The bladder is a hollow organ in humans and other vertebrates that stores urine from the kidneys before disposal by urination. In placental mammals, urine enters the bladder via the ureters and exits via the urethra. In humans, the bladder is a distensible organ that sits on the pelvic floor. The typical adult human bladder will hold between 300 and 500 ml before the urge to empty occurs, but can hold considerably more.

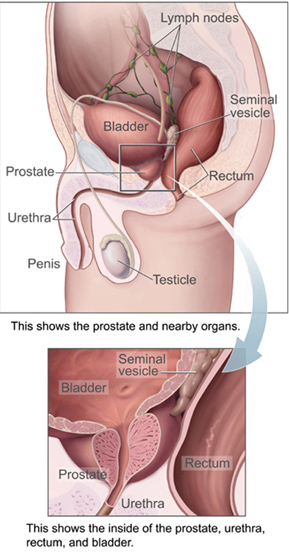

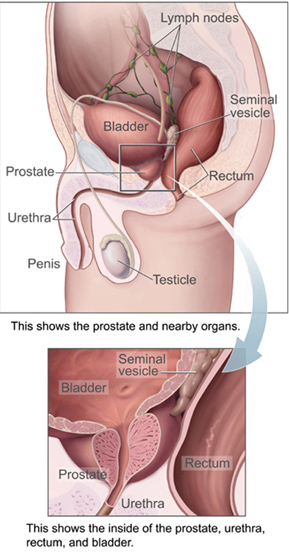

The prostate is both an accessory gland of the male reproductive system and a muscle-driven mechanical switch between urination and ejaculation. It is found in all male mammals. It differs between species anatomically, chemically, and physiologically. Anatomically, the prostate is found below the bladder, with the urethra passing through it. It is described in gross anatomy as consisting of lobes and in microanatomy by zone. It is surrounded by an elastic, fibromuscular capsule and contains glandular tissue, as well as connective tissue.

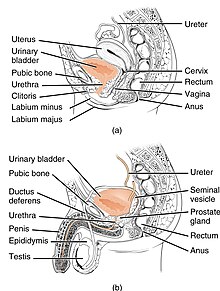

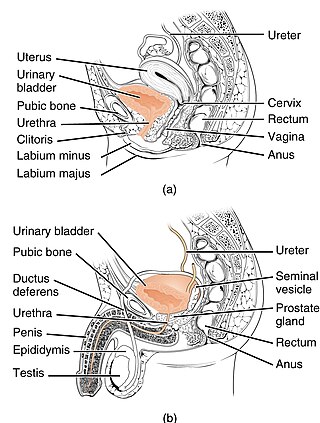

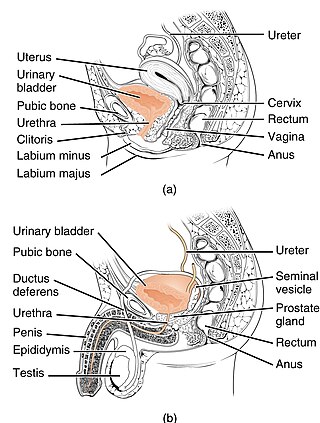

The human urinary system, also known as the urinary tract or renal system, consists of the kidneys, ureters, bladder, and the urethra. The purpose of the urinary system is to eliminate waste from the body, regulate blood volume and blood pressure, control levels of electrolytes and metabolites, and regulate blood pH. The urinary tract is the body's drainage system for the eventual removal of urine. The kidneys have an extensive blood supply via the renal arteries which leave the kidneys via the renal vein. Each kidney consists of functional units called nephrons. Following filtration of blood and further processing, wastes exit the kidney via the ureters, tubes made of smooth muscle fibres that propel urine towards the urinary bladder, where it is stored and subsequently expelled from the body by urination. The female and male urinary system are very similar, differing only in the length of the urethra.

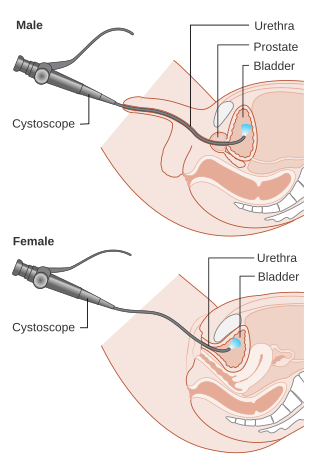

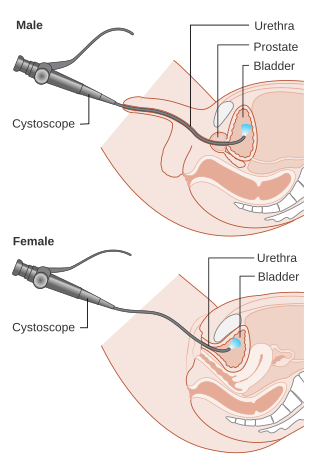

Cystoscopy is endoscopy of the urinary bladder via the urethra. It is carried out with a cystoscope.

