The Rodman gun is any of a series of American Civil War–era columbiads designed by Union artillery officer Thomas Jackson Rodman (1815–1871). The guns were designed to fire both shot and shell. These heavy guns were intended to be mounted in seacoast fortifications. 8-inch, 10-inch, 13-inch, 15-inch, and 20-inch bore Rodman guns were produced. Other than size, the guns were all nearly identical in design, with a curving bottle shape, a large flat cascabels, and ratchets or sockets for the elevating mechanism. Rodman guns were true guns that did not have a howitzer-like powder chamber, as did many earlier columbiads. Rodman guns differed from all previous artillery because they were hollow cast, a new technology that Rodman developed that resulted in cast-iron guns that were much stronger than their predecessors.

The Parrott rifle was a type of muzzle-loading rifled artillery weapon used extensively in the American Civil War.

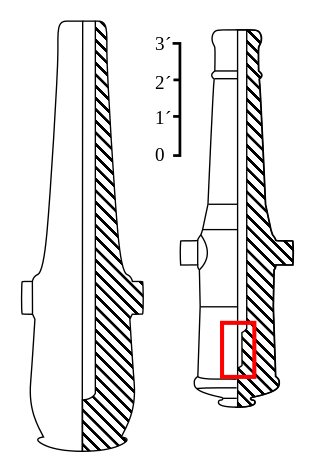

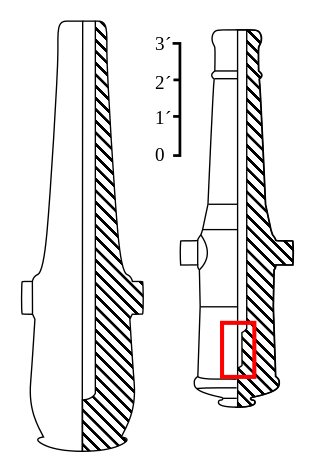

Dahlgren guns were muzzle-loading naval gun designed by a United States Navy Rear Admiral John A. Dahlgren, mostly used in the American Civil War. Dahlgren's design philosophy evolved from an accidental explosion in 1849 of a 32 lb (14.5 kg) gun being tested for accuracy, killing a gunner. He believed a safer, more powerful naval cannon could be designed using more scientific design criteria. Dahlgren guns were designed with a smooth curved shape, equalizing strain and concentrating more weight of metal in the gun breech where the greatest pressure of expanding propellant gases needed to be met to keep the gun from bursting. Because of their rounded contours, Dahlgren guns were nicknamed "soda bottles", a shape which became their most identifiable characteristic.

The Brooke rifle was a type of rifled, muzzle-loading naval and coast defense gun designed by John Mercer Brooke, an officer in the Confederate States Navy. They were produced by plants in Richmond, Virginia, and Selma, Alabama, between 1861 and 1865 during the American Civil War. They served afloat on Confederate ships and ashore in coast defense batteries operated by the Confederate States Army.

Field artillery in the American Civil War refers to the artillery weapons, equipment, and practices used by the artillery branch to support infantry and cavalry forces in the field. It does not include siege artillery, use of artillery in fixed fortifications, coastal or naval artillery. It also does not include smaller, specialized artillery pieces classified as infantry guns.

A muzzle-loading rifle is a muzzle-loaded small arm that has a rifled barrel rather than a smoothbore, and is loaded from the muzzle of the barrel rather than the breech. Historically they were developed when rifled barrels were introduced by the 1740ies, which offered higher accuracy than the earlier smoothbores. The American longrifle evolved from the German "Jäger" rifle; a popularly recognizable form of the "muzzleloader" was the Kentucky Rifle. Although by definition they must be reloaded after each shot in a time-consuming fashion, they are still produced for hunting.

Siege artillery is heavy artillery primarily used in military attacks on fortified positions. At the time of the American Civil War, the U.S. Army classified its artillery into three types, depending on the gun's weight and intended use. Field artillery were light pieces that often traveled with the armies. Siege and garrison artillery were heavy pieces that could be used either in attacking or defending fortified places. Seacoast artillery were the heaviest pieces and were intended to be used in permanent fortifications along the seaboard. They were primarily designed to fire on attacking warships. The distinctions are somewhat arbitrary, as field, siege and garrison, and seacoast artillery were all used in various attacks and defenses of fortifications. This article will focus on the use of heavy artillery in the attack of fortified places during the American Civil War.

