Liberia is a country in West Africa founded by free people of color from the United States. The emigration of African Americans, both freeborn and recently emancipated, was funded and organized by the American Colonization Society (ACS). The mortality rate of these settlers was the highest among settlements reported with modern recordkeeping. Of the 4,571 emigrants who arrived in Liberia between 1820 and 1843, only 1,819 survived (39.8%).

The flag of Liberia, occasionally referred to as the Lone Star, bears a close resemblance to the flag of the United States, representing Liberia's founding by former black slaves from the United States and the Caribbean. They are both part of the stars and stripes flag family.

The American Colonization Society (ACS), initially the Society for the Colonization of Free People of Color of America, was an American organization founded in 1816 by Robert Finley to encourage and support the repatriation of freeborn people of color and emancipated slaves to the continent of Africa. It was modeled on an earlier British Committee for the Relief of the Black Poor's colonization in Africa, which had sought to resettle London's "black poor". Until the organization's dissolution in 1964, the society was headquartered in Room 516 of the Colorado Building in Washington, D.C.

Joseph Jenkins Roberts was an American merchant who emigrated to Liberia in 1829, where he became a politician. Elected as the first (1848–1856) and seventh (1872–1876) president of Liberia after independence, he was the first man of African descent to govern the country, serving previously as governor from 1841 to 1848. He later returned to office following the 1871 Liberian coup d'état. Born free in Norfolk, Virginia, Roberts emigrated as a young man with his mother, siblings, wife, and child to the young West African colony. He opened a trading firm in Monrovia and later engaged in politics.

Jehudi Ashmun was an American religious leader and social reformer from New England who helped lead efforts by the American Colonization Society to "repatriate" African Americans to a colony in West Africa. It founded the colony of Liberia in West Africa as a place to resettle free people of color from the United States.

Ralph Randolph Gurley was an American clergyman, an advocate of the separation of the races, and a major force for 50 years in the American Colonization Society. It offered passage to free black Americans to the ACS colony in west Africa. It bought land from chiefs of the indigenous Africans. Because of his influence in fundraising and education about the ACS, Gurley is considered one of the founders of Liberia, which he named.

Liberian nationality law is regulated by the Constitution of Liberia, as amended; the Aliens and Nationality Law, and its revisions; and various international agreements to which the country is a signatory. These laws determine who is, or is eligible to be, a national of Liberia. The legal means to acquire nationality, formal legal membership in a nation, differ from the domestic relationship of rights and obligations between a national and the nation, known as citizenship. Nationality describes the relationship of an individual to the state under international law, whereas citizenship is the domestic relationship of an individual within the nation. Liberian nationality is based on descent from a person who is "Negro", regardless of whether they were born on Liberian soil, jus soli, or abroad to Liberian parents, jus sanguinis. The Negro clause was inserted from the founding of the colony as a refuge for free people of color, and later former slaves, to prevent economically powerful communities from obtaining political power. It can be granted to persons with an affiliation to the country, or to a permanent resident who has lived in the country for a given period of time through naturalization.

Daniel Bashiel Warner served as the third president of Liberia from 1864 to 1868. Prior to this, he served as the third Secretary of State in the cabinet of Joseph Jenkins Roberts from 1854 to 1856 and the fifth vice president of Liberia under President Stephen Allen Benson from 1860 to 1864.

The Republic of Maryland was a country in West Africa that existed from 1834 to 1857, when it was merged into what is now Liberia. The area was first settled in 1834 by freed African-American slaves and freeborn African Americans primarily from the U.S. state of Maryland, under the auspices of the Maryland State Colonization Society.

