Fascism is a form of far-right, authoritarian ultranationalism characterized by dictatorial power, forcible suppression of opposition, and strong regimentation of society and of the economy, which came to prominence in early 20th-century Europe. The first fascist movements emerged in Italy during World War I, before spreading to other European countries. Opposed to anarchism, democracy, liberalism, and Marxism, fascism is placed on the far right-wing within the traditional left–right spectrum.

The term fellow traveller identifies a person who is intellectually sympathetic to the ideology of a political organization, and who co-operates in the organization's politics, without being a formal member of that organization. In the early history of the Soviet Union, the Bolshevik revolutionary and Soviet statesman Anatoly Lunacharsky coined the term poputchik and later it was popularized by Leon Trotsky to identify the vacillating intellectual supporters of the Bolshevik government. It was the political characterisation of the Russian intelligentsiya who were philosophically sympathetic to the political, social, and economic goals of the Russian Revolution of 1917, but who did not join the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. The usage of the term poputchik disappeared from political discourse in the Soviet Union during the Stalinist régime, but the Western world adopted the English term fellow traveller to identify people who sympathised with the Soviets and with Communism.

The raised fist, or the clenched fist, is a long standing image of mixed meaning, often a symbol of political solidarity. It is also a common symbol of communism, and can also be used as a salute to express unity, strength, or resistance.

Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee v. McGrath, 341 U.S. 123 (1951), was a United States Supreme Court case that held that groups could sue to challenge their inclusion on the Attorney General's List of Subversive Organizations. The decision was fractured on its reasoning, with each of the Justices in the majority writing separate opinions.

The Republican Fascist Party was a political party in Italy led by Benito Mussolini during the German occupation of Central and Northern Italy and was the sole legal and ruling party of the Italian Social Republic. It was founded as the successor to the National Fascist Party while incorporating anti-monarchism, as they considered King Victor Emmanuel III to be a traitor after his signing of the surrender to the Allies.

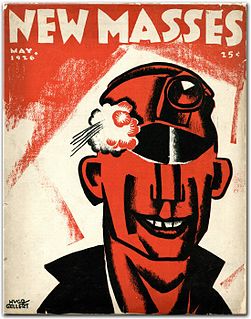

New Masses (1926–1948) was an American Marxist magazine closely associated with the Communist Party USA. It succeeded both The Masses (1912–1917) and The Liberator. New Masses was later merged into Masses & Mainstream (1948–1963). With the coming of the Great Depression in 1929 America became more receptive to ideas from the political Left and New Masses became highly influential in intellectual circles. The magazine has been called “the principal organ of the American cultural left from 1926 onwards."

The John Reed Clubs (1929-1935), often referred to as John Reed Club or JRC, were an American federation of local organizations targeted towards Marxist writers, artists, and intellectuals, named after the American journalist and activist John Reed. Established in the fall of 1929, the John Reed Clubs were a mass organization of the Communist Party USA which sought to expand its influence among radical and liberal intellectuals. The organization was terminated in 1935.

What constitutes a definition of fascism and fascist governments has been a complicated and highly disputed subject concerning the exact nature of fascism and its core tenets debated amongst historians, political scientists, and other scholars since Benito Mussolini first used the term in 1915. Historian Ian Kershaw once wrote that "trying to define 'fascism' is like trying to nail jelly to the wall".

The League of American Writers was an association of American novelists, playwrights, poets, journalists, and literary critics launched by the Communist Party USA (CPUSA) in 1935. The group included Communist Party members, and so-called "fellow travelers" who closely followed the Communist Party's political line without being formal party members, as well as individuals sympathetic to specific policies being advocated by the organization.

The Movement Against War and Fascism (MAWF) was founded in Australia in 1933, as an Australian chapter of the World Movement Against War established in 1932 by the Comintern. The international movement was instigated by Willi Münzenberg the German Comintern leader who founded a multitude of front organisations in his quest to spread the word and power of International Communism. The Australian movement set out to attract "fellow-travellers" and pacifists, and was relatively independent of the international organisation.

Jacob "Jake" Burck was a Polish-born Jewish-American painter, sculptor, and award-winning editorial cartoonist. Active in the Communist movement from 1926 as a political cartoonist and muralist, Burck quit the Communist Party after a visit to the Soviet Union in 1936, deeply offended by political demands there to manipulate his work.

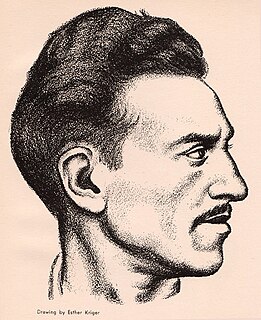

Joseph P. Lash was an American radical political activist, journalist, and author. A close friend of Eleanor Roosevelt, Lash won both the Pulitzer Prize for Biography and the National Book Award in Biography for Eleanor and Franklin (1971), the first of two volumes he wrote about the former First Lady.

A popular front is "any coalition of working-class and middle-class parties", including liberal and social-democratic ones, "united for the defense of democratic forms" against "a presumed Fascist assault". It has also been used to refer to political coalitions "sponsored and dominated by Communists as a device for gaining power". More generally, it is "a coalition especially of leftist political parties against a common opponent".

Anti-fascism is a political movement in opposition to fascist ideologies, groups and individuals. Beginning in European countries in the 1920s, it was at its most significant shortly before and during World War II, where the Axis powers were opposed by many countries forming the Allies of World War II and dozens of resistance movements worldwide. Anti-fascism has been an element of movements across the political spectrum and holding many different political positions such as anarchism, communism, pacifism, republicanism, social democracy, socialism and syndicalism as well as centrist, conservative, liberal and nationalist viewpoints.

The World Committee Against War and Fascism was an international organization sponsored by the Communist International, that was active in the struggle against Fascism in the 1930s. During this period Adolf Hitler came to power in Germany, Italy invaded Ethiopia and the Spanish Civil War broke out. Although some of the women involved were Communists whose priority was preventing attacks on the Soviet Union, many prominent pacifists with different ideologies were members or supporters of the committee. The World Committee sponsored subcommittees for Women and Students, and national committees in countries that included Spain, Britain, Mexico and Argentina. The Women's branches were particularly active and included feminist leaders such as Gabrielle Duchêne of France, Sylvia Pankhurst of Britain and Dolores Ibárruri of Spain.

Jolán Gross-Bettelheim (1900–1972) was a Hungarian artist who lived and worked in the United States from 1925 to 1956, before returning to Hungary.

Lviv Anti-Fascist Congress of Cultural Workers was an event that brought together the progressive intellectuals of Poland, Western Ukraine, and Western Belarus. It took place on May 16-17, 1936 in Lviv, being organized by the Communist Party of Poland along with the Communist Party of Western Ukraine in order to create the united front against Fascism.