Urination is the release of urine from the bladder to the outside of the body. Urine is released from the urethra through the penis or vulva in placental mammals and through the cloaca in other vertebrates. It is the urinary system's form of excretion. It is also known medically as micturition, voiding, uresis, or, rarely, emiction, and known colloquially by various names including peeing, weeing, pissing, and euphemistically going number one. The process of urination is under voluntary control in healthy humans and other animals, but may occur as a reflex in infants, some elderly individuals, and those with neurological injury. It is normal for adult humans to urinate up to seven times during the day.

Urinary incontinence (UI), also known as involuntary urination, is any uncontrolled leakage of urine. It is a common and distressing problem, which may have a large impact on quality of life. It has been identified as an important issue in geriatric health care. The term enuresis is often used to refer to urinary incontinence primarily in children, such as nocturnal enuresis. UI is an example of a stigmatized medical condition, which creates barriers to successful management and makes the problem worse. People may be too embarrassed to seek medical help, and attempt to self-manage the symptom in secrecy from others.

The ureters are tubes composed of smooth muscle that transport urine from the kidneys to the urinary bladder. In an adult human, the ureters typically measure 20 to 30 centimeters in length and about 3 to 4 millimeters in diameter. They are lined with urothelial cells, a form of transitional epithelium, and feature an extra layer of smooth muscle in the lower third to aid in peristalsis. The ureters can be affected by a number of diseases, including urinary tract infections and kidney stone. Stenosis is when a ureter is narrowed, due to for example chronic inflammation. Congenital abnormalities that affect the ureters can include the development of two ureters on the same side or abnormally placed ureters. Additionally, reflux of urine from the bladder back up the ureters is a condition commonly seen in children.

Hematuria or haematuria is defined as the presence of blood or red blood cells in the urine. "Gross hematuria" occurs when urine appears red, brown, or tea-colored due to the presence of blood. Hematuria may also be subtle and only detectable with a microscope or laboratory test. Blood that enters and mixes with the urine can come from any location within the urinary system, including the kidney, ureter, urinary bladder, urethra, and in men, the prostate. Common causes of hematuria include urinary tract infection (UTI), kidney stones, viral illness, trauma, bladder cancer, and exercise. These causes are grouped into glomerular and non-glomerular causes, depending on the involvement of the glomerulus of the kidney. But not all red urine is hematuria. Other substances such as certain medications and foods can cause urine to appear red. Menstruation in women may also cause the appearance of hematuria and may result in a positive urine dipstick test for hematuria. A urine dipstick test may also give an incorrect positive result for hematuria if there are other substances in the urine such as myoglobin, a protein excreted into urine during rhabdomyolysis. A positive urine dipstick test should be confirmed with microscopy, where hematuria is defined by three or more red blood cells per high power field. When hematuria is detected, a thorough history and physical examination with appropriate further evaluation can help determine the underlying cause.

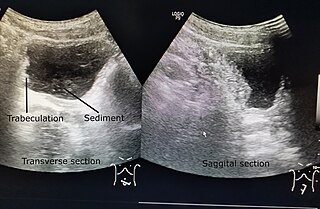

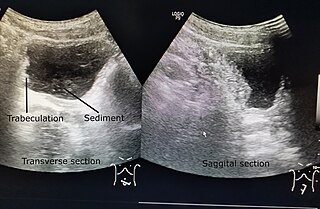

Urinary retention is an inability to completely empty the bladder. Onset can be sudden or gradual. When of sudden onset, symptoms include an inability to urinate and lower abdominal pain. When of gradual onset, symptoms may include loss of bladder control, mild lower abdominal pain, and a weak urine stream. Those with long-term problems are at risk of urinary tract infections.

The external sphincter muscle of male urethra, also sphincter urethrae membranaceae, sphincter urethrae externus, surrounds the whole length of the membranous urethra, and is enclosed in the fascia of the urogenital diaphragm.

