The 14th Street bridges refers to the three bridges near each other that cross the Potomac River, connecting Arlington, Virginia and Washington, D.C.. Sometimes the two nearby rail bridges are included as part of the 14th Street bridge complex. A major gateway for automotive, bicycle and rail traffic, the bridge complex is named for 14th Street, which feeds automotive traffic into it on the D.C. end.

The Arlington Memorial Bridge is a Neoclassical masonry, steel, and stone arch bridge with a central bascule that crosses the Potomac River at Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States. First proposed in 1886, the bridge went unbuilt for decades thanks to political quarrels over whether the bridge should be a memorial, and to whom or what. Traffic problems associated with the dedication of the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in November 1921 and the desire to build a bridge in time for the bicentennial of the birth of George Washington led to its construction in 1932.

The Francis Scott Key Bridge, more commonly known as the Key Bridge, is a six-lane reinforced concrete arch bridge conveying U.S. Route 29 (US 29) traffic across the Potomac River between the Rosslyn neighborhood of Arlington County, Virginia, and the Georgetown neighborhood of Washington, D.C. Completed in 1923, it is Washington's oldest surviving road bridge across the Potomac River.

Constitution Avenue is a major east–west street in the northwest and northeast quadrants of the city of Washington, D.C., in the United States. It was originally known as B Street, and its western section was greatly lengthened and widened between 1925 and 1933. It received its current name on February 26, 1931, though it was almost named Jefferson Avenue in honor of Thomas Jefferson. Constitution Avenue's western half defines the northern border of the National Mall and extends from the United States Capitol to the Theodore Roosevelt Bridge. Its eastern half runs through the neighborhoods of Capitol Hill and Kingman Park before it terminates at Robert F. Kennedy Memorial Stadium. Many federal departmental headquarters, memorials, and museums line Constitution Avenue's western segment.

The John Philip Sousa Bridge, also known as the Sousa Bridge and the Pennsylvania Avenue Bridge, is a continuous steel plate girder bridge that carries Pennsylvania Avenue SE across the Anacostia River in Washington, D.C., in the United States. The bridge is named for famous United States Marine Band conductor and composer John Philip Sousa, who grew up near the bridge's northwestern terminus.

The Dumbarton Bridge, also known as the Q Street Bridge and the Buffalo Bridge, is a historic masonry arch bridge in Washington, D.C.

East Potomac Park is a park located on a man-made island in the Potomac River in Washington, D.C., United States. The island is between the Washington Channel and the Potomac River, and on it the park lies southeast of the Jefferson Memorial and the 14th Street Bridge. Amenities in East Potomac Park include the East Potomac Park Golf Course, a miniature golf course, a public swimming pool, tennis courts, and several athletic fields. The park is a popular spot for fishing, and cyclists, walkers, inline skaters, and runners heavily use the park's roads and paths. A portion of Ohio Drive SW runs along the perimeter of the park.

The 11th Street Bridges are a complex of three bridges across the Anacostia River in Washington, D.C., United States. The bridges convey Interstate 695 across the Anacostia to its southern terminus at Interstate 295 and DC 295. The bridges also connect the neighborhood of Anacostia with the rest of the city of Washington.

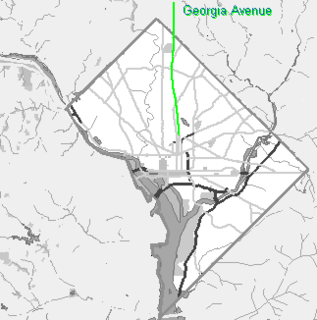

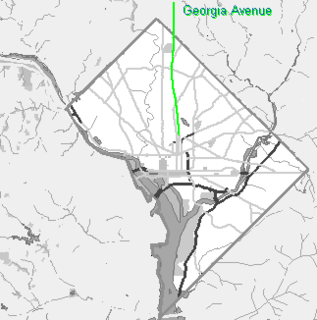

Georgia Avenue is a major north-south artery in Northwest Washington, D.C. and Montgomery County, Maryland. Within the District of Columbia and a short distance in Silver Spring, Maryland, Georgia Avenue is also U.S. Route 29. Both Howard University and Walter Reed Army Medical Center are located on Georgia Avenue.

New Hampshire Avenue is a diagonal street in Washington, D.C., beginning at the Kennedy Center and extending northeast for about 5 miles (8 km) and then continuing into Maryland where it is designated Maryland Route 650. New Hampshire Avenue, however, is not contiguous. It stops at 15th and W Streets NW and resumes again on the other side of Columbia Heights at Park Road NW, a few blocks from Georgia Avenue. New Hampshire Avenue passes through several Washington neighborhoods including Foggy Bottom, Dupont Circle, Petworth and Lamond-Riggs.

