The Ku Klux Klan, commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is the name of several historical and current American white supremacist, far-right terrorist organizations and hate groups. Various commentators, including Fergus Bordewich, have characterized the Klan as America's first terrorist group. Their primary targets, at various times and places, have been African Americans, Jews, and Catholics.

The United States Department of Justice (DOJ), also known as the Justice Department, is a federal executive department of the United States government tasked with the enforcement of federal law and administration of justice in the United States. It is equivalent to the justice or interior ministries of other countries. The department is headed by the U.S. attorney general, who reports directly to the president of the United States and is a member of the president's Cabinet. The current attorney general is Merrick Garland, who has served since March 2021.

The Radical Republicans were a political faction within the Republican Party originating from the party's founding in 1854—some six years before the Civil War—until the Compromise of 1877, which effectively ended Reconstruction. They called themselves "Radicals" because of their goal of immediate, complete, and permanent eradication of slavery in the United States. The Radical faction also included, though, very strong currents of Nativism, anti-Catholicism, and in favor of the Prohibition of alcoholic beverages. These policy goals and the rhetoric in their favor often made it extremely difficult for the Republican Party as a whole to avoid alienating large numbers of American voters from Irish Catholic, German-, and other White ethnic backgrounds. In fact, even German-American Freethinkers and Forty-Eighters who, like Hermann Raster, otherwise sympathized with the Radical Republicans' aims, fought them tooth and nail over prohibition.

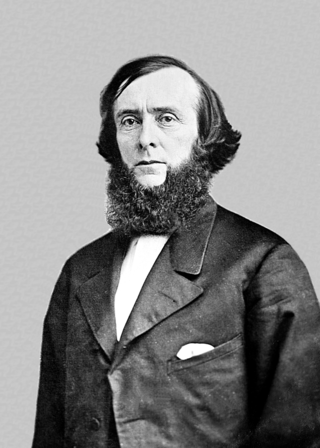

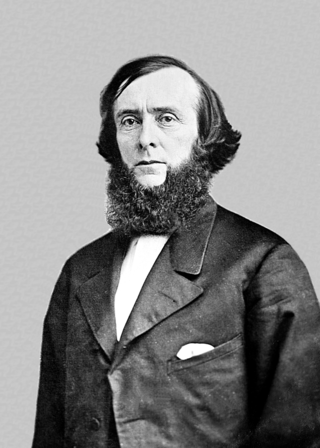

Benjamin Helm Bristow was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 30th U.S. Treasury Secretary and the first Solicitor General.

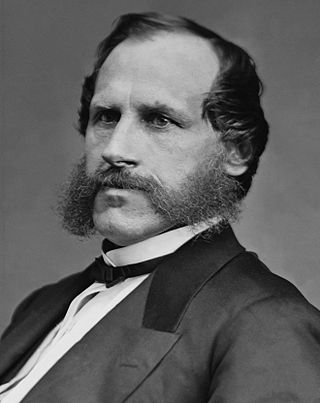

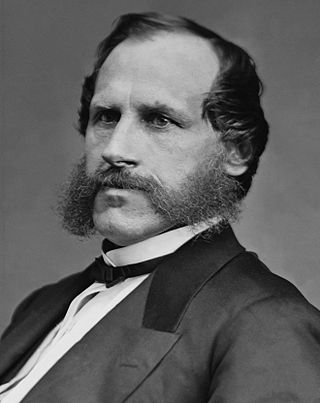

Edwards Pierrepont was an American attorney, reformer, jurist, traveler, New York U.S. Attorney, U.S. Attorney General, U.S. Minister to England, and orator. Having graduated from Yale in 1837, Pierrepont studied law and was admitted to the bar in 1840. During the American Civil War, Pierrepont was a Democrat, although he supported President Abraham Lincoln. Pierrepont initially supported President Andrew Johnson's conservative Reconstruction efforts having opposed the Radical Republicans. In both 1868 and 1872, Pierrepont supported Ulysses S. Grant for president. For his support, President Grant appointed Pierrepont United States Attorney in 1869. In 1871, Pierrepont gained the reputation as a solid reformer, having joined New York's Committee of Seventy that shut down Boss Tweed's corrupt Tammany Hall. In 1872, Pierrepont modified his views on Reconstruction and stated that African American freedman's rights needed to be protected.

