Julius Arigi was a flying ace of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in World War I with a total of 32 credited victories. His victory total was second only to Godwin von Brumowski. Arigi was considered a superb natural pilot. He was also a technical innovator responsible for engineering changes in the aircraft he flew.

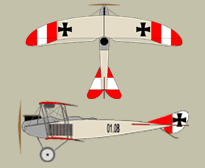

The Hansa-Brandenburg G.I was a bomber aircraft used to equip the Austro-Hungarian aviation corps in World War I. It was a mostly conventional large, three-bay biplane with staggered wings of slightly unequal span. The pilot and bombardier sat in a large open cockpit at the nose of the aircraft, with a second open cockpit for a gunner in a dorsal position behind the wings. An unusual feature was the placement of the twin tractor engines. While the normal practice of the day was to mount these to the wings, either directly or on struts, the G.I had the engines mounted to the sides of the fuselage on lattices of steel struts. This arrangement added considerable weight to the aircraft and transmitted a lot of vibration to the airframe.

The Italian Corpo Aeronautico Militare was formed as part of the Regio Esercito on 7 January 1915, incorporating the Aviators Flights Battalion (airplanes), the Specialists Battalion (airships) and the Ballonists Battalion. Prior to World War I, Italy had pioneered military aviation in the Italo-Turkish War during 1911–1912. Its army also contained one of the world's foremost theorists about the future of military aviation, Giulio Douhet; Douhet also had a practical side, as he was largely responsible for the development of Italy's Caproni bombers starting in 1913. Italy also had the advantage of a delayed entry into World War I, not starting the fight until 24 May 1915, but took no advantage of it so far as aviation was concerned.

Godwin Karol Marian von Brumowsky was the most successful fighter ace of the Austro-Hungarian Air Force during World War I. He was officially credited with 35 air victories, with 8 others unconfirmed because they fell behind Allied lines. Just before the war ended, Brumowski rose to command of all his country's fighter aviation fighting Italy on the Isonzo front.

Hauptmann (Captain) Benno Fiala Ritter von Fernbrugg was an Austro-Hungarian fighter ace with 28 victories to his credit during World War I. He was the third ranking ace of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. His honours and decorations included the Order of the Iron Crown, Order of Leopold, Military Merit Cross, Military Merit Medal, Gold Medal for Bravery (Austria-Hungary) and the Iron Cross. He was also a technical innovator who pioneered the use of machine guns, radios, and cameras in airplanes. His forty-year aviation career also included aircraft manufacture, airport management, and the establishment of commercial airlines.

Oberleutnant Frank Linke-Crawford, was the fourth-ranking ace of the Austro-Hungarian Air Force during World War I, with 27 victories.

FeldwebelJulius Busa was an Austro-Hungarian World War I flying ace credited with five aerial victories during 1916. He was also notable for twice surviving direct hits by antiaircraft shells, saving his aircraft and aerial observer on both occasions. Busa scored all his aerial victories while engaged in general purpose missions in two-seater reconnaissance airplanes. His valor would be rewarded with Austria-Hungary's highest award for non-commissioned officers, the Gold Medal for Bravery. He also won three Silver Medals for Bravery—two First Class and one Second Class. Busa was killed in action by Francesco Baracca on 13 May 1917.

OberleutnantRudolf Szepessy-Sokoll Freiherr von Negyes et Reno was a Hungarian World War I flying ace credited with five aerial victories. He began his military career as a cavalryman as the war began in 1914. After winning the Silver Medal for Bravery and being promoted into the officers' ranks, he transferred to the Austro-Hungarian Aviation Troops in mid-1915 as an aerial observer. On 14 February 1916, while participating in a historic strategic bombing raid on Milan, he scored his first aerial victory. After shooting down another airplane and an observation balloon, Szepessy-Sokoll was transferred to a fighter unit after pilot training. After shooting down a pair of Macchi L.3s on 5 November 1917, he was killed in action the next day.

