Background

Burgundian and Habsburg territorial expansion

In a series of marriages and conquests, a succession of dukes of Burgundy expanded their original territory by adding to it a series of fiefdoms, including the Seventeen Provinces. [3] Under the Burgundians (and their Habsburg successors), their holdings in the Low Countries were formally referred to as "De landen van herwaarts over" and in French "Les pays de par deçà". Translated, the phrases mean "those lands around here" for the Dutch and "those lands around there" for the French.[ citation needed ]

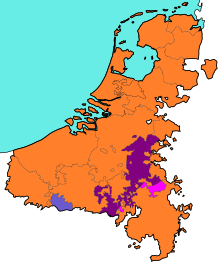

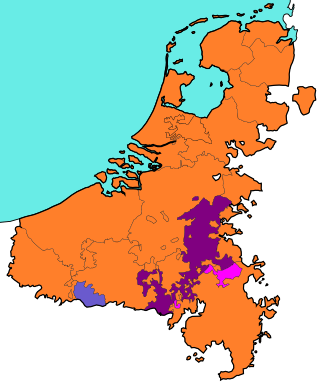

The death of Burgundian duke Charles the Bold during the Battle of Nancy (5 January 1477) created an instant crisis for the Burgundian State. He had no male heirs, and the French and Swiss immediately invaded his lands, starting the War of the Burgundian Succession (1477–1482/93). The Duchy of Burgundy itself was lost to France in 1477, but the Burgundian Netherlands were still intact when Charles of Habsburg, heir to the Netherlands via his grandmother Mary, was born in Ghent in 1500. Charles was raised in the Netherlands and spoke fluent Dutch, French, and Spanish, along with some German. [4] In 1506, he became lord of the Netherlands. In 1516, he inherited the kingdoms of Spain, which had become a worldwide empire with the Spanish colonization of the Americas, and in 1519, he inherited the Archduchy of Austria. Finally, he was elected Holy Roman Emperor in 1530. [5] Although Frisia and Guelders offered prolonged resistance under Grutte Pier and Charles of Egmond respectively during the Guelders Wars (1502–1543), virtually all of the Netherlands had been incorporated into the Habsburg domains by the early 1540s.[ citation needed ]

Habsburg centralisation

Part of the shifting balance of power in the late Middle Ages meant that besides the local nobility, many of the Dutch administrators by now were not traditional aristocrats but instead stemmed from non-noble families that had risen in status over previous centuries. By the 15th century, Brussels had thus become the de facto capital of the Seventeen Provinces. Dating back to the Middle Ages, the districts of the Netherlands, represented by its nobility and the wealthy city-dwelling merchants, still had a large measure of autonomy in appointing its administrators. The first meeting of the States General of the Netherlands occurred in 1464 during the reign of Philip the Good. On 11 February 1477, the States-General managed to force Mary of Burgundy to grant them the Great Privilege, a collection of rights and privileges that the Burgundian dukes and duchesses were supposed to respect. Charles V and Philip II set out to improve the management of the empire by increasing the authority of the central government in matters like law and taxes, [6] a policy which caused suspicion among the nobility and the merchant class. An example of this is the takeover of power in the city of Utrecht in 1528, when Charles V supplanted the council of guild masters governing the city by his own stadtholder, who took over worldly powers in the whole province of Utrecht from the archbishop of Utrecht. Charles ordered the construction of the heavily fortified castle of Vredenburg for defence against the Duchy of Gelre and to control the citizens of Utrecht. [7]

Under the governorship of Mary of Hungary (1531–1555), traditional power had largely been removed from both the stadtholders of the provinces and the high noblemen, who had been replaced by professional jurists in the Council of State. [8]

Taxation

Flanders had long been a very wealthy region, coveted by French kings. The other regions of the Netherlands had also grown wealthy and entrepreneurial. [9] Charles V's empire had become a worldwide empire with large American and European territories. The latter were, however, distributed throughout Europe. Control and defense of these were hampered by the disparity of the territories and the huge length of the empire's borders. This large realm was almost continuously at war with its neighbors in its European heartlands, most notably against France in the Italian Wars and against the Ottoman Empire in the Mediterranean Sea. Other wars were fought against Protestant princes in Germany. The Dutch paid heavy taxes to fund these wars, [10] but perceived them as unnecessary and sometimes downright harmful because they were directed against their most important trading partners.[ citation needed ]

Protestant Reformation

During the 16th century, Protestantism rapidly gained ground in northern Europe. The Protestant Reformation led to the spread of Anabaptism of the Dutch reformer Menno Simons and the teachings of foreign Protestant leaders like Martin Luther and John Calvin. Dutch Protestants, after initial repression, were tolerated by local authorities. [11] By the 1560s, the Protestant community had become a significant influence in the Netherlands, although still a minority. [12] In a society dependent on trade, freedom and tolerance were considered essential. Nevertheless, Charles V, and from 1555 his successor Philip II, felt it was their duty to defeat Protestantism, [5] which was considered a heresy by the Catholic Church and a threat to the stability of the whole hierarchical political system. On the other hand, the intensely moralistic Dutch Protestants insisted their theology, sincere piety, and humble lifestyle was morally superior to the luxurious habits and superficial religiosity of the ecclesiastical nobility. [13] The harsh measures of suppression led to increasing grievances in the Netherlands, where the local governments had embarked on a course of peaceful coexistence. In the second half of the century, the situation escalated. Philip sent troops to crush the rebellion and make the Netherlands Catholic once again. Although failing in his attempts to introduce the Spanish Inquisition directly, the Inquisition of the Netherlands (existed until 1566) was nevertheless sufficiently severe and arbitrary to provoke fervent dislike. [14]