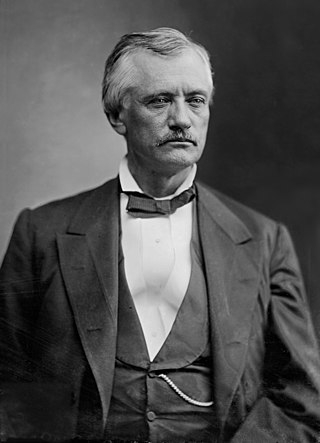

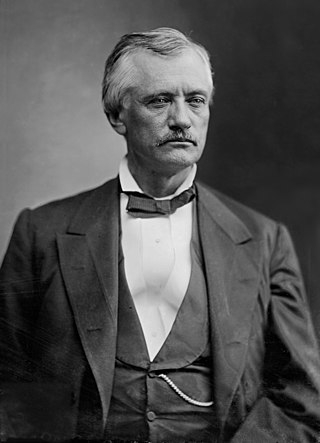

Columbus Delano was an American lawyer, rancher, banker, statesman, and a member of the prominent Delano family. Forced to live on his own at an early age, Delano struggled to become a self-made man. Delano was elected U.S. Congressman from Ohio, serving two full terms and one partial one. Prior to the American Civil War, Delano was a National Republican and then a Whig; as a Whig, he was identified with the faction of the party that opposed the spread of slavery into the Western territories. He became a Republican when the party was founded as the major anti-slavery party after the demise of the Whigs in the 1850s. During Reconstruction Delano advocated federal protection of African-Americans' civil rights, and argued that the former Confederate states should be administered by the federal government, but not as part of the United States until they met the requirements for readmission to the Union.

George Henry Williams was an American judge and politician. He served as chief justice of the Oregon Supreme Court, was the 32nd Attorney General of the United States, and was elected Oregon's U.S. senator, and served one term. Williams, as U.S. senator, authored and supported legislation that allowed the U.S. military to be deployed in Reconstruction of the southern states to allow for an orderly process of re-admittance into the United States. Williams was the first presidential Cabinet member to be appointed from the Pacific Coast. As attorney general under President Ulysses S. Grant, Williams continued the prosecutions that shut down the Ku Klux Klan. He had to contend with controversial election disputes in Reconstructed southern states. President Grant and Williams legally recognized P. B. S. Pinchback as the first African American state governor. Williams ruled that the Virginius, a gun-running ship delivering men and munitions to Cuban revolutionaries, which was captured by Spain during the Virginius Affair, did not have the right to bear the U.S. flag. However, he also argued that Spain did not have the right to execute American crew members. Nominated for Supreme Court Chief Justice by President Grant, Williams failed to be confirmed by the U.S. Senate primarily due to Williams's opposition to U.S. Attorney A. C. Gibbs, his former law partner, who refused to stop investigating Republican fraud in the special congressional election that resulted in a victory for Democrat James Nesmith.

