Killeen is a city in Bell County, Texas, United States. According to the 2020 census, its population was 153,095, making it the 19th-most populous city in Texas and the largest of the three principal cities of Bell County. It is the principal city of the Killeen–Temple–Fort Hood Metropolitan Statistical Area. Killeen is 55 miles (89 km) north of Austin, 125 miles (201 km) southwest of Dallas, and 125 miles (201 km) northeast of San Antonio.

Fort Hood is a United States Army post located near Killeen, Texas. Named after Confederate General John Bell Hood, it is located halfway between Austin and Waco, about 60 mi (97 km) from each, within the U.S. state of Texas. The post is the headquarters of III Armored Corps and First Army Division West and is home to the 1st Cavalry Division and 3rd Cavalry Regiment, among others. It is one of the U.S. Army installations named for Confederate soldiers to be renamed by the Commission on the Naming of Items of the Department of Defense that Commemorate the Confederate States of America or Any Person Who Served Voluntarily with the Confederate States of America. On 24 May 2022 the commission recommended the fort be renamed to Fort Cavazos, named after Gen. Richard E. Cavazos, a native Texan and the US Army’s first Hispanic four-star general. The recommendation report was finalized and submitted to Congress on 1 October 2022, giving the US Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin the authority to rename the post to Fort Cavazos. On 5 January 2023 William A. LaPlante, US under-secretary of defense for acquisition and sustainment directed the full implementation of the recommendations of the Naming Commission, DoD-wide.

Fragging is the deliberate or attempted killing by a soldier, usually a superior, by a fellow soldier. U.S. military personnel coined the word during the Vietnam War, when such killings were most often committed or attempted with a fragmentation grenade, to make it appear that the killing was accidental or during combat with the enemy. The term fragging now encompasses any deliberate killing of military colleagues.

Camp Bucca was a forward operating base that housed a theater internment facility maintained by the United States military in the vicinity of Umm Qasr, Iraq. After being taken over by the U.S. military in April 2003, it was renamed after Ronald Bucca, a NYC fire marshal who died in the 11 September 2001 attacks. The site where Camp Bucca was built had earlier housed the tallest structure in Iraq, a 492-meter-high TV mast.

The Luby's shooting was a mass shooting that took place on October 16, 1991, at a Luby's Cafeteria in Killeen, Texas. The perpetrator, George Hennard, drove his pickup truck through the front window of the restaurant. He shot and killed 23 people, and wounded 27 others. He had a brief shootout with police, was seriously wounded but refused their orders to surrender. He then fatally shot himself.

Gary Burnell Beikirch was a United States Army soldier who received the United States military's highest decoration, the Medal of Honor, for his actions during the Vietnam War. A combat medic, Beikirch was awarded the medal for exposing himself to intense fire in order to rescue and treat the wounded, and for continuing to provide medical care despite his own serious wounds, during a battle at Dak Seang Camp.

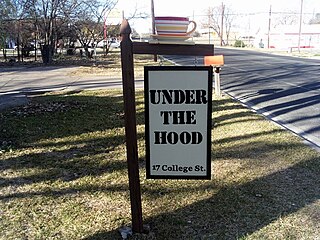

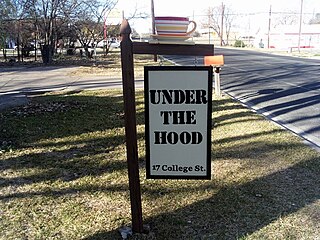

Under the Hood Café was a coffee house located at 17 South College Street in Killeen, Texas. It provided services for soldiers located at Fort Hood, one of the largest American military installation in the world. Under the Hood Café was first managed by Cynthia Thomas,

On November 5, 2009, a mass shooting took place at Fort Hood, near Killeen, Texas. Nidal Hasan, a U.S. Army major and psychiatrist, fatally shot 13 people and injured more than 30 others. It was the deadliest mass shooting on an American military base.

