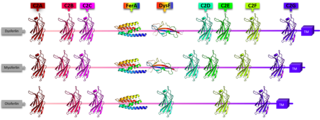

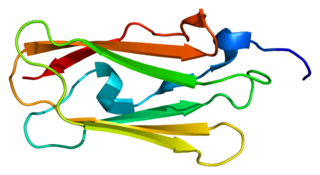

Titin is a protein that in humans is encoded by the TTN gene. Titin is a giant protein, greater than 1 µm in length, that functions as a molecular spring that is responsible for the passive elasticity of muscle. It comprises 244 individually folded protein domains connected by unstructured peptide sequences. These domains unfold when the protein is stretched and refold when the tension is removed.

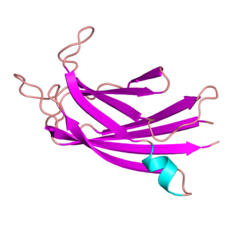

In molecular biology, caveolins are a family of integral membrane proteins that are the principal components of caveolae membranes and involved in receptor-independent endocytosis. Caveolins may act as scaffolding proteins within caveolar membranes by compartmentalizing and concentrating signaling molecules. They also induce positive (inward) membrane curvature by way of oligomerization, and hairpin insertion. Various classes of signaling molecules, including G-protein subunits, receptor and non-receptor tyrosine kinases, endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), and small GTPases, bind Cav-1 through its 'caveolin-scaffolding domain'.

Caveolin-3 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the CAV3 gene. Alternative splicing has been identified for this locus, with inclusion or exclusion of a differentially spliced intron. In addition, transcripts utilize multiple polyA sites and contain two potential translation initiation sites.

Distal myopathy is a group of rare genetic disorders that cause muscle damage and weakness, predominantly in the hands and/or feet. Mutation of many different genes can be causative. Many types involve dysferlin.

Emerin is a protein that in humans is encoded by the EMD gene, also known as the STA gene. Emerin, together with LEMD3, is a LEM domain-containing integral protein of the inner nuclear membrane in vertebrates. Emerin is highly expressed in cardiac and skeletal muscle. In cardiac muscle, emerin localizes to adherens junctions within intercalated discs where it appears to function in mechanotransduction of cellular strain and in beta-catenin signaling. Mutations in emerin cause X-linked recessive Emery–Dreifuss muscular dystrophy, cardiac conduction abnormalities and dilated cardiomyopathy.

Laminopathies are a group of rare genetic disorders caused by mutations in genes encoding proteins of the nuclear lamina. They are included in the more generic term nuclear envelopathies that was coined in 2000 for diseases associated with defects of the nuclear envelope. Since the first reports of laminopathies in the late 1990s, increased research efforts have started to uncover the vital role of nuclear envelope proteins in cell and tissue integrity in animals.

SK3 also known as KCa2.3 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the KCNN3 gene.

Fukutin is a eukaryotic protein necessary for the maintenance of muscle integrity, cortical histogenesis, and normal ocular development. Mutations in the fukutin gene have been shown to result in Fukuyama congenital muscular dystrophy (FCMD) characterised by brain malformation - one of the most common autosomal-recessive disorders in Japan. In humans this protein is encoded by the FCMD gene, located on chromosome 9q31. Human fukutin exhibits a length of 461 amino acids and a predicted molecular mass of 53.7 kDa.

Four and a half LIM domains protein 1 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the FHL1 gene.

Calpain-3 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the CAPN3 gene.

Filamin-C (FLN-C) also known as actin-binding-like protein (ABPL) or filamin-2 (FLN2) is a protein that in humans is encoded by the FLNC gene. Filamin-C is mainly expressed in cardiac and skeletal muscles, and functions at Z-discs and in subsarcolemmal regions.

Sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase 1 (SERCA1) also known as Calcium pump 1, is an enzyme that in humans is encoded by the ATP2A1 gene.

Alpha-7 integrin is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ITGA7 gene. Alpha-7 integrin is critical for modulating cell-matrix interactions. Alpha-7 integrin is highly expressed in cardiac muscle, skeletal muscle and smooth muscle cells, and localizes to Z-disc and costamere structures. Mutations in ITGA7 have been associated with congenital myopathies and noncompaction cardiomyopathy, and altered expression levels of alpha-7 integrin have been identified in various forms of muscular dystrophy.

Delta-sarcoglycan is a protein that in humans is encoded by the SGCD gene.

Alpha-sarcoglycan is a protein that in humans is encoded by the SGCA gene.

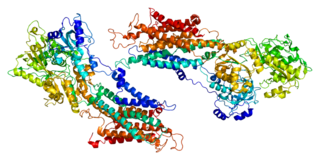

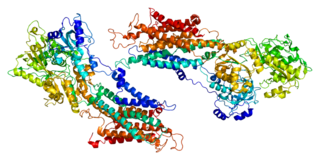

Ryanodine receptor 1 (RYR-1) also known as skeletal muscle calcium release channel or skeletal muscle-type ryanodine receptor is one of a class of ryanodine receptors and a protein found primarily in skeletal muscle. In humans, it is encoded by the RYR1 gene.

Collagen VI (ColVI) is a type of collagen primarily associated with the extracellular matrix of skeletal muscle. ColVI maintains regularity in muscle function and stabilizes the cell membrane. It is synthesized by a complex, multistep pathway that leads to the formation of a unique network of linked microfilaments located in the extracellular matrix (ECM). ColVI plays a vital role in numerous cell types, including chondrocytes, neurons, myocytes, fibroblasts, and cardiomyocytes. ColVI molecules are made up of three alpha chains: α1(VI), α2(VI), and α3(VI). It is encoded by 6 genes: COL6A1, COL6A2, COL6A3, COL6A4, COL6A5, and COL6A6. The chain lengths of α1(VI) and α2(VI) are about 1,000 amino acids. The chain length of α3(VI) is roughly a third larger than those of α1(VI) and α2(VI), and it consists of several spliced variants within the range of 2,500 to 3,100 amino acids.

Myogenic factor 6 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the MYF6 gene. This gene is also known in the biomedical literature as MRF4 and herculin. MYF6 is a myogenic regulatory factor (MRF) involved in the process known as myogenesis.

Anoctamin 5 (ANO5) is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ANO5 gene.

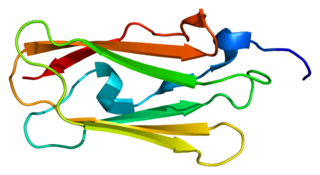

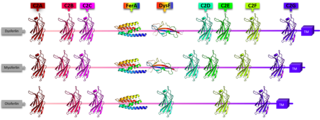

Ferlins are an ancient protein family involved in vesicle fusion and membrane trafficking. Ferlins are distinguished by their multiple tandem C2 domains, and sometimes a FerA and a DysF domain. Mutations in ferlins can cause human diseases such as muscular dystrophy and deafness. Abnormalities in expression of myoferlin, a human ferlin protein, is also directly associated with higher mortality rate and tumor recurrence in several types of cancer, including pancreatic, colorectal, breast, cervical, stomach, ovarian, cervical, thyroid, endometrial, and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. In other animals, ferlin mutations can cause infertility.