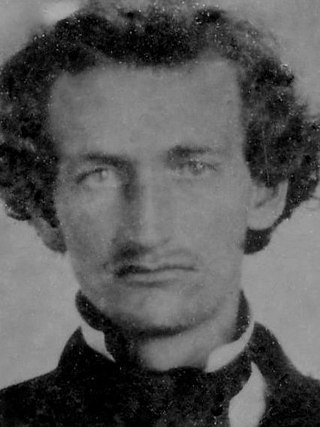

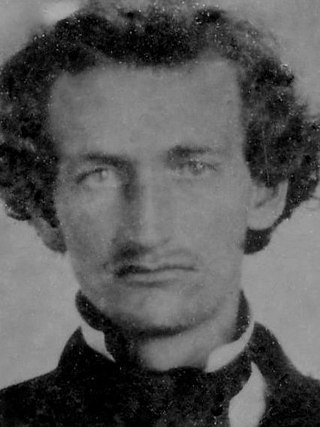

John Tyler Morgan was an American politician who was a brigadier general in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War and later was elected for six terms as the U.S. Senator (1877–1907) from the state of Alabama. A prominent slaveholder before the Civil War, he became the second Grand Dragon of the Ku Klux Klan in Alabama during the Reconstruction era. Morgan and fellow Klan member Edmund W. Pettus became the ringleaders of white supremacy in Alabama and did more than anyone else in the state to overthrow Reconstruction efforts in the wake of the Civil War. When President Ulysses S. Grant dispatched U.S. Attorney General Amos Akerman to prosecute the Klan under the Enforcement Acts, Morgan was arrested and jailed.

The Enforcement Acts were three bills that were passed by the United States Congress between 1870 and 1871. They were criminal codes that protected African Americans’ right to vote, to hold office, to serve on juries, and receive equal protection of laws. Passed under the presidency of Ulysses S. Grant, the laws also allowed the federal government to intervene when states did not act to protect these rights. The acts passed following the ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment to the US Constitution, which gave full citizenship to anyone born in the United States or freed slaves, and the Fifteenth Amendment, which banned racial discrimination in voting.

The Enforcement Act of 1871, also known as the Ku Klux Klan Act, Third Enforcement Act, Third Ku Klux Klan Act, Civil Rights Act of 1871, or Force Act of 1871, is an Act of the United States Congress that was intended to combat the paramilitary vigilantism of the Ku Klux Klan. The act made certain acts committed by private persons federal offenses including conspiring to deprive citizens of their rights to hold office, serve on juries, or enjoy the equal protection of law. The Act authorized the President to deploy federal troops to counter the Klan and to suspend the writ of habeas corpus to make arrests without charge.

James M. Hinds was the first U.S. Congressman assassinated in office. He served as member of the United States House of Representatives for Arkansas from June 24, 1868 until his assassination by the Ku Klux Klan. Hinds, who was white, was an advocate of civil rights for black former slaves during the Reconstruction era following the American Civil War.

At the end of the American Civil War, the devastation and disruption in the state of Georgia were dramatic. Wartime damage, the inability to maintain a labor force without slavery, and miserable weather had a disastrous effect on agricultural production. The state's chief cash crop, cotton, fell from a high of more than 700,000 bales in 1860 to less than 50,000 in 1865, while harvests of corn and wheat were also meager. The state government subsidized construction of numerous new railroad lines. White farmers turned to cotton as a cash crop, often using commercial fertilizers to make up for the poor soils they owned. The coastal rice plantations never recovered from the war.

The Enforcement Act of 1870, also known as the Civil Rights Act of 1870 or First Ku Klux Klan Act, or Force Act, is a United States federal law that empowers the President to enforce the first section of the Fifteenth Amendment throughout the United States. The act was the first of three Enforcement Acts passed by the United States Congress in 1870 and 1871, during the Reconstruction Era, to combat attacks on the voting rights of African Americans from state officials or violent groups like the Ku Klux Klan.

The presidency of Ulysses S. Grant began on March 4, 1869, when Ulysses S. Grant was inaugurated as the 18th president of the United States, and ended on March 4, 1877. The Reconstruction era took place during Grant's two terms of office. The Ku Klux Klan caused widespread violence throughout the South against African Americans. By 1870, all former Confederate states had been readmitted into the United States and were represented in Congress; however, Democrats and former slave owners refused to accept that freedmen were citizens who were granted suffrage by the Fifteenth Amendment, which prompted Congress to pass three Force Acts to allow the federal government to intervene when states failed to protect former slaves' rights. Following an escalation of Klan violence in the late 1860s, Grant and his attorney general, Amos T. Akerman, head of the newly created Department of Justice, began a crackdown on Klan activity in the South, starting in South Carolina, where Grant sent federal troops to capture Klan members. This led the Klan to demobilize and helped ensure fair elections in 1872.

