Timor is an island at the southern end of Maritime Southeast Asia, in the north of the Timor Sea. The island is divided between the sovereign states of East Timor in the eastern part and Indonesia in the western part. The Indonesian part, known as West Timor, constitutes part of the province of East Nusa Tenggara. Within West Timor lies an exclave of East Timor called Oecusse District. The island covers an area of 30,777 square kilometres. The name is a variant of timur, Malay for "east"; it is so called because it lies at the eastern end of the Lesser Sunda Islands. Mainland Australia is less than 500 km away, separated by the Timor Sea.

West Timor is an area covering the western part of the island of Timor, except for the district of Oecussi-Ambeno. Administratively, West Timor is part of East Nusa Tenggara Province, Indonesia. The capital as well as its main port is Kupang. During the colonial period, the area was named Dutch Timor and was a centre of Dutch loyalists during the Indonesian National Revolution (1945–1949). From 1949 to 1975 it was named Indonesian Timor.

Portuguese Timor was a colonial possession of Portugal that existed between 1702 and 1975. During most of this period, Portugal shared the island of Timor with the Dutch East Indies.

Kupang, formerly known as Koepang or Coupang, is the capital of the Indonesian province of East Nusa Tenggara. At the 2020 Census, it had a population of 442,758; the official estimate as of mid-2023 was 466,632. It is the largest city and port on the island of Timor, and is a part of the Timor Leste–Indonesia–Australia Growth Triangle free trade zone. Geographically, Kupang is the southernmost city in Indonesia.

Larantuka is a kecamatan (district) and the seat of East Flores Regency, on the eastern end of Flores Island, East Nusa Tenggara, Indonesia. Like much of the region, Larantuka has a strong colonial Portuguese influence. The town had 37,348 inhabitants at the 2010 census and 40,828 at the 2020 census; the official estimate as at mid 2023 was 41,500. This overwhelmingly (95.4%) Roman Catholic area enjoys some international renown for its Holy Week celebrations.

Amabi was a traditional principality in West Timor in the currently East Nusa Tenggara province of Indonesia. From at least the 17th century to 1917, Amabi played a role in the rivalries between the Portuguese and Dutch colonials on Timor Island.

Sonbai was an Indonesian princely dynasty that reigned over various parts of West Timor from at least the 17th century until the 1950s. It was known as the most prestigious princedom of the Atoni people of West Timor, and is the subject of many myths and stories.

Lifau is a village and suco in the East Timor exclave of Oecusse District. The village is located west of the mouth of the Tono River. 1,938 people live in the suco.

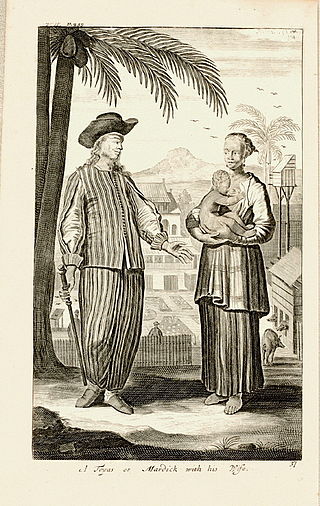

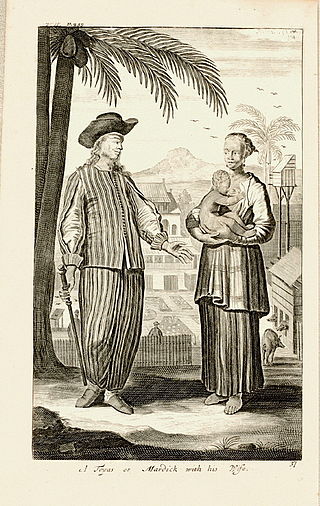

Topasses were a group of people led by the two powerful families – Da Costa and Hornay – that resided in Oecussi and Flores. The Da Costa families were descendants of Portuguese Jewish merchants and Hornay were Dutch.

Gaspar da Costa was the leader or tenente geral of the Portuguese-speaking Topasses, a Eurasian group that dominated much of the politics on Timor in the early modern period. He was largely responsible for the dramatic collapse of Portuguese power in West Timor, a process that laid the foundations for the modern division of Timor in an Indonesian and an independent part.

Wehali is the name of a traditional kingdom at the southern coast of Central Timor, now in Indonesia and East Timor. It is often mentioned together with its neighbouring sister kingdom, as Wewiku-Wehali (Waiwiku-Wehale). Wehali held a position of ritual seniority among the many small Timorese kingdoms.

Liurai is a ruler's title on Timor. The word is Tetun and literally means "surpassing the earth". It was originally associated with Wehali, a ritually central kingdom situated at the south coast of central Timor. The sacral lord of Wehali, the Maromak Oan enjoyed a ritually passive role, and he kept the liurai as the executive ruler of the land. In the same way, the rulers of two other important princedoms, Sonbai in West Timor and Likusaen (Liquica) in East Timor, were often referred as liurais, which indicated a symbolic tripartition of the island. In later history, especially in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the term liurai underwent a process of inflation. By this time it denoted any ruler in the Portuguese part of Timor, great or small. In the Dutch part in West Timor the title appears to have been restricted to the Sonbai and Wehali rulers. The rulers in the west were known by the Malay term raja, while there were internally used terms such as usif (lord) among the Dawan-speaking groups, and loro (sun) among the Tetun speakers.

Amanuban was a traditional princedom in West Timor, Indonesia. It lay in the regency (kabupaten) Timor Tengah Selatan. In the late colonial period, according to an estimate in 1930, Amanuban covered 2,075 square kilometers. The centre of the princedom since the 19th century was Niki-Niki. The population belongs to the Atoni group. Today they are predominantly Protestants, with a significant Catholic minority and some Muslims.

Sonbai Besar or Greater Sonbai was an extensive princedom of West Timor, in present-day Indonesia, which existed from 1658 to 1906 and played an important role in the history of Timor.

Sonbai Kecil or Lesser Sonbai was an Atoni princedom in West Timor, now included in Indonesia. It existed from 1658 to 1917, when it merged into a colonial creation, the zelfbesturend landschap Kupang.

Amarasi was a traditional princedom in West Timor, in present-day Indonesia. It had an important role in the political history of Timor during the 17th and 18th century, being a client state of the Portuguese colonialists, and later subjected to the Netherlands East Indies.

Portuguese Indonesians are native Indonesians with Portuguese ancestry or have had adopted Portuguese customs and some practices such as religion.

The Kingdom of Larantuka was a historical monarchy in present-day East Nusa Tenggara, Indonesia. It was one of the few, if not the only, indigenous Catholic polities in the territory of modern Indonesia. Acting as a tributary state of the Portuguese Crown, the Raja (King) of Larantuka controlled holdings on the islands of Flores, Solor, Adonara and Lembata. It was later purchased by Dutch East Indies from the Portuguese, prior to its annexation in 1904.

The Battle of Penfui took place on 9 November 1749 in the hillside of Penfui, near modern Kupang. A large Topass army was defeated by a numerically inferior Dutch East India Company force following the withdrawal of the former's Timorese allies from the battlefield, resulting in the death of the Topass leader Gaspar da Costa. Following the battle, both Topass and Portuguese influence on Timor declined, eventually leading to the formation of a boundary between Dutch and Portuguese Timor which precipitated into the modern border between West Timor and East Timor.