Related Research Articles

Bioethics is both a field of study and professional practice, interested in ethical issues related to health, including those emerging from advances in biology, medicine, and technologies. It proposes the discussion about moral discernment in society and it is often related to medical policy and practice, but also to broader questions as environment, well-being and public health. Bioethics is concerned with the ethical questions that arise in the relationships among life sciences, biotechnology, medicine, politics, law, theology and philosophy. It includes the study of values relating to primary care, other branches of medicine, ethical education in science, animal, and environmental ethics, and public health.

Utilitarian bioethics refers to the branch of bioethics that incorporates principles of utilitarianism to directing practices and resources where they will have the most usefulness and highest likelihood to produce happiness, in regards to medicine, health, and medical or biological research.

Nick Bostrom is a Swedish philosopher at the University of Oxford known for his work on existential risk, the anthropic principle, human enhancement ethics, whole brain emulation, superintelligence risks, and the reversal test. He is the founding director of the Future of Humanity Institute at Oxford University.

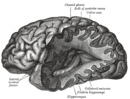

In philosophy and neuroscience, neuroethics is the study of both the ethics of neuroscience and the neuroscience of ethics. The ethics of neuroscience concerns the ethical, legal and social impact of neuroscience, including the ways in which neurotechnology can be used to predict or alter human behavior and "the implications of our mechanistic understanding of brain function for society... integrating neuroscientific knowledge with ethical and social thought".

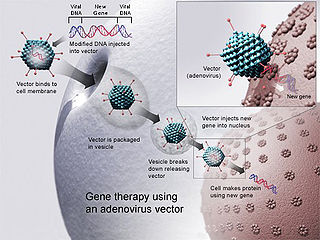

Human genetic enhancement or human genetic engineering refers to human enhancement by means of a genetic modification. This could be done in order to cure diseases, prevent the possibility of getting a particular disease, to improve athlete performance in sporting events, or to change physical appearance, metabolism, and even improve physical capabilities and mental faculties such as memory and intelligence. These genetic enhancements may or may not be done in such a way that the change is heritable.

Solidarity or solidarism is an awareness of shared interests, objectives, standards, and sympathies creating a psychological sense of unity of groups or classes. Solidarity does not reject individuals and sees individuals as the basis of society. It refers to the ties in a society that bind people together as one. The term is generally employed in sociology and the other social sciences as well as in philosophy and bioethics. It is a significant concept in Catholic social teaching and in Christian democratic political ideology.

Julian Savulescu is an Australian philosopher and bioethicist of Romanian origins. He is Chen Su Lan Centennial Professor in Medical Ethics and director of the Centre for Biomedical Ethics at National University of Singapore. He was previously Uehiro Chair in Practical Ethics at the University of Oxford, Fellow of St Cross College, Oxford, director of the Oxford Uehiro Centre for Practical Ethics, and co-director of the Wellcome Centre for Ethics and Humanities. He is visiting professorial fellow in Biomedical Ethics at the Murdoch Children's Research Institute in Australia, and distinguished visiting professor in law at Melbourne University since 2017. He directs the Biomedical Ethics Research Group and is a member of the Centre for Ethics of Pediatric Genomics in Australia. He is a former editor and current board member of the Journal of Medical Ethics, which is ranked as the No.2 journal in bioethics worldwide by Google Scholar Metrics, as of 2022. In addition to his background in applied ethics and philosophy, he also has a background in medicine and neuroscience and completed his MBBS (Hons) and BMedSc at Monash University, graduating top of his class with 18 of 19 final year prizes in Medicine. He edits the Oxford University Press book series, the Uehiro Series in Practical Ethics.

Human nature comprises the fundamental dispositions and characteristics—including ways of thinking, feeling, and acting—that humans are said to have naturally. The term is often used to denote the essence of humankind, or what it 'means' to be human. This usage has proven to be controversial in that there is dispute as to whether or not such an essence actually exists.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to ethics.

