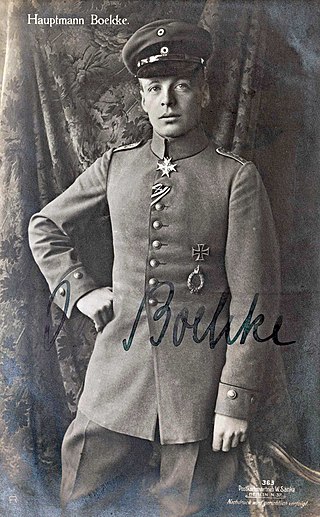

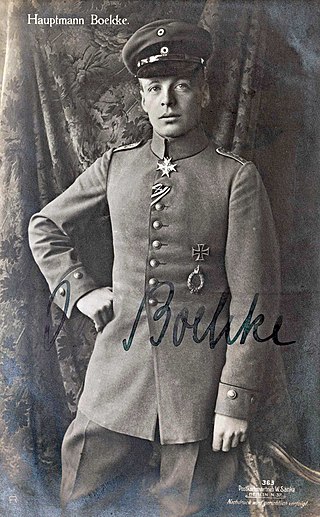

Oswald Boelcke PlM was a World War I German professional soldier and pioneering flying ace credited with 40 aerial victories. Boelcke is honored as the father of the German fighter air force, and of air combat as a whole. He was a highly influential mentor, patrol leader, and tactician in the first years of air combat, 1915 and 1916.

A flying ace, fighter ace or air ace is a military aviator credited with shooting down five or more enemy aircraft during aerial combat. The exact number of aerial victories required to officially qualify as an ace is varied but is usually considered to be five or more.

Julius Buckler was a German First World War fighter ace credited with 36 victories during the war. He shot down 29 enemy airplanes and seven observation balloons; two other victories went unconfirmed. He was one of only four German fighter aces to win Germany's highest decorations for valor for both enlisted man and officer.

LeutnantFriedrich Theodor Noltenius was a German flying ace during the First World War, with a total of 21 official victories. From July 1914 to July 1917, he served with distinction as an artilleryman. He transferred to the Luftstreitkräfte and became a fighter pilot. After his aerial combat career began with a horrifying incident, Noltenius began shooting down enemy observation balloons and airplanes on 10 August 1918. His battle claims were sometimes unsuccessfully disputed with other pilots, including his commanding officers. Despite the resulting transfers between units, Noltenius continued his success, being credited with his 21st victory on 4 November 1918. Only the war's end a week later barred him from receiving Germany's highest award for valor, the Pour le Mérite.

Otto Kissenberth was a German flying ace of World War I credited with 20 aerial victories. He was a prewar mechanical engineer who joined the German air service in 1914. After being trained and after serving as a reconnaissance pilot, he became one of the first German fighter pilots, flying with Kampfeinsitzerkommando KEK Einsisheim. He scored six victories with this unit as it morphed into a fighter squadron, Jagdstaffel 16. His success brought him command of Jagdstaffel 23 on 4 August 1917. He would run his victory tally to 20, downing his final victim using a captured British Sopwith Camel on 20 May 1918. Nine days later, a crash while flying the Camel ended Kissenberth's combat career. His injuries were severe enough he was not returned to combat, instead being assigned to command Schleissheim's flying school. Although Otto Kissenberth survived the war, he died soon after in a mountaineering accident on 2 August 1919.

The following are lists of World War I flying aces. Historically, a flying ace was defined as a military aviator credited with shooting down five or more enemy aircraft during aerial combat. The term was first used by French newspapers, describing Adolphe Pégoud as l'as, after he downed seven German aircraft.

This article explores confirmation and overclaiming of aerial victories during World War II. In aerial warfare, the term overclaiming describes a combatant that claims the destruction of more enemy aircraft than actually achieved. The net effect is that the actual losses and claimed victories are unequal, and that the claiming side is inaccurately reporting their combat achievements, thereby potentially undermining their credibility to all parties participating and observing the war.

Rittmeister Carl Bolle was a German fighter ace with 36 aerial victories during World War I and a recipient of the Order Pour le Mérite, Prussia's highest award for bravery. He became a Jagdstaffel commander during that war, and an advisor to the Luftwaffe during World War II.

LeutnantKurt Wintgens was a German World War I fighter ace. He was the first fighter pilot to score an aerial victory with a synchronized machine gun. Wintgens was the recipient of the Iron Cross and the Pour le Mérite.

