Related Research Articles

Afonso I, also called Afonso Henriques, nicknamed the Conqueror and the Founder by the Portuguese, was the first king of Portugal. He achieved the independence of the County of Portugal, establishing a new kingdom and doubling its area with the Reconquista, an objective that he pursued until his death.

A chronicle is a historical account of events arranged in chronological order, as in a timeline. Typically, equal weight is given for historically important events and local events, the purpose being the recording of events that occurred, seen from the perspective of the chronicler. A chronicle which traces world history is a universal chronicle. This is in contrast to a narrative or history, in which an author chooses events to interpret and analyze and excludes those the author does not consider important or relevant.

The Kingdom of Asturias was a kingdom in the Iberian Peninsula founded by the Visigothic nobleman Pelagius. It was the first Christian political entity established after the Umayyad conquest of Visigothic Hispania in 711. In the Summer of 722, Pelagius defeated an Umayyad army at the Battle of Covadonga, in what is retroactively regarded as the beginning of the Reconquista.

The History of the Britons is a purported history of early Britain written around 828 that survives in numerous recensions from after the 11th century. The Historia Brittonum is commonly attributed to Nennius, as some recensions have a preface written in that name. Some experts have dismissed the Nennian preface as a late forgery and argued that the work was actually an anonymous compilation.

The Annales Cambriae is the title given to a complex of Latin chronicles compiled or derived from diverse sources at St David's in Dyfed, Wales. The earliest is a 12th-century presumed copy of a mid-10th-century original; later editions were compiled in the 13th century. Despite the name, the Annales Cambriae record not only events in Wales, but also events in Ireland, Cornwall, England, Scotland and sometimes further afield, though the focus of the events recorded especially in the later two-thirds of the text is Wales.

Galician–Portuguese, also known as Old Galician–Portuguese, Old Galician or Old Portuguese, Medieval Galician or Medieval Portuguese when referring to the history of each modern language, was a West Iberian Romance language spoken in the Middle Ages, in the northwest area of the Iberian Peninsula. Alternatively, it can be considered a historical period of the Galician, Fala, and Portuguese languages.

The Lusitanians were an Indo-European-speaking people living in the far west of the Iberian Peninsula, in present-day central Portugal and Extremadura and Castilla y Leon of Spain. After its conquest by the Romans, the land was subsequently incorporated as a Roman province named after them (Lusitania).

Tui is a municipality in the province of Pontevedra, in the autonomous community of Galicia, Spain. It is located in the comarca of O Baixo Miño on the right bank of the Miño River, facing the Portuguese town of Valença. The municipality of Tui is composed of 11 parishes: Randufe, Malvas, Pexegueiro, Areas, Pazos de Reis, Rebordáns, Ribadelouro, Guillarei, Paramos, Baldráns and Caldelas.

This is a timeline of notable events during the period of Muslim presence in Iberia, starting with the Umayyad conquest in the 8th century.

Imperator totius Hispaniae is a Latin title meaning "Emperor of All Spain". In Spain in the Middle Ages, the title "emperor" was used under a variety of circumstances from the ninth century onwards, but its usage peaked, as a formal and practical title, between 1086 and 1157. It was primarily used by the kings of León and Castile, but it also found currency in the Kingdom of Navarre and was employed by the counts of Castile and at least one duke of Galicia. It signalled at various points the king's equality with the rulers of the Byzantine Empire and Holy Roman Empire, his rule by conquest or military superiority, his rule over several ethnic or religious groups, and his claim to suzerainty over the other kings of the peninsula, both Christian and Muslim. The use of the imperial title received scant recognition outside of Spain and it had become largely forgotten by the thirteenth century.

The Diocese of Coimbra is a Latin Church diocese of the Catholic Church in Coimbra, Portugal. It is a suffragan of the Archdiocese of Braga.

The Códice de Roda or Códice de Meyá is a medieval manuscript that represents a unique primary source for details of the 9th- and early 10th-century Kingdom of Navarre and neighbouring principalities. It is currently held in Madrid as Royal Academy of History MS 78.

