of trading in baharat (spices), herbs, and foods. The regions have many similarities, but also unique traditions. They have also been influenced by climate, cultivation, and mutual commerce.

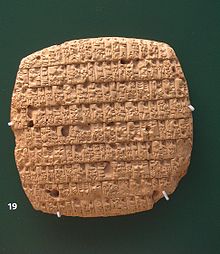

Iraqi cuisine or Mesopotamian cuisine is a Middle Eastern cuisine that has its origins from Sumerians, Akkadians, Babylonians, Assyrians and the other groups of the region.

Czech cuisine has both influenced and been influenced by the cuisines of surrounding countries and nations. Many of the cakes and pastries that are popular in Central Europe originated within the Czech lands. Contemporary Czech cuisine is more meat-based than in previous periods; the current abundance of farmable meat has enriched its presence in regional cuisine. Traditionally, meat has been reserved for once-weekly consumption, typically on weekends.

Sofrito, sofregit, soffritto, or refogado is a basic preparation in Mediterranean, Latin American, Spanish, Italian and Portuguese cooking. It typically consists of aromatic ingredients cut into small pieces and sautéed or braised in cooking oil for a long period of time over a low heat.

Assyrian cuisine is the cuisine of the indigenous ethnic Assyrian people, Eastern Aramaic-speaking Syriac Christians of Iraq, northeastern Syria, northwestern Iran and southeastern Turkey. Assyrian cuisine is primarily identical to Iraqi/Mesopotamian cuisine, as well as being very similar to other Middle Eastern and Caucasian cuisines, as well as Greek cuisine, Levantine cuisine, Turkish cuisine, Iranian cuisine, Israeli cuisine, and Armenian cuisine, with most dishes being similar to the cuisines of the area in which those Assyrians live/originate from. It is rich in grains such as barley, meat, tomato, herbs, spices, cheese, and potato as well as herbs, fermented dairy products, and pickles.

Yemeni cuisine is distinct from the wider Middle Eastern cuisines, but with a degree of regional variation. Although some foreign influences are evident in some regions of the country, the Yemeni kitchen is based on similar foundations across the country.

Armenian cuisine includes the foods and cooking techniques of the Armenian people and traditional Armenian foods and dishes. The cuisine reflects the history and geography where Armenians have lived as well as sharing outside influences from European and Levantine cuisines. The cuisine also reflects the traditional crops and animals grown and raised in Armenian-populated areas.

Sephardic Jewish cuisine is an assortment of cooking traditions that developed among the Sephardi Jews.

More or less distinct areas in medieval Europe where certain foodstuffs dominated can be discerned. In the British Isles, northern France, the Low Countries, the northern German-speaking areas, Scandinavia and the Baltic the climate was generally too harsh for the cultivation of grapes and olives. In the south, wine was the common drink for both rich and poor alike while beer was the commoner's drink in the north and wine an expensive import. Citrus fruits and pomegranates were common around the Mediterranean. Dried figs and dates occurred quite frequently in the north, but were used rather sparingly in cooking.

Romani cuisine is the cuisine of the ethnic Romani people. There is no specific "Roma cuisine"; it varies and is culinarily influenced by the respective countries where they have often lived for centuries. Hence, it is influenced by European cuisine even though the Romani people originated from the Indian subcontinent. Their cookery incorporates Indian and South Asian influences, but is also very similar to Hungarian cuisine. The many cultures that the Roma contacted are reflected in their cooking, resulting in many different cuisines. Some of these cultures are Middle European, Germany, Great Britain, and Spain. The cuisine of Muslim Romani people is also influenced by Balkan cuisine and Turkish cuisine.

Middle Eastern cuisine or West Asian cuisine includes Arab, Armenian, Assyrian, Azerbaijani, Cypriot, Egyptian, Georgian, Iranian, Iraqi, Israeli/Jewish, Kurdish, Lebanese, Palestinian and Turkish cuisines. Common ingredients include olives and olive oil, pitas, honey, sesame seeds, dates, sumac, chickpeas, mint, rice and parsley, and popular dishes include kebabs, dolmas, falafel, baklava, yogurt, doner kebab, shawarma and mulukhiyah.

Ashkenazi Jewish cuisine is an assortment of cooking traditions that was developed by the Ashkenazi Jews of Central, Eastern and Northern Europe, and their descendants, particularly in the United States and other Western countries.