Prospect Hill Cemetery, also known as the German Cemetery, is a historic German-American cemetery founded in 1858 and located at 2201 North Capitol Street in Washington, D.C. From 1886 to 1895, the Prospect Hill Cemetery board of directors battled a rival organization which illegally attempted to take title to the grounds and sell a portion of them as building lots. From 1886 to 1898, the cemetery also engaged in a struggle against the District of Columbia and the United States Congress, which wanted construct a main road through the center of the cemetery. This led to the passage of an Act of Congress, the declaration of a federal law to be unconstitutional, the passage of a second Act of Congress, a second major court battle, and the declaration by the courts that the city's eminent domain procedures were unconstitutional. North Capitol Street was built, and the cemetery compensated fairly for its property.

The Ethel Kennedy Bridge is a beam bridge built in 2004 that carries Benning Road over the Anacostia River in Washington, D.C. It is an eight-lane bridge with pedestrian lanes on both sides. A separate Washington Metro bridge carrying the Blue, Orange and Silver lines crosses over the bridge near its western terminus, and parallels the bridge on the north. A third bridge in the area carries Benning Road over Kingman Lake.

The Amtrak Railroad Anacostia Bridge is a railway-only bridge which crosses the Anacostia River in Washington, D.C. It carries Amtrak's Northeast Corridor and MARC's Penn Line passenger rail traffic. It was the site of the famous "Crescent Limited wreck" in August 1933, caused when the bridge was damaged by the 1933 Chesapeake–Potomac hurricane.

Piney Branch is a tributary of Rock Creek in Washington, D.C. It is the largest tributary located entirely within the Washington city limits.

Boundary Channel is a channel off the Potomac River in Washington, D.C. The channel begins at the northwestern tip of Columbia Island extends southward between Columbia Island and the Virginia shoreline. It curves around the southern tip of Columbia Island before heading northeast to exit into the Potomac River. At the southwestern tip of Columbia Island, the Boundary Channel widens into the manmade Pentagon Lagoon.

The construction of Arlington Memorial Bridge was a seven-year construction project in Washington, D.C., in the United States to construct the Arlington Memorial Bridge across the Potomac River. The bridge was authorized by Congress in February 1925, and was completed in January 1932. As a memorial, its decorative features were extensive and intricate, and resolving the design issues over these details took many years. Tall columns and pylons topped by statuary, Greek Revival temple-like structures, and statue groups were proposed for the ends of the bridge. Carvings and inscriptions were planned for the sides of the bridge, and extensive statuary for the bridge piers.

Long Bridge is the common name used for a series of three bridges connecting Washington, D.C. to Arlington, Virginia over the Potomac River. The first was built in 1808 for foot, horse and stagecoach traffic. Bridges in the vicinity were repaired and replaced several times in the 19th century. The current bridge was built in 1904 and substantially modified in 1942 and has only been used for railroad traffic. It is owned by CSX Transportation and is used by CSX freight trains, Amtrak intercity trains, and Virginia Railway Express commuter trains. Norfolk Southern Railway has trackage rights on the bridge but does not exercise those rights. In 2019 Virginia announced that it would help fund and build a new rail bridge parallel to the existing one to double its capacity, following the plans that have been studied by the District Department of Transportation (DDOT) and Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) since 2011.

The New York Avenue Bridge is a bridge carrying U.S. Route 50 and New York Avenue NE over the Anacostia River in Washington, D.C., in the United States. It was completed in 1954 as part of the Baltimore–Washington Parkway project.

The Pennsylvania Avenue Bridge was a crossing of the Anacostia River in Washington, DC at the site of the present John Philip Sousa Bridge. It was constructed in 1890 and demolished around 1939.

Nathan Corwith Wyeth was an American architect. He is best known for designing the West Wing of the White House, creating the first Oval Office. He designed a large number of structures in Washington, D.C., including the Francis Scott Key Bridge over the Potomac River, the USS Maine Mast Memorial, the D.C. Armory, the Tidal Basin Inlet Bridge, many structures that comprise Judiciary Square, and numerous private homes—many of which now serve as embassies. He also co-designed the Cannon House Office Building, the Russell Senate Office Building, the Longworth House Office Building, and an addition to the Russell Senate Office Building.