The Wiard rifle refers to several weapons invented by Norman Wiard, most commonly a semi-steel light artillery piece in six-pounder and twelve-pounder calibers. About 60 were manufactured between 1861 and 1862 during the American Civil War, at O'Donnell's Foundry, New York City: "although apparently excellent weapons, [they] do not seem to have been very popular". Wiard also designed a rifled steel version of the Dahlgren boat howitzer, among other gun types. Further, Wiard unsuccessfully attempted to develop a 15 in (381 mm) rifled gun for the US Navy and proposed a 20 in (510 mm) gun. In 1881 he unsuccessfully proposed various "combined rifle and smoothbore" weapon conversions of Rodman guns and Parrott rifles.

James rifle is a generic term to describe any artillery gun rifled to the James pattern for use in the American Civil War, as used in some period documentation. Charles T. James developed a rifled projectile and rifling system. Modern authorities such as Warren Ripley and James Hazlett have suggested that the term "James rifle" only properly applies to 3.8 in (97 mm) bore field artillery pieces rifled to fire James' projectiles. They contend that the term does not apply to smoothbores that were later rifled to take the James projectiles in 3.67 in (93 mm) caliber or other calibers, and that those should instead be referred to as "Rifled 6 pounder", etc. The rifle was created in 1861.

Blakely rifle or Blakely gun is the name of a series of rifled muzzle-loading cannon designed by British army officer Captain Theophilus Alexander Blakely in the 1850s and 1860s. Blakely was a pioneer in the banding and rifling of cannon but the British army declined to use Blakely's design. The guns were mostly sold to Russia and the Confederacy during the American Civil War. Blakely rifles were imported by the Confederacy in larger numbers than other Imported English cannon. The State of Massachusetts bought eight 9 in (23 cm) and four 11 in (28 cm) models.

Sylvanus Sawyer was a United States inventor.

The M1841 6-pounder field gun was a bronze smoothbore muzzleloading cannon that was adopted by the United States Army in 1841 and used from the Mexican–American War to the American Civil War. It fired a 6.1 lb (2.8 kg) round shot up to a distance of 1,523 yd (1,393 m) at 5° elevation. It could also fire canister shot and spherical case shot (shrapnel). The cannon proved very effective when employed by light artillery units during the Mexican–American War. The cannon was used during the early years of the American Civil War, but it was soon outclassed by newer field guns such as the M1857 12-pounder Napoleon. In the U.S. Army, the 6-pounders were replaced as soon as more modern weapons became available and none were manufactured after 1862. However, the Confederate States Army continued to use the cannon for a longer period because the lesser industrial capacity of the South could not produce new guns as fast as the North.

The M1841 12-pounder field howitzer was a bronze smoothbore muzzle-loading artillery piece that was adopted by the United States Army in 1841 and employed during the Mexican–American War and the American Civil War. It fired a 8.9 lb (4.0 kg) shell up to a distance of 1,072 yd (980 m) at 5° elevation. It could also fire canister shot and spherical case shot. The howitzer proved effective when employed by light artillery units during the Mexican–American War. The howitzer was used throughout the American Civil War, but it was outclassed by the 12-pounder Napoleon which combined the functions of both field gun and howitzer. In the U.S. Army, the 12-pounder howitzers were replaced as soon as more modern weapons became available. Though none were manufactured after 1862, the weapon was not officially discarded by the U.S. Army until 1868. The Confederate States of America also manufactured and employed the howitzer during the American Civil War.

The 10-pounder Parrott rifle, Model 1861 was a muzzle-loading rifled cannon made of cast iron that was adopted by the United States Army in 1861 and often used in field artillery units during the American Civil War. Like other Parrott rifles, the gun breech was reinforced by a distinctive band made of wrought iron. The 10-pounder Parrott rifle was capable of firing shell, shrapnel shell, canister shot, or solid shot. Midway through the war, the Federal government discontinued the 2.9 in (74 mm) version in favor of a 3.0 in (76 mm) version. Despite the reinforcing band, the guns occasionally burst without warning, which endangered the gun crews. The Confederate States of America manufactured a number of successful copies of the gun.