Vojin B. Rakic is a Serbian philosopher and political scientist. He publishes in English, but also in Serbian. He has a PhD in political science from Rutgers University in the United States. His publications on ethics, bioethics, Kant, and cosmopolitan justice are considered as influential writings in the international academic arena, as can be read in the references to Rakić`s works, the endorsements of his two latest books, as well as in the open letter of support for Rakić that has been signed by dozens of the world`s most reputed (bio)ethicists and philosophers, in which they state their opinion about him.

The reversal test is a heuristic designed to spot and eliminate status quo bias, an emotional bias irrationally favouring the current state of affairs. The test is applicable to the evaluation of any decision involving a potential deviation from the status quo along some continuous dimension. The reversal test was introduced in the context of the bioethics of human enhancement by Nick Bostrom and Toby Ord.

"After-birth abortion: why should the baby live?" is a controversial article published by Francesca Minerva and Alberto Giubilini in Journal of Medical Ethics in 2013 arguing to call child euthanasia "after-birth abortion" and highlighting similarities between abortion and euthanasia. The article attracted media attention and several scholarly critiques. According to Michael Tooley, "Very few philosophical publications, however, have evoked either more widespread attention, or emotionally more heated reactions, than this article has."

David DeGrazia is an American moral philosopher specializing in bioethics and animal ethics. He is Professor of Philosophy at George Washington University, where he has taught since 1989, and the author or editor of several books on ethics, including Taking Animals Seriously: Mental Life and Moral Status (1996), Human Identity and Bioethics (2005), and Creation Ethics: Reproduction, Genetics, and Quality of Life (2012).

Alasdair Cochrane is a British political theorist and ethicist who is currently Professor of Political Theory in the Department of Politics and International Relations at the University of Sheffield. He is known for his work on animal rights from the perspective of political theory, which is the subject of his two books: An Introduction to Animals and Political Theory and Animal Rights Without Liberation. His third book, Sentientist Politics, was published by Oxford University Press in 2018. He is a founding member of the Centre for Animals and Social Justice, a UK-based think tank focused on furthering the social and political status of nonhuman animals. He joined the Department at Sheffield in 2012, having previously been a faculty member at the Centre for the Study of Human Rights, London School of Economics. Cochrane is a Sentientist. Sentientism is a naturalistic worldview that grants moral consideration to all sentient beings.

The Center for the Study of Bioethics (CSB) is a bioethics research institute based in Belgrade, Serbia. It was founded in 2012 by the Serbian American philosopher Vojin Rakić. CSB is a scientific institution which cooperates closely with the University of Belgrade, maintaining at the same time a strong international focus. In 2015 UNESCO named CSB director, Vojin Rakić, Head of the European Division of the UNESCO Chair in Bioethics, thus making CSB the seat of this Division. The Cambridge Working Group for Bioethics Education in Serbia was also constituted at the Center for the Study of Bioethics.

Françoise Elvina BaylisFISC is a Canadian bioethicist whose work is at the intersection of applied ethics, health policy, and practice. The focus of her research is on issues of women's health and assisted reproductive technologies, but her research and publication record also extend to such topics as research involving humans, gene editing, novel genetic technologies, public health, the role of bioethics consultants, and neuroethics. Baylis' interest in the impact of bioethics on health and public policy as well as her commitment to citizen engagement]and participatory democracy sees her engage with print, radio, television, and other online publications.

Human germline engineering is the process by which the genome of an individual is edited in such a way that the change is heritable. This is achieved by altering the genes of the germ cells, which then mature into genetically modified eggs and sperm. For safety, ethical, and social reasons, there is broad agreement among the scientific community and the public that germline editing for reproduction is a red line that should not be crossed at this point in time. There are differing public sentiments, however, on whether it may be performed in the future depending on whether the intent would be therapeutic or non-therapeutic.

S. Matthew Liao is an American philosopher specializing in bioethics and normative ethics. He is internationally known for his work on topics including children’s rights and human rights, novel reproductive technologies, neuroethics, and the ethics of artificial intelligence. Liao currently holds the Arthur Zitrin Chair of Bioethics, and is the Director of the Center for Bioethics and Affiliated Professor in the Department of Philosophy at New York University. He has previously held appointments at Oxford, Johns Hopkins, Georgetown, and Princeton.