OberleutnantFritz Otto Bernert was a leading German fighter ace of World War I. After being invalided from infantry duty after his fourth wound, Bernert joined the aviation branch. After pilot training, he scored 27 victories between 17 April 1916 and 7 May 1917 despite being essentially one-armed and wearing pince-nez. Among his 15 victories during Bloody April were five scored in 20 minutes on 13 April 1917. He was promoted to squadron command, first of Jagdstaffel 6, then of Jagdstaffel 2. Removed from command on 18 August 1918 by wounds and illness, he died of influenza on 18 October 1918.

Leutnant Georg von Hantelmann was a German fighter ace credited with winning 25 victories during World War I. It was notable that these victories included three opposing aces shot down within the same week in September 1918–David Putnam, Maurice Boyau, and Joseph Wehner.

Leutnant Fritz Höhn was a German World War I fighter ace credited with 21 victories. He had worked his way up to being a fighter squadron commander and was eligible for the German Empire's highest award for heroism, the Blue Max, when he was killed in action on 3 October 1918.

Doctor OberleutnantOtto Schmidt HOH, IC was a German World War I fighter ace credited with 20 aerial victories, including eight against enemy observation balloons. He commanded three different jagdstaffeln (squadrons) as well as a jagdgruppe.

Leutnant Josef Karl Ernst Raesch was a World War I flying ace credited with seven aerial victories. Two of his victories were over other aces, Guy Wareing and Ernest Charles Hoy.

OberleutnantHans Berr was a German professional soldier and World War I flying ace. At the start of the First World War, he served in a scout regiment until severely wounded; he then transferred to aviation duty. Once trained as a pilot, he helped pioneer the world's first dedicated fighter airplane, the Fokker Eindecker "flying gun". Flying one, Berr shot down two enemy airplanes in March 1916 as his contribution to the Fokker Scourge. Berr was then chosen to command one of the world's original fighter squadrons, Jagdstaffel 5. Leading his pilots by example, Berr scored eight more victories in a four week span in October - November 1916 while his pilots began to compile their own victories. Hans Berr was awarded Germany's highest military honor, the Pour le Merite, on 4 December 1916. During a 6 April 1917 dogfight, Berr and his wingman mortally collided.

Royal Prussian Jagdstaffel 15, commonly abbreviated to Jasta 15, was a "hunting group" of the Luftstreitkräfte, the air arm of the Imperial German Army during World War I. The unit would score over 150 aerial victories during the war, at the expense of seven killed in action, two killed in flying accidents, three wounded in action, one injured in a flying accident, and two taken prisoner of war.

Royal Prussian Jagdstaffel 12 was a World War I "hunting group" of the Luftstreitkräfte, the air arm of the Imperial German Army during World War I. As one of the original German fighter squadrons, the unit would score 155 aerial victories during the war, at the expense of seventeen killed in action, eight wounded in action, and one taken prisoner of war.

Oberst Paul Aue was a World War I flying ace from the Kingdom of Saxony in the German Empire. Partial records of his early aviation career credit him with 10 aerial victories. He would join the nascent Luftwaffe during the 1930s and serve Germany through World War II. He died in a Soviet prison camp in 1945.

Jagdgeschwader II was the Imperial German Air Service's second fighter wing. Established because of the great success of Manfred von Richthofen's preceding Jagdgeschwader I wing, Jagdgeschwader II and Jagdgeschwader III were founded on 2 February 1918. JG II was assigned four squadrons nominally equipped with 14 aircraft each. The new wing was supposed to be fully operational in time for an offensive slated for 21 March 1918. Named to raise and lead it was 23-victory flying ace Hauptmann Adolf von Tutschek. However, he was killed in action on 15 March 1918.

Jagdgeschwader III was a fighter wing of the Imperial German Air Service during World War I. It was founded on 2 February 1918, as a permanent consolidation of four established jagdstaffeln —2, 26, 27, and 36. JG III was formed as a follow-on of Manfred von Richthofen's highly successful Jagdgeschwader I. With a nominal strength of 56 aircraft, JG III would be under direct orders of an Armee headquarters. The German General Staff was planning a German spring offensive to begin on 21 March 1918, and wanted to assign a fighter wing to each of the three Armees involved in the assault. An experienced flying ace with 22 victories, Oberleutnant Bruno Loerzer, was appointed to command JG III.