In urology, voiding cystourethrography (VCUG) is a frequently performed technique for visualizing a person's urethra and urinary bladder while the person urinates (voids). It is used in the diagnosis of vesicoureteral reflux, among other disorders. The technique consists of catheterizing the person in order to fill the bladder with a radiocontrast agent, typically diatrizoic acid. Under fluoroscopy the radiologist watches the contrast enter the bladder and looks at the anatomy of the patient. If the contrast moves into the ureters and back into the kidneys, the radiologist makes the diagnosis of vesicoureteral reflux, and gives the degree of severity a score. The exam ends when the person voids while the radiologist is watching under fluoroscopy. Consumption of fluid promotes excretion of contrast media after the procedure. It is important to watch the contrast during voiding, because this is when the bladder has the most pressure, and it is most likely this is when reflux will occur. Despite this detailed description of the procedure, at least as of 2016 the technique had not been standardized across practices.

Neurogenic bladder dysfunction, often called by the shortened term neurogenic bladder, refers to urinary bladder problems due to disease or injury of the central nervous system or peripheral nerves involved in the control of urination. There are multiple types of neurogenic bladder depending on the underlying cause and the symptoms. Symptoms include overactive bladder, urinary urgency, frequency, incontinence or difficulty passing urine. A range of diseases or conditions can cause neurogenic bladder including spinal cord injury, multiple sclerosis, stroke, brain injury, spina bifida, peripheral nerve damage, Parkinson's disease, multiple system atrophy or other neurodegenerative diseases. Neurogenic bladder can be diagnosed through a history and physical as well as imaging and more specialized testing. In addition to symptomatic treatment, treatment depends on the nature of the underlying disease and can be managed with behavioral changes, medications, surgeries, or other procedures. The symptoms of neurogenic bladder, especially incontinence, can severely degrade a person's quality of life.

Urethral cancer is a rare cancer originating from the urethra. The disease has been classified by the TNM staging system and the World Health Organization.

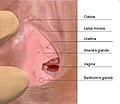

The urinary meatus, also known as the external urethral orifice, is the opening where urine exits the male and female urethra. It is where semen also exits the male urethra. The meatus has varying degrees of sensitivity to touch.

The urethral sphincters are two muscles used to control the exit of urine in the urinary bladder through the urethra. The two muscles are either the male or female external urethral sphincter and the internal urethral sphincter. When either of these muscles contracts, the urethra is sealed shut.

The internal urethral sphincter is a urethral sphincter muscle which constricts the internal urethral orifice. It is located at the junction of the urethra with the urinary bladder and is continuous with the detrusor muscle, but anatomically and functionally fully independent from it. It is composed of smooth muscle, so it is under the control of the autonomic nervous system, specifically the sympathetic nervous system.

A retrograde urethrography is a routine radiologic procedure used to image the integrity of the urethra. Hence a retrograde urethrogram is essential for diagnosis of urethral injury, or urethral stricture.

Urologic diseases or conditions include urinary tract infections, kidney stones, bladder control problems, and prostate problems, among others. Some urologic conditions do not affect a person for that long and some are lifetime conditions. Kidney diseases are normally investigated and treated by nephrologists, while the specialty of urology deals with problems in the other organs. Gynecologists may deal with problems of incontinence in women.

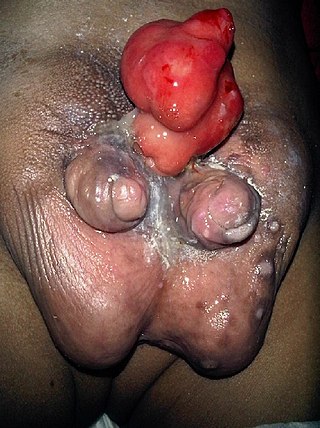

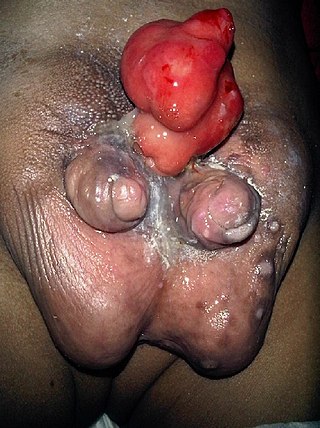

Diphallia, penile duplication (PD), diphallic terata, or diphallasparatus is an extremely rare developmental abnormality in which a male is born with two penises. The first reported case was by Johannes Jacob Wecker in 1609. Its occurrence is 1 in 5.5 million boys in the United States.

Ureteral cancer is cancer of the ureters, muscular tubes that propel urine from the kidneys to the urinary bladder. It is also known as ureter cancer, renal pelvic cancer, and rarely ureteric cancer or uretal cancer. Cancer in this location is rare. Ureteral cancer becomes more likely in older adults, usually ages 70–80, who have previously been diagnosed with bladder cancer.