Deakin University Lecturer in Health Ethics and Professionalism Tamara Kayali Browne and University of Oxford Senior Research Fellow Steve Clarke understand bioconservatism as "a term that is often used to describe those who wish to conserve humanity as it is, and so oppose human enhancement."

The ethics of uncertain sentience refers to questions surrounding the treatment of and moral obligations towards individuals whose sentience—the capacity to subjectively sense and feel—and resulting ability to experience pain is uncertain; the topic has been particularly discussed within the field of animal ethics, with the precautionary principle frequently invoked in response.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Douglas, T (2008). "Moral enhancement". Journal of Applied Philosophy. 25 (3): 228–245. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5930.2008.00412.x. PMC 2614680 . PMID 19132138.

- 1 2 Persson, I.; Savulescu, J. (2016). "Enharrisment: A reply to John Harris about moral enhancement". Neuroethics. 9 (3): 275–277. doi:10.1007/s12152-016-9274-7. S2CID 148280154.

- ↑ Rakić, V.; Wiseman, H. (2018). "Different games of moral bioenhancement". Bioethics. 32 (2): 103–110. doi:10.1111/bioe.12415. PMID 29205423. S2CID 3765284.

- 1 2 3 4 Specker, J.; Focquaert, F.; Raus, K.; Sterckx, S.; Schermer, M. (2014). "The ethical desirability of moral bioenhancement: a review of reasons". BMC Medical Ethics. 15: 67. doi: 10.1186/1472-6939-15-67 . PMC 4274726 . PMID 25227512.

- 1 2 Paulo, N. & Bublitz, J.C. (2017). How (not) to argue for moral enhancement: reflections on a decade of debate. Topoi, 1-15. doi:10.1007/s11245-017-9492-6

- ↑ Persson, I.; Savulescu, J. (2008). "The perils of cognitive enhancement and the urgent imperative to enhance the moral character of humanity". Journal of Applied Philosophy. 25 (3): 162–177. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5930.2008.00410.x.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Persson, I., & Savulescu, J. (2012a). Unfit for the future: The need for moral enhancement. New York: Oxford University Press.

- 1 2 3 4 Savulescu, J.; Persson, I. (2012b). "Moral enhancement". Philosophy Now. 91: 6–8.

- ↑ Savulescu, J.; Persson, I. (2012c). "Moral enhancement, freedom and the God machine". The Monist. 95 (3): 399–421. doi:10.5840/monist201295321. PMC 3431130 . PMID 22942461.

- ↑ Persson, I.; Savulescu, J. (2014). "Reply to commentators on Unfit for the Future". Journal of Medical Ethics. 41 (4): 348–352. doi:10.1136/medethics-2013-101796. PMID 24413582. S2CID 2629575.

- 1 2 Raus, K.; Focquaert, F.; Schermer, M.; Specker, J.; Sterckx, S. (2014). "On defining moral enhancement: a clarificatory taxonomy". Neuroethics. 7 (3): 263–273. doi:10.1007/s12152-014-9205-4. hdl: 1854/LU-4323993 . S2CID 53124507.

- 1 2 3 4 Rakić, V (2014a). "Voluntary moral enhancement and the survival-at-any-cost bias". Journal of Medical Ethics. 40 (4): 246–250. doi:10.1136/medethics-2012-100700. PMID 23412695. S2CID 33619158.

- ↑ Rakić, V (2014b). "Voluntary moral bioenhancement is a solution to Sparrow's concerns". The American Journal of Bioethics. 14 (4): 37–38. doi:10.1080/15265161.2014.889249. PMID 24730490. S2CID 42768609.

- ↑ Rakić, Vojin (2019). "Genome Editing for Involuntary Moral Enhancement". Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics. 28 (1): 46–54. doi:10.1017/S0963180118000373. PMID 30570463. S2CID 58548473.

