Related Research Articles

Rav Ashi (352–427) was a Babylonian Jewish rabbi, of the sixth generation of amoraim. He reestablished the Academy at Sura and was the first editor of the Babylonian Talmud.

Amoraim refers to Jewish scholars of the period from about 200 to 500 CE, who "said" or "told over" the teachings of the Oral Torah. They were primarily located in Babylonia and Ancient Palestine. Their legal discussions and debates were eventually codified in the Gemara. The Amoraim followed the Tannaim in the sequence of ancient Jewish scholars. The Tannaim were direct transmitters of uncodified oral tradition; the Amoraim expounded upon and clarified the oral law after its initial codification.

Johanan bar Nappaha was a leading rabbi in the early era of the Talmud. He belonged to the second generation of amoraim.

Rabbah bar Naḥmani was a Jewish Talmudist known throughout the Talmud simply as Rabbah. He was a third-generation amora who lived in Sassanian Babylonia.

Abba ben Joseph bar Ḥama, who is exclusively referred to in the Talmud by the name Rava, was a Babylonian rabbi who belonged to the fourth generation of amoraim. He is known for his debates with Abaye, and is one of the most often cited rabbis in the Talmud.

Rav Pappa was a Babylonian rabbi, of the fifth generation of amoraim.

Rabbi Zeira, known before his semicha as Rav Zeira and known in the Jerusalem Talmud as Rabbi Ze'era, was a Jewish Talmudist, of the third generation of amoraim, who lived in the Land of Israel.

Bevai bar Abaye was a Jewish Talmudist who lived in Babylonia, known as an amora of the fourth and fifth amoraic generations.

Rav Huna was a Jewish Talmudist and Exilarch who lived in Babylonia, known as an amora of the second generation and head of the Academy of Sura; he was born about 216 CE and died in 296–297 CE or in 290 CE.

Rav Ḥisda was a Jewish Talmudist who lived in Kafri, Asoristan in Lower Mesopotamia near what is now the city of Najaf, Iraq. He was an amora of the third generation, and is mentioned frequently in the Talmud.

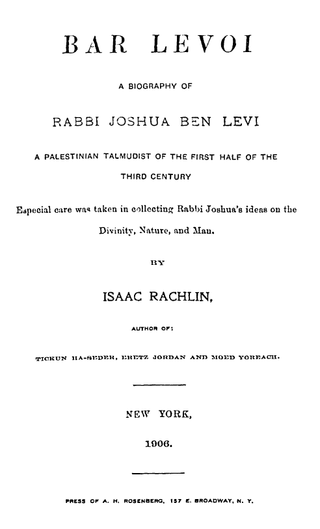

Joshua ben Levi was an amora, a scholar of the Talmud, who lived in the Land of Israel in the first half of the third century. He lived and taught in the city of Lod. He was an elder contemporary of Johanan bar Nappaha and Resh Lakish, who presided over the school in Tiberias. With Johanan bar Nappaha, he often engaged in homiletic exegetical discussions.

Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak was a Babylonian rabbi, of the fourth and fifth generations of amoraim.

Rabbah bar bar Hana was a Jewish Talmudist who lived in Babylonia, known as an Amora of the second generation.

Rav Joseph bar Hama was a Babylonian rabbi of the third generation of amoraim.

Rav Huna Kamma was a rabbi of the 2nd century AD and Babylonian Exilarch, allegedly descending from King [David]. The Seder Olam Zutta refers to him as "Anani", both names being a derivative of "Hananiah". The exact time of his tenure as exilarch is unknown, but it was estimated to have been between 170 and 210 AD.

Rav Huna bar Natan (Hebrew: הונא בר נתן, read as Rav Huna bereih deRav Natan was a Babylonian rabbi and exilarch, of the fifth and sixth generations of amoraim.

For other Amoraic sages of Babylonia with the name "Rav Kahana", see Rav Kahana.

Jeremiah bar Abba was a Babylonian rabbi who lived around the mid-3rd century. He is cited many times in the Jerusalem Talmud, where he is mentioned simply as Rav Jeremiah, without his patronymic name.

Rav Isaac son of Rav Judah was a Babylonian rabbi who lived in the 4th century.

Rav Anan was a Babylonian rabbi of the third century.

References

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Kiddushin 72a,b; Genesis Rabbah 63:2

- ↑ Jerusalem Talmud Bava Metzia 3a; Babylonian Talmud Berakhot 42b–43a

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Yevamot 110b

- ↑ Psalm 101:2

- ↑ Jerusalem Talmud Taanit 67a; compare Babylonian Talmud Taanit 20b

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Berakhot 20a

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Taanit 16a; compare Tosefta Taanit 1:8

- ↑ Jerusalem Talmud Taanit 67a

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Taanit 20b

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Taanit 8a; Yevamot 61b; Sanhedrin 81a–b

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud Bava Batra 22a

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain : S. Mendelsohn (1901–1906). "Adda b. Ahabah". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia . New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain : S. Mendelsohn (1901–1906). "Adda b. Ahabah". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia . New York: Funk & Wagnalls.