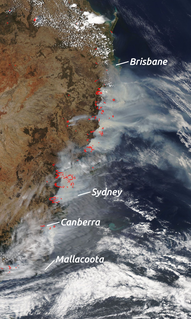

From 27 December 1993 to 16 January 1994, over 800 severe fires burned along the coastal areas of New South Wales, affecting the state's most populous regions. Blazes emerged from the Queensland border down the north and central coast, through the Sydney basin and down the south coast to Batemans Bay. The 800,000 hectare spread of fires were generally contained within less than 100 kilometres from the coast, and many burned through rugged and largely uninhabited country in national parks or nature reserves. [3]

Progression of the fires

The New South Wales fires began on the north coast on Boxing Day, and by January 2, the Clarence Valley region was facing its worst fires since 1968. The shires from Coffs Harbour to Tweed Heads and inland to Casino and Kyogle were declared a State of Emergency on January 7, as 68 fires raged. [4]

On 29 December, the Dept of Bushfire Services was monitoring more than a dozen fires around the state, and homes were threatened in Turramurra by a fire in the Lane Cove River reserve, and a scrub fire had briefly cut off the holiday village of Bundeena in the Royal National Park south of Sydney. [5]

On the south coast, fires ignited at Pretty Beach in the Murramarang National Park on 5 January, threatening Bendalong and Manyana, where hundredsd were evacuated. Other fires lit in the Morton National Park, and areas near Ulladulla and Sussex Inlet, where a house was lost on 7 January, while buildings burned at Dolphin Point, Ulladulla and the Princes Highway was cut near Burril Lake. The towns of Broulee and Mossy Point came under threat from a fire west of Mogo. Thousands of homes under threat in Batemans Bay and surrounds was considered safe by 10 January. The Waterfall fire forced evacuations in Helensburgh. [6]

Flames first struck the Sutherland Shire in Sydney's south on 5 January, when a fire, probably deliberately lit, burned out of the north east corner of the Royal National Park damaging houses at Bundeena and along Port Hacking. Back burning protected property, but nearly all 16,000 hectares of the national park was burned. Homes were lost at Menai, Illawong, Bangor and Alfreds Point. On Saturday the 8th, the fire swept into the suburbs of Como and [[Jannali, New South Wales|Jannali] where more than 100 building would be destroyed, including two schools a church and a kindergarten. [7] [8] The Como/Jannali fire burnt 476 hectares and destroyed 101 houses - more than half of the total homes lost in New South Wales during the January emergency period. [9] Also on 8 January, fires had reached to within 1.5km of Gosford city centre, and some 5000 people had been evacuated over that weekend with homes destroyed at Somersby and Peats Ridge. [10]

A fire was reported in the northern end of the Lane Cove National Park on 6 January. The blaze went on to consume 320 hectares of the Park and burn down 13 houses in 48 hours, racing down the river valley impacting West Pymble, West Killara, Linfield, Macquarie Park, and the Northern Suburbs Crematorium. [11]

By Friday, January 7, fires were raging to the north and south of Sydney and in its suburbs, leaving only local resources to be sent against suspicious fires that broke out in isolated country on the Bells Line of Road in the Blue Mountains, and spread quickly. By the following day, the Mount Wilson fire was raging out of control out of the Grose Valley, with 30 metre high flames, it consumed homes at Winmalee and Hawkesbury Heights. Roads through the Mountains were cut. On Sunday the "Battle of Bilpin" wave after wave of helicopters dumped water and saving further property loss, before conditions eased on Monday allowing massive back burning operations. [12]

The Age newspaper reported on 7 January that one quarter of NSW was under threat in the worst fires seen in the state for nearly 50 years, as hundreds of firefighters from interstate joined 4000 NSW firefighters battling blazes from Batemans Bay to Grafton. Fires in the Lane Cove River area at Marsfield, Turramurra, West Pymble and Macquarie Park were threatening hundreds of homes, and the fire in the Royal National Park south of Sydney raged toward Bundeena, where rescue boats evacuated 3100 people caught in the path of the fire. With the Prime Minister Paul Keating on leave, Deputy Prime Minister Brian Howe, ordered 100 soldiers to join firefighting efforts, and placed a further 100 on standby. [13]

A suspicious fire ignited at Cottage Point in Kuringai Chase National Park on 7 January and spread to burn down 30 houses and 10,000 hectares of the Park, with 3000 elsewhere. Major backburning protected the surrounding suburbs but smothered Sydney in smoke. [14]

By 9 January, more than 16,000 people were on standby for evacuation from the Lower Blue Mountains. Thousands of people were sleeping on the football field at the Central Coast Leagues Club, after the evacuation of Kariong, Woy Woy, Umina, Ettalong and Brisbane Waters. Much of Gosford, Kariong and Somersby had been evacuated, along with Terry Hill. Homes at Menai, Sutherland, Chatswood, Lindfield, Turramurra, Macquarie Park and Sydney's northern beaches had been lost. 60 fires were burning on the north coast, as firefighters battled infernos over 30 hectares from Coffs Harbour to the Queensland border. Fires were approaching towns in the Blue Mountains including Blackheath and in the Shoalhaven, including Ulladulla. [15]

By 15 January, about 450 square km had been burned in the Gosford area and fires in the Gospers Mountain/Wollemi National Park and west of the Kulnura and Mangrove Mountain were still causing ongoing concern for Gosford. Arsonists had lit blazes in the area, including a Mangrove Mountain fire threatening the city. [16]

Thirteen houses were destroyed in suburbs around Lane Cove National Park and 42 were destroyed around Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park, Garigal National Park and the Royal National Park, 9 houses including a Youth hostel were destroyed in Hawkesbury Heights in the Blue Mountains.