FeldwebelAndreas Dombrowski was an Austro-Hungarian World War I flying ace credited with six aerial victories scored on three different fronts. He was conscripted into the Austro-Hungarian military in 1915. Dombrowski underwent pilot's training, gaining his license in June 1916. Posted to the Russian Front during the Brusilov Offensive to fly reconnaissance, he was credited with his first victory on 17 August 1916. In September, 1916 he was transferred to the Romanian Front. Still flying a reconnaissance aircraft, he fought four more successful engagements during 1917, becoming an ace. Transferred to the Italian Front in April 1918, he flew an Albatros D.III for his former observer, Karl Patzelt. On 4 May 1918, Dombrowski scored his sixth and final victory, then took a bullet to the face and crashlanded. Once healed, he went to a photographic reconnaissance unit for the rest of the war.

Johann Frint was an Austro-Hungarian flying ace during World War I and professional soldier credited with six aerial victories while flying as an aerial observer. Crippled as an infantry officer in November 1914, Frint volunteered for the Austro-Hungarian Aviation Troops. He scored his victories on the Italian Front from the rear seat of two-seater reconnaissance aircraft with a variety of pilots, including a triple victory while being flown by his commanding officer, Heinrich Kostrba. Rewarded with the Order of the Iron Crown and Military Merit Medal, Frint became a mediocre pilot. He was entrusted with successive commands of a number of squadrons before dying in an airplane crash in 1918.

Hauptmann Karl Nikitsch was a professional soldier who served, in succession, the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the First Austrian Republic. His First World War service in the Austro-Hungarian Imperial and Royal Aviation Troops was marked by his abilities in organizing, staffing, and commanding flying squadrons. He also became a flying ace credited with six aerial victories Postwar, he commanded the Austrian Flugpolizei.

Oberleutnant Josef Pürer (1894-1918) was an Austro-Hungarian World War I flying ace credited with six aerial victories. A volunteer for the artillery when the war began, he fought for two years on the Russian Front. He was commissioned as an officer on 1 January 1916; later that year he transferred to the Austro-Hungarian Aviation Troops. He served as an aerial observer in northern Italy until early 1918. After scoring six aerial victories, he was trained as a fighter pilot by 11 July 1918. He was killed in action by Sidney Cottle on 31 August 1918.

Hauptmann József von Maier, after 1922 József Modory, was an Austro-Hungarian World War I flying ace credited with seven aerial victories.

Károly Kaszala was an Austro-Hungarian World War I flying ace credited with eight aerial victories, thus winning his nation's highest honor, the Gold Medal for Bravery. Joining the military in 1914, he volunteered for aviation duty after recruit training. After pilot's training, he was posted to Fliegerkompanie 14, where he refused to fly his assigned aircraft. He was transferred for his insubordination; as he gained experience in his new unit, he and his observers managed to score three aerial victories from his reconnaissance two-seater. He was then upgraded to single-seat fighters, winning four more victories by the end of 1917. He was then posted to test pilot duties until war's end. In addition to the Gold Medal for Bravery, he had won three Silver Medals for Bravery and a German Iron Cross.

Oberst Adolf Heyrowsky, was a career officer in the Austro-Hungarian military who turned to aviation. He became an accredited flying ace during World War I, with twelve aerial victories scored despite the fact he was a reconnaissance pilot instead of flying fighters. The units he flew in and commanded had long range recon and ground attacks as their primary mission.

Kurt Gruber was an Austro-Hungarian flying ace during the First World War who held the rank of Offiziersstellvertreter. He was credited with eleven aerial victories, 5 shared with other pilots.

Oberleutnant Ernst Strohschneider was an Austro-Hungarian flying ace during World War I. He was credited with 15 confirmed aerial victories during his rise to the simultaneous command of two fighter squadrons. He died in a flying accident on 21 March 1918.

Feldwebel Stefan Fejes was an Austro-Hungarian flying ace credited with 16 confirmed and 4 unconfirmed aerial victories during World War I. By war's end, he had not only received numerous decorations, he had been personally promoted by his emperor.

Stabsfeldwebel Ferdinand Udvardy was a Hungarian conscript into the military of the Austro-Hungarian Empire who became a flying ace credited with nine aerial victories. Upon the dissolution of Austria-Hungary, Udvardy became a Hungarian citizen, and in the aftermath of World War I, defended his new nation against invasion.

Oberleutnant Georg Kenzian Edler von Kenzianshausen followed his father's profession of arms, and served the Austro-Hungarian Empire during World War I. He became a fighter ace, scoring eight aerial victories. After the dissolution of Austria-Hungary in the aftermath of World War I, he became a citizen of German Austria and defended his new nation against invasion.