Hispania was the Roman name for the Iberian Peninsula. Under the Roman Republic, Hispania was divided into two provinces: Hispania Citerior and Hispania Ulterior. During the Principate, Hispania Ulterior was divided into two new provinces, Baetica and Lusitania, while Hispania Citerior was renamed Hispania Tarraconensis. Subsequently, the western part of Tarraconensis was split off, initially as Hispania Nova, which was later renamed "Callaecia". From Diocletian's Tetrarchy onwards, the south of the remainder of Tarraconensis was again split off as Carthaginensis, and all of the mainland Hispanic provinces, along with the Balearic Islands and the North African province of Mauretania Tingitana, were later grouped into a civil diocese headed by a vicarius. The name Hispania was also used in the period of Visigothic rule. The modern place names of Spain and Hispaniola are both derived from Hispania.

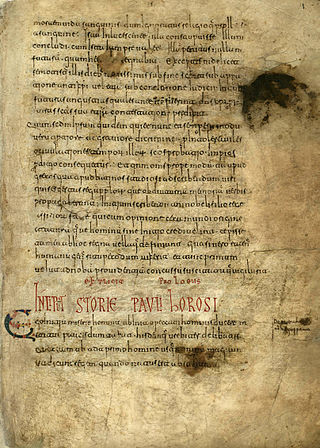

The Annales laureshamenses, also called Annals of Lorsch (AL), are a set of Reichsannalen that cover the years from 703 to 803, with a brief prologue. The annals begin where the "Chronica minora" of the Anglo-Saxon historian Bede leaves off—in the fifth year of the Emperor Tiberios III—and may have originally been composed as a continuation of Bede. The annals for the years up to 785 were written at the Abbey of Lorsch, but are dependent on earlier sources. Those for the years from 785 onward form an independent source and provide especially important coverage of the imperial coronation of Charlemagne in 800. The Annales laureshamenses have been translated into English.

Pelagiusof Oviedo was a medieval ecclesiastic, historian, and forger who served the Diocese of Oviedo as an auxiliary bishop from 1098 and as bishop from 1102 until his deposition in 1130 and again from 1142 to 1143. He was an active and independent-minded prelate, who zealously defended the privileges and prestige of his diocese. During his episcopal tenure he oversaw the most productive scriptorium in Spain, which produced the vast Corpus Pelagianum, to which Pelagius contributed his own Chronicon regum Legionensium. His work as a historian is generally reliable, but for the forged, interpolated, and otherwise skilfully altered documents that emanated from his office he has been called el Fabulador and the "prince of falsifiers". It has been suggested that a monument be built in his honour in Oviedo.

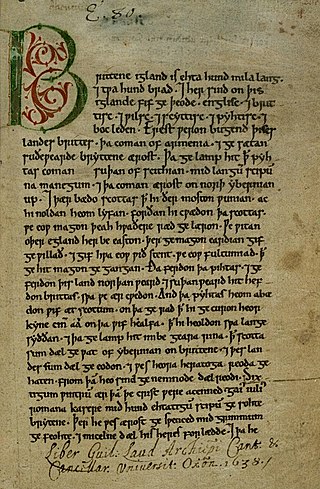

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is a collection of annals in Old English, chronicling the history of the Anglo-Saxons.

Fernando Rodríguez de Castro (1125–1185) was a Castilian nobleman, statesman and military leader who made his career in León. He was the leader of the House of Castro during the civil wars that followed the death of Sancho III of Castile and the succession of the infant Alfonso VIII. He was nicknamed el Castellano in León and el Leonés in Castile.

The County of Portugal refers to two successive medieval counties in the region around Guimarães and Porto, today corresponding to littoral northern Portugal, within which the identity of the Portuguese people formed. The first county existed from the mid-ninth to the mid-eleventh centuries as a vassalage of the Kingdom of Asturias and the Kingdom of Galicia and also part of the Kingdom of León, before being abolished as a result of rebellion. A larger entity under the same name was then reestablished in the late 11th century and subsequently elevated by its count in the mid-12th century into an independent Kingdom of Portugal.