Nidal Malik Hasan is an American former Army major, physician and mass murderer convicted of killing 13 people and injuring more than 30 others in the Fort Hood mass shooting on November 5, 2009. Hasan was an Army Medical Corps psychiatrist. He admitted to the shootings at his court-martial in August 2013. A jury panel of 13 officers convicted him of 13 counts of premeditated murder, 32 counts of attempted murder, and unanimously recommended he be dismissed from the service and sentenced to death. Hasan is incarcerated at the United States Disciplinary Barracks at Fort Leavenworth in Kansas awaiting execution.

United States v. Hasan K. Akbar was the court-martial of a United States Army soldier for a premeditated attack in the early morning hours of March 23, 2003, at Camp Pennsylvania, Kuwait, during the start of the United States invasion of Iraq.

Leroy Arthur Petry is a retired United States Army soldier. He received the U.S. military's highest decoration, the Medal of Honor, for his actions in Afghanistan in 2008 during Operation Enduring Freedom.

Naser Jason Abdo is an American former US Army Private First Class who was arrested July 28, 2011, near Fort Hood, Texas, and was held without bond for possession of an unregistered firearm and allegedly planning to attack a restaurant frequented by soldiers from the base. He was convicted in federal court on May 24, 2012, of attempted use of a weapon of mass destruction, attempted murder of federal employees, and weapons charges. He was sentenced on August 10, 2012, to two consecutive life terms, plus 60 years.

On September 6, 2011, a gunman, identified as 32-year-old Eduardo Sencion, opened fire in a branch of the IHOP in Carson City, Nevada, killing four people, including three members of the National Guard, and wounding seven others before fatally shooting himself.

The Kandahar massacre, also called the Panjwai massacre, was a mass murder that occurred in the early hours of 11 March 2012, when United States Army Staff Sergeant Robert Bales murdered 16 Afghan civilians and wounded six others in the Panjwayi District of Kandahar Province, Afghanistan. Nine of his victims were children, and eleven of the dead were from the same family. Some of the corpses were partially burned. Bales was taken into custody later that morning when he told authorities, "I did it".

Robert Bales is a former United States Army sniper who fatally shot or stabbed 16 Afghan civilians in a mass murder in Panjwayi District, Kandahar Province, Afghanistan, on March 11, 2012 – an event known as the Kandahar massacre.

The 2013 Hawija clashes relate to a series of violent attacks within Iraq, as part of the 2012–2013 Iraqi protests and Iraqi insurgency post-U.S. withdrawal. On 23 April, an army raid against a protest encampment in the city of Hawija, west of Kirkuk, led to dozens of civilian deaths and the involvement of several insurgent groups in organized action against the government, leading to fears of a return to a wide-scale Sunni–Shia conflict within the country. By 27 April, more than 300 people were reported killed and scores more injured in one of the worst outbreaks of violence since the U.S. withdrawal in December 2011.

Operation al-Shabah was launched in May 2013 by the Iraqi Army, with the stated aim of severing contact between the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant and the al-Nusra Front in Syria by clearing militants from the border area with Syria and Jordan.

The Washington Navy Yard shooting occurred on September 16, 2013, when 34-year-old Aaron Alexis fatally shot 12 people and injured three others in a mass shooting at the headquarters of the Naval Sea Systems Command (NAVSEA) inside the Washington Navy Yard in southeast Washington, D.C. The attack took place in the Navy Yard's Building 197; it began around 8:16 a.m. EDT and ended when police killed Alexis around 9:25 a.m. It was the second-deadliest mass murder on a U.S. military base, behind the 2009 Fort Hood shooting.

On 25 May 2015, a mass murder took place at the Bouchoucha military base in Tunis. A Tunisian soldier, later identified as Corporal Mehdi Jemaii, who was forbidden from carrying weapons, stabbed a soldier, then took his weapon. He then opened fire on soldiers during a flag-raising ceremony, killing seven and wounding ten, including one seriously injured who died on May 31, before he was killed during an exchange of gunfire.

On July 7, 2016, Micah Xavier Johnson ambushed a group of police officers in Dallas, Texas, shooting and killing five officers, and injuring nine others. Two civilians were also wounded. Johnson was an Army Reserve Afghan War veteran and was angry over police shootings of black men. The shooting happened at the end of a protest against the police killings of Alton Sterling in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and Philando Castile in Falcon Heights, Minnesota, which had occurred in the preceding days.