- ↑ Crutchfield, Parker (January 2019). "Compulsory moral bioenhancement should be covert". Bioethics. 33 (1): 112–121. doi: 10.1111/bioe.12496 . ISSN 1467-8519. PMID 30157295. S2CID 52122178.

- ↑ Schaefer, G. Owen (2015). "Direct vs. Indirect Moral Enhancement". Kennedy Institute of Ethics Journal. 25 (3): 261–289. doi:10.1353/ken.2015.0016. ISSN 1086-3249. PMID 26412738. S2CID 35532005.

- ↑ Willows, Adam M. (2017-04-03). "Supplementing Virtue: The Case for a Limited Theological Transhumanism" (PDF). Theology and Science. 15 (2): 177–187. doi:10.1080/14746700.2017.1299375. ISSN 1474-6700. S2CID 152151008.

- 1 2 Walker, M. (2009). "Enhancing genetic virtue: A project for twenty-first century humanity?". Politics and the Life Sciences. 28 (2): 27–47. doi:10.2990/28_2_27. PMID 20205521. S2CID 41544138.

- ↑ Milton, John (1674). Paradise Lost; A Poem in Twelve Books (II ed.). London: S. Simmons. Retrieved 8 January 2017– via Internet Archive.

- ↑ "Paradise Lost: Introduction". Dartmouth College. Retrieved 26 March 2010.

- ↑ Harris, John (2011). "Moral Enhancement and Freedom". Bioethics. 25 (2): 102–11. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8519.2010.01854.x. PMC 3660783 . PMID 21133978.

- 1 2 Douglas, Thomas (2013). "Moral Enhancement via Direct Emotion Modulation: A Reply to John Harris". Bioethics. 27 (3): 160–168. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8519.2011.01919.x. PMC 3378474 . PMID 22092503.

- 1 2 3 4 DeGrazia, David (2014). "Moral Enhancement, Freedom, and What We (Should) Value in Moral Behaviour". Journal of Medical Ethics. 40 (6): 361–368. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2012-101157 . PMID 23355049.

- ↑ Bourget, David; Chalmers, David (2014). "What Do Philosophers Believe?". Philosophical Studies (3 ed.). 170 (3): 465–500. doi:10.1007/s11098-013-0259-7. S2CID 170254281.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Murray, T (2012). "The incoherence of moral bioenhancement". Philosophy Now. 93: 19–21.

- ↑ Beck, B (2015). "Conceptual and practical problems of moral enhancement". Bioethics. 29 (4): 233–240. doi:10.1111/bioe.12090. PMID 24654942. S2CID 25637842.

- 1 2 Fabiano, Joao (October 13, 2017). "A Fundamental Problem with Moral Enhancement". University of Oxford Practical Ethics.

- ↑ Dubljević, V.; Racine, E. (2017). "Moral enhancement meets normative and empirical reality: Assessing the practical feasibility of moral enhancement neurotechnologies". Bioethics. 31 (5): 338–348. doi:10.1111/bioe.12355. PMID 28503833. S2CID 5219014.

- 1 2 Bostrom, N (2007). "Smart Policy: Cognitive Enhancement in the Public Interest". Forthcoming in (Title-to-be-determined) Rathenau Institute in Collaboration with the UK Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology: 2008: 4.

- ↑ Melo-Martin, I.; Salles, A. (2015). "Moral bioenhancement: much ado about nothing?". Bioethics. 29 (4): 223–232. doi:10.1111/bioe.12100. PMID 24909343. S2CID 2661124.

- ↑ Ram-Tiktin, E (2014). "The possible effects of moral bioenhancement on political privileges and fair equality of opportunity". The American Journal of Bioethics. 14 (4): 43–44. doi:10.1080/15265161.2014.889246. PMID 24730492. S2CID 29808792.

- ↑ Archer, A (2016). "Moral enhancement and those left behind". Bioethics. 30 (7): 500–510. doi:10.1111/bioe.12251. PMID 26833687. S2CID 207066718.