The 20-pounder Parrott rifle, Model 1861 was a cast iron muzzle-loading rifled cannon that was adopted by the United States Army in 1861 and employed in field artillery units during the American Civil War. As with other Parrott rifles, the gun breech was reinforced by a distinctive wrought iron reinforcing band. The gun fired a 20 lb (9.1 kg) projectile to a distance of 1,900 yd (1,737 m) at an elevation of 5°. The 20-pounder Parrott rifle could fire shell, shrapnel shell, canister shot, and more rarely solid shot. In spite of the reinforcing band, the 20-pounder earned a dubious reputation for bursting without warning, killing or injuring gunners. The Confederate States of America also manufactured copies of the gun.

The 14-pounder James rifle or James rifled 6-pounder or 3.8-inch James rifle was a bronze muzzle-loading rifled cannon that was employed by the United States Army and the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War. It fired a 14 lb (6.4 kg) solid shot up to a distance of 1,530 yd (1,400 m) at 5° elevation. It could also fire canister shot and common shell. Shortly before the war broke out, the U.S. Army adopted a plan to convert M1841 6-pounder field guns from smoothbore to rifled artillery. Rifling the existing 6-pounders would both improve the gun's accuracy and increase the weight of the shell. There were two major types produced, both were bronze with a bore (caliber) of 3.8 in (97 mm) that would accommodate ammunition designed by Charles Tillinghast James. The first type looked exactly like an M1841 6-pounder field gun. The second type had a longer tube with a smooth exterior profile similar to a 3-inch Ordnance rifle. At first the rifles were quite accurate. However, it was discovered that the bronze rifling quickly wore out and accuracy declined. None of the rifles were manufactured after 1862, and many were withdrawn from service, though some artillery units employed the guns until the end of the war.

The M1841 24-pounder howitzer was a bronze smoothbore muzzle-loading artillery piece adopted by the United States Army in 1841 and employed from the Mexican–American War through the American Civil War. It fired a 18.4 lb (8.3 kg) shell to a distance of 1,322 yd (1,209 m) at 5° elevation. It could also fire canister shot and spherical case shot. The howitzer was designed to be employed in a mixed battery with 12-pounder field guns. By the time of the American Civil War, the 24-pounder howitzer was superseded by the 12-pounder Napoleon, which combined the functions of both field gun and howitzer. The 24-pounder howitzer's use as field artillery was limited during the conflict and production of the weapon in the North ended in 1863. The Confederate States of America manufactured a few 24-pounder howitzers and imported others from the Austrian Empire.

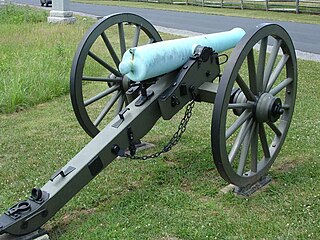

The M1857 12-pounder Napoleon or Light 12-pounder gun or 12-pounder gun-howitzer was a bronze smoothbore muzzle-loading artillery piece that was adopted by the United States Army in 1857 and extensively employed in the American Civil War. The gun was the American-manufactured version of the French canon obusier de 12 which combined the functions of both field gun and howitzer. The weapon proved to be simple to produce, reliable, and robust. It fired a 12.03 lb (5.5 kg) round shot a distance of 1,619 to 1,680 yd at 5° elevation. It could also fire canister shot, common shell, and spherical case shot. The 12-pounder Napoleon outclassed and soon replaced the M1841 6-pounder field gun and the M1841 12-pounder howitzer in the U.S. Army, while replacement of these older weapons was slower in the Confederate States Army. A total of 1,157 were produced for the U.S. Army, all but a few in the period 1861–1863. The Confederate States of America utilized captured U.S. 12-pounder Napoleons and also manufactured about 500 during the war. The weapon was named after Napoleon III of France, who helped develop the weapon.

The M1844 32-pounder howitzer was a bronze smoothbore muzzle-loading artillery piece adopted by the United States Army in 1844 and employed during the American Civil War. It fired a 25.6 lb (11.6 kg) common shell to a distance of 1,504 yd (1,375.3 m) at 5° elevation. It also fired canister shot and spherical case shot. The howitzer was originally designed to be used in a mixed battery with 12-pounder field guns. However, at the time of the American Civil War, the howitzer was replaced by the M1857 12-pounder Napoleon, which combined the functions of both field gun and howitzer. Only a few 32-pounder howitzers were produced, and they were used sparingly as field artillery during the Civil War because of the weapon's great weight.