Paranthropus is a genus of extinct hominin which contains two widely accepted species: P. robustus and P. boisei. However, the validity of Paranthropus is contested, and it is sometimes considered to be synonymous with Australopithecus. They are also referred to as the robust australopithecines. They lived between approximately 2.9 and 1.2 million years ago (mya) from the end of the Pliocene to the Middle Pleistocene.

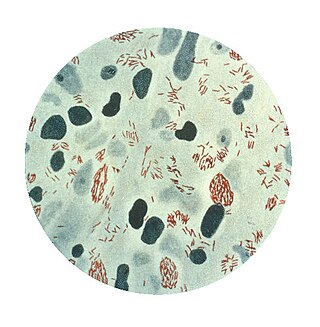

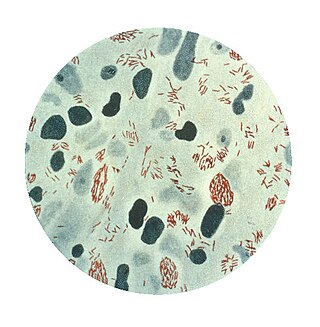

Mycobacterium is a genus of over 190 species in the phylum Actinomycetota, assigned its own family, Mycobacteriaceae. This genus includes pathogens known to cause serious diseases in mammals, including tuberculosis and leprosy in humans. The Greek prefix myco- means 'fungus', alluding to this genus' mold-like colony surfaces. Since this genus has cell walls with a waxy lipid-rich outer layer that contains high concentrations of mycolic acid, acid-fast staining is used to emphasize their resistance to acids, compared to other cell types.

Mycobacterium leprae is one of the two species of bacteria that cause Hansen’s disease (leprosy), a chronic but curable infectious disease that damages the peripheral nerves and targets the skin, eyes, nose, and muscles.

Paranthropus boisei is a species of australopithecine from the Early Pleistocene of East Africa about 2.5 to 1.15 million years ago. The holotype specimen, OH 5, was discovered by palaeoanthropologist Mary Leakey in 1959 at Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania and described by her husband Louis a month later. It was originally placed into its own genus as "Zinjanthropus boisei", but is now relegated to Paranthropus along with other robust australopithecines. However, it is also argued that Paranthropus is an invalid grouping and synonymous with Australopithecus, so the species is also often classified as Australopithecus boisei.

Paleopathology, also spelled palaeopathology, is the study of ancient diseases and injuries in organisms through the examination of fossils, mummified tissue, skeletal remains, and analysis of coprolites. Specific sources in the study of ancient human diseases may include early documents, illustrations from early books, painting and sculpture from the past. Looking at the individual roots of the word "Paleopathology" can give a basic definition of what it encompasses. "Paleo-" refers to "ancient, early, prehistoric, primitive, fossil." The suffix "-pathology" comes from the Latin pathologia meaning "study of disease." Through the analysis of the aforementioned things, information on the evolution of diseases as well as how past civilizations treated conditions are both valuable byproducts. Studies have historically focused on humans, but there is no evidence that humans are more prone to pathologies than any other animal.

Jane Ellen Buikstra is an American anthropologist and bioarchaeologist. Her 1977 article on the biological dimensions of archaeology coined and defined the field of bioarchaeology in the US as the application of biological anthropological methods to the study of archaeological problems. Throughout her career, she has authored over 20 books and 150 articles. Buikstra's current research focuses on an analysis of the Phaleron cemetery near Athens, Greece.

Francis Clark Howell, generally known as F. Clark Howell, was an American anthropologist.

Robert Spencer Corruccini is an American anthropologist, distinguished professor, Smithsonian Institution Research Fellow, Human Biology Council Fellow, and the 1994 Outstanding Scholar at Southern Illinois University-Carbondale. As a medical and dental anthropologist, Corruccini is most noted for his work on the theory of malocclusion and his extensive work in a slave cemetery at Newton Plantation in Barbados.

Robert Turner Boyd is an American anthropologist. He is professor of the School of Human Evolution and Social Change (SHESC) at Arizona State University (ASU). His research interests include evolutionary psychology and in particular the evolutionary roots of culture. Together with his primatologist wife, Joan B. Silk, he wrote the textbook How Humans Evolved.