The Chronicon Lusitanum or Lusitano is a chronicle of the history of Portugal from the earliest migrations of the Visigoths through the reign of Portugal's first king, Afonso Henriques (1139–85). The entries in the chronicle, ordered by year and dated by the Spanish Era, get increasingly longer and the majority of the text deals with the reign of Afonso. The conventional title of the chronicle means "Lusitanian chronicle" or "chronicle of the Goths". It was first given by the editor Enrique Flórez, who rejected the title under which it had previously been edited because of its subject matter. Flórez also claims that the manuscript of the Chronicon had previously been utilised by André de Resende, the first archaeologist of Portugal, and Manuel Severim de Faria, the first journalist of Portugal; it was also edited in the third volume of the Monarchia Lusitana by António Brandão (1632).

The Livro da Noa is a medieval codex that originated in the monastery of Santa Cruz de Coimbra and is now preserved in the Torre do Tombo National Arquive. The present volume results from the separate binding, in the 17th century, of the last five quires of a psalter containing the prayers of the Nones, from which it took its name. It was also known as the 'Book of the Eras' and the 'Book of the Sacristy'. It contains a collection of short texts, mostly historiographical, which were copied at different times: the earliest ones around 1200, others in the 14th century, and the latest in the 15th century.

References

- ↑ Furtado, Rodrigo (2021), "Writing history in Portugal before 1200", Journal of Medieval History 47, 145–173, p. 160.

- 1 2 David, Pierre (1947), "Annales Portugalenses Veteres", Revista Portuguesa de História, 82–128.

- ↑ Lisbon, AN-TT, CRSA-MSCC, liv. 99, ff. 10v–12v.

- ↑ Porto, BPM, SC 4/23, f. 330va.

- ↑ Madrid, Complutense, 134, ff. 2ra–b.

- ↑ Flórez, Enrique (1767), España Sagrada 23, Madrid: Antonio Marín, 315-317; Herculano, Alexandre (1856), ‘Chronicon Complutense siue Alcobacense’, Portugaliae Monumenta Historica SS 1, Olisipone: Typis academicis, 17-19.

- 1 2 Bautista, Francisco (2009), "Breve historiografía: Listas regias y anales en la Península Ibérica (siglos VII-XII)", Talia Dixit 4, 113–190.

- ↑ Lisboa, AN-TT, CRSA-MSCC, liv. 99, ff. 2r–3v.

- ↑ Lisboa, AN-TT, CSL, liv. 1, f. 1r.

- ↑ Blöcker-Walter, Monica (1966), Alfons I. von Portugal. Studien zu Geschichte und Sage des Begründers der portugiesischen Unabhängigkeiten, Zurich: Fretz und Wasmuth Verlag.

- ↑ Furtado, Rodrigo (2021). "Writing history in Portugal before 1200", Journal of Medieval History 47, 145–173, p. 164.

- ↑ Mattoso, José (1993), "Anais", en Giulia Lanciani y Giuseppe Tavani, Dicionário da Literatura Medieval Galega e Portuguesa, Lisboa: Editorial Caminho, pp. 50–51; Krus, Luís (2011). "A produção do passado nas comunidades letradas do Entre Minho e Mondego nos séculos XI e XII. As origens da analística portuguesa", en Luís Krus, A Construção do Passado Medieval. Textos Inéditos e Publicados, Lisboa: IEM, pp. 235-237, and Gouveia, Mário (2010), "O limiar da tradição no moçarabismo conimbricense: os Anais de Lorvão e a memória monástica do território de fronteira (séc. IX-XII)", Medievalista 8, pp. 23-25.

- ↑ Furtado, Rodrigo (2021), "Writing history in Portugal before 1200", Journal of Medieval History 47, 145–173, pp. 163-166.