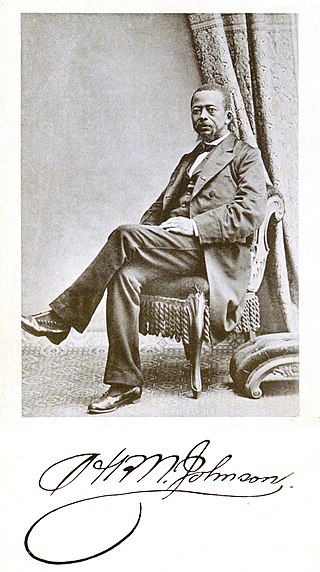

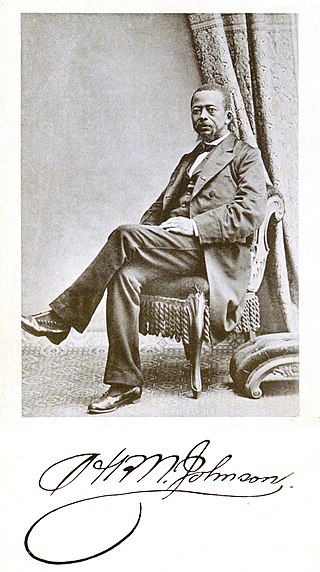

Hilary Richard Wright Johnson served as the 11th president of Liberia from 1884 to 1892. He was elected four times. He was the first Liberian president to be born in Africa. He had served as Secretary of State before his presidency, in the administration of Edward James Roye.

Mississippi-in-Africa was a colony on the Pepper Coast founded in the 1830s by the Mississippi Colonization Society of the United States and settled by American free people of color, many of them former slaves. In the late 1840s, some 300 former slaves from Prospect Hill Plantation and other Isaac Ross properties in Jefferson County, Mississippi, were the largest single group of emigrants to the new colony. Ross had freed the slaves in his will and provided for his plantation to be sold to pay for their transportation and initial costs.

The back-to-Africa movement was a political movement in the 19th and 20th centuries advocating for a return of the descendants of African American slaves to the African continent. The movement originated from a widespread belief among some European Americans in the 18th and 19th century United States that African Americans would want to return to the continent of Africa. In general, the political movement was an overwhelming failure; very few former slaves wanted to move to Africa. The small number of freed slaves who did settle in Africa—some under duress—initially faced brutal conditions, due to diseases to which they no longer had biological resistance. As the failure became known in the United States in the 1820s, it spawned and energized the radical abolitionist movement. In the 20th century, the Jamaican political activist and black nationalist Marcus Garvey, members of the Rastafari movement, and other African Americans supported the concept, but few actually left the United States.

Daniel Coker (1780–1846), born Isaac Wright, was an African American of mixed race from Baltimore, Maryland. Born a slave, after he gained his freedom, he became a Methodist minister in 1802. He wrote one of the few pamphlets published in the South that protested against slavery and supported abolition. In 1816, he helped found the African Methodist Episcopal Church, the first independent black denomination in the United States, at its first national convention in Philadelphia.

John Kizell was an American immigrant who became a leader in Sierra Leone as it was being developed as a new British colony in the early nineteenth century. Believed born on Sherbro Island, he was kidnapped and enslaved as a child and shipped to Charleston, South Carolina, where he was sold again. Years later, after the American Revolutionary War, during which he gained freedom with the British and was evacuated to Nova Scotia, he eventually returned to West Africa. In 1792, he was among 50 native-born Africans among the 1200 predominantly African-American Black Loyalists resettled in Freetown.

Cape Mesurado, also called Cape Montserrado, is a headland on the coast of Liberia near the capital Monrovia and the mouth of the Saint Paul River. It was named Cape Mesurado by Portuguese sailors in the 1560s. It is the promontory on which African-American settlers established the city now called Monrovia on 25 April 1822.

The Liberian Declaration of Independence is a document adopted by the Liberian Constitutional Convention on 26 July 1847, to announce that the Commonwealth of Liberia, a colony founded and controlled by the private American Colonization Society, was an independent state known as the Republic of Liberia.

Nathaniel Brander (1796–1870) was an Americo-Liberian politician and jurist who served as the first vice president of Liberia from 1848 to 1850 under President Joseph Jenkins Roberts.

Americo-Liberian people, are a Liberian ethnic group of African American, Afro-Caribbean, and liberated African origin. Americo-Liberians trace their ancestry to free-born and formerly enslaved African Americans who emigrated in the 19th century to become the founders of the state of Liberia. They identified themselves as Americo-Liberians.

The African-American diaspora refers to communities of people of African descent who previously lived in the United States. These people were mainly descended from formerly enslaved African persons in the United States or its preceding European colonies in North America that had been brought to America via the Atlantic slave trade and had suffered in slavery until the American Civil War. The African-American diaspora was primarily caused by the intense racism and views of being inferior to white people that African Americans have suffered through driving them to find new homes free from discrimination and racism. This would become common throughout the history of the African-American presence in the United States and continues to this day.

Millsburg is a township in Liberia. It is in Montserrado County.