Christy G. Turner II was an American anthropologist known for his research on dental anthropology, perimortem taphonomy, and his theories about the populating of the American continent in three migrating waves from Northeast Asia, which received support from genetic research. Turner's work spanned all the fields of Anthropology, and his fieldwork included exploring the interaction between humans and animals during the Ice Age in Siberia and taking dental casts of indigenous peoples in the Aleutian Islands.

Cercopithecoides is an extinct genus of colobine monkey from Africa which lived during the latest Miocene to the Pleistocene period. There are several recognized species, with the smallest close in size to some of the larger extant colobines, and males of the largest species weighed over 50 kilograms (110 lb).

Christina Warinner is an American anthropologist best known for her research on the evolution of ancient microbiomes. She is an Assistant Professor of Anthropology at Harvard University and the Sally Starling Seaver Assistant Professor at the Radcliffe Institute. Warinner is also a Research group leader at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Jena, Germany.

Kirsten Bos is a Canadian physical anthropologist. She is Group Leader of Molecular Palaeopathology at Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History. Her research focuses on ancient DNA and infectious diseases.

Camilla F. Speller is a biomolecular archaeologist, Assistant Professor in Anthropological Archaeology at the University of British Columbia Department of Anthropology.

Kaye Reed is a biological anthropologist focused on discovering evidence of early hominins and interpreting their paleoenvironment. She is presently concentrating her research on the lower Awash Valley in Ethiopia, as well as the South African Pleistocene, in order to study behavioral ecology.Kaye Reed is currently working at Arizona State University (ASU) in Tempe, AZ, where she is the Director of the School of Human Evolution and Social Change (SHESC). She has been a full professor since 2012 within SHESC, as well as a Research Associate within the Institute of Human Origins (IHO). Reed’s other research interests include the paleoecology of early hominids, mammalian paleontology and biogeography, community ecology, human evolution, and macroecology.

Mary W. Marzke was an American anthropologist. Her research focuses on the evolution of the hominin hand.

B. Holly Smith is an American biological anthropologist. She is currently a research professor in the Center for Advanced Study of Human Paleobiology at The George Washington University. She is also a visiting research professor at the University of Michigan Museum of Anthropological Archaeology. The majority of her work is concentrated in evolutionary biology, paleoanthropology, life history, and dental anthropology.

Joan B. Silk is an American primatologist, Regents Professor in the School of Human Evolution and Social Change (SHESC) at Arizona State University. Her research interests include evolutionary anthropology, animal behavior, and primatology. Together with her anthropologist husband, Robert T. Boyd, she wrote the textbook How Humans Evolved.

Near Eastern bioarchaeology covers the study of human skeletal remains from archaeological sites in Cyprus, Egypt, Levantine coast, Jordan, Turkey, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Kuwait, Bahrain, United Arab Emirates, Oman, and Yemen.

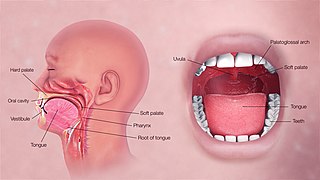

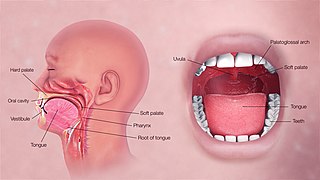

The evolution of the human oral microbiome is the study of microorganisms in the oral cavity and how they have adapted over time. There are recent advancements in ancient dental research that have given insight to the evolution of the human oral microbiome. Using these techniques it is now known what metabolite classes have been preserved and the difference in genetic diversity that exists from ancient to modern microbiota. The relationship between oral microbiota and its human host has changed and this transition can directly be linked to common diseases in human evolutionary past. Evolutionary medicine provides a framework for reevaluating oral health and disease and biological anthropology provides the context to identify the ancestral human microbiome. These disciplines together give insights into the oral microbiome and can potentially help contribute to restoring and maintaining oral health in the future.