During Ulysses S. Grant's two terms as president of the United States (1869–1877) there were several executive branch investigations, prosecutions, and reforms carried-out by President Grant, Congress, and several members of his cabinet, in the wake of several revelations of fraudulent activities within the administration. Grant's cabinet fluctuated between talented individuals or reformers and those involved with political patronage or party corruption. Some notable reforming cabinet members were persons who had outstanding abilities and made many positive contributions to the administration. These reformers resisted the Republican Party's demands for patronage to select efficient civil servants. Although Grant traditionally is known for his administration scandals, more credit has been given to him for his appointment of reformers.

Elias Hill was a Baptist minister and leader of a York County, South Carolina congregation that emigrated to Arthington, Liberia. In May 1871, during the Reconstruction era, he was among the victims in a series of attacks in York County against local blacks by members of the Ku Klux Klan. His situation received wide attention on account of his condition, as Hill had been stricken by an illness while a child which had left him crippled with his arms and legs in a withered state. He was known for preaching about rights and equality, and taught local children how to read and write.

Jim Williams was an African-American soldier and militia leader in the 1860s and 1870s in York County, South Carolina. He escaped slavery during the US Civil War and joined the Union Army. After the war, Williams led a black militia organization which sought to protect black rights in the area. In 1871, he was lynched and hung by members of the local Ku Klux Klan. As a result, a large group of local blacks immigrated to Liberia, West Africa.

James Rufus Bratton (1821–1897) was a medical doctor, army surgeon, civic leader, and leader in the Ku Klux Klan in South Carolina with whom he was guilty of committing numerous crimes. Bratton trained in medicine in Philadelphia in the 1840s but spent most of his life in Yorkville, South Carolina. He joined the Confederate Army as an assistant surgeon in April 1861, the opening month of the American Civil War. After the war, he became an opponent of Reconstruction and a leader of the Ku Klux Klan. He was one of the leaders linked in the lynching and killing of local black leader Jim Williams. This led to a string of violent attacks which eventually led to a large group of York County blacks emigrating to Liberia. Bratton fled to London, Ontario, to escape prosecution, but later was able to return to South Carolina, where he pursued his career in medicine for the remainder of his life.

The Eutaw riot was an episode of white racial violence in Eutaw, Alabama, the county seat of Greene County, on October 25, 1870, during the Reconstruction Era in the United States. It was related to an extended period of campaign violence before the fall gubernatorial election, as white Democrats in the state used racial terrorism to suppress black Republican voting. White Klan members attacked a Republican rally of 2,000 black citizens in the courthouse square, killing as many as four and wounding 54.

On October 17, 1871, U.S. President Ulysses Grant declared nine South Carolina counties to be in active rebellion, and suspended habeas corpus. The order allowed federal troops, under the command of Major Lewis Merrill, to execute mass-arrests and begin the process of crushing the South Carolina Ku Klux Klan in federal court. Merrill reported 169 arrests in York County before January 1872. Numerous Klansmen fled the state, and more were quieted by fear of prosecution. Nearly 500 men surrendered to Merrill voluntarily, gave confessions or evidence, and were released. At the Fourth Federal Circuit Court session in Columbia, South Carolina beginning November 1871, United States District Attorney David T. Corbin and South Carolina Attorney General Daniel H. Chamberlain convicted 5 Klansmen in trial court, and secured convictions based on confession from 49 others. In the next Fourth Federal Circuit Court session in Charleston, South Carolina in April 1872, Corbin convicted 86 more Klansmen. Klan activities vanished while prosecutions were ongoing and publicized, but, by the end of 1872, federal will dissolved in the face of waning Republican support for Reconstruction. At the end of 1872 some 1,188 Enforcement Act cases remained to be tried. White Northern interests began to seek a more conciliatory relationship with Southern states, and lamented Southern papers' exaggerated tales of "bayonet rule." During the summer of 1873, President Grant announced a policy of clemency for those Klansmen who had not yet been tried, and pardon for those who had. The remaining cases were not tried, and prosecutions under the Enforcement Acts were all but abandoned after 1874.