List of notable members

| | This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (September 2024) |

Armenian National Assembly was the governing body of the Armenian millet in the Ottoman Empire, established by the Armenian National Constitution of 1863. [1]

Tax paying members of the Armenian Gregorian church were given suffrage to elect representatives to the National Assembly, which included 140 yerespokhan, or deputies, 20 of whom were from the clergy. [2] Voters were to elect 140 out of a list of 220. [3]

Constantinople was disproportionately represented in the chamber, as 80 of the lay deputies and all the clergy were elected from the capital. Therefore, despite making up 90% of the Armenian population, those in the provinces were represented by 2/7ths of the assembly. Suffrage was granted to tax paying members of the Gregorian church. Electoral law in the capital saw voters choosing candidates prepared by an electoral council in each quarter of the city. Provincial elections had three stages: voters voted for a provincial assembly which then voted for a list of candidates prepared by local councils. [2]

The National Assembly elected the patriarch and supervised his activities. [3] In addition, a religious council of 12 members, administered monasteries, donations, and hospitals. [4] It also elected a civil assembly of 20 members, which in turn appointed two councils: a judicial council, chaired by a patriarchal vicar, and a council for educational affairs. [3] Other committees are appointed in the areas of finance, expenditures and taxes, social litigation, and other financial and legal matters. [3] Armenians were required to participate in the elections of the patriarch and the community councils through their representatives, as well as to pay taxes in order to preserve and defend their rights. [4]

The National Assembly was a platform which Armenian representatives took to highlight government corruption and abuses by Kurdish tribes. In 1871 a commission of 8 members half lay and half clerical, chaired by the Archbishop of Nicomedia Nerses, researched and reported the abuses and exactions suffered by the Christian populations of Armenia, and proposed the necessary measures to put an end to the state affairs. [5] In 1913, a memorandum was dispatched to the Grand Vizier Mahmud Shevket Pasha on the difficult disposition of the Armenians in the Empire. [6]

The national assembly met into the 1910s, with its last meeting being July 4, 1914. [7]

| | This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (September 2024) |

The Armenian genocide was the systematic destruction of the Armenian people and identity in the Ottoman Empire during World War I. Spearheaded by the ruling Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), it was implemented primarily through the mass murder of around one million Armenians during death marches to the Syrian Desert and the forced Islamization of others, primarily women and children.

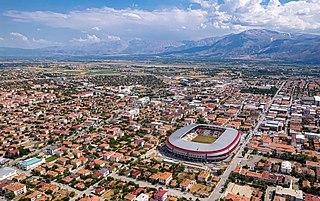

Kozan, formerly Sis, is a municipality and district of Adana Province, Turkey. Its area is 1,903 km2, and its population is 132,703 (2022). It is 68 kilometres northeast of Adana, in the northern section of the Çukurova plain. The Kilgen River, a tributary of the Ceyhan, flows through Kozan and crosses the plain south into the Mediterranean. The Taurus Mountains rise up sharply behind the town.

The Constitution of the Year VIII was a national constitution of France, adopted on 24 December 1799, which established the form of government known as the Consulate. The coup of 18 Brumaire had effectively given all power to Napoleon Bonaparte, and in the eyes of some, ended the French Revolution.

Erzincan, historically Yerznka, is the capital of Erzincan Province in eastern Turkey. Nearby cities include Erzurum, Sivas, Tunceli, Bingöl, Elazığ, Malatya, Gümüşhane, Bayburt, and Giresun. The city is majority Sunni Turkish with an Alevi Kurdish minority.

The Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople is an autonomous see of the Armenian Apostolic Church. The seat of the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople is the Surp Asdvadzadzin Patriarchal Church in the Kumkapı neighborhood of Istanbul.

The Imperial Reform Edict was a February 18, 1856 edict of the Ottoman government and part of the Tanzimat reforms. The decree from Ottoman Sultan Abdulmejid I promised equality in education, government appointments, and administration of justice to all regardless of creed. The decree is often seen as a result of the influence of France and Britain, which assisted the Ottoman Empire against the Russians during the Crimean War (1853–1856) and the Treaty of Paris (1856) which ended the war.

Ashot I was an Armenian king who oversaw the beginning of Armenia's second golden age. He was the son of Smbat VIII the Confessor and was a member of the Bagratuni dynasty.

The deportation of Armenian intellectuals is conventionally held to mark the beginning of the Armenian genocide. Leaders of the Armenian community in the Ottoman capital of Constantinople, and later other locations, were arrested and moved to two holding centers near Angora. The order to do so was given by Minister of the Interior Talaat Pasha on 24 April 1915. On that night, the first wave of 235 to 270 Armenian intellectuals of Constantinople were arrested. With the adoption of the Tehcir Law on 29 May 1915, these detainees were later relocated within the Ottoman Empire; most of them were ultimately killed. More than 80, such as Vrtanes Papazian, Aram Andonian, and Komitas, survived.

The Armenian National Constitution or Regulation of the Armenian Nation was a constitution in the Ottoman Empire for members of the Gregorian Armenian Millet. Promulgated in 1863, it defined the powers of the Armenian Patriarch, a newly formed Armenian National Assembly, and lay members. This code is still active among Armenian Church in diaspora. The Ottoman Turkish version was published in the Düstur. Other constitutions were promulgated for the Catholic Armenian and the Protestant Armenian millets.

Armenians were a significant minority in the Ottoman Empire. They belonged to either the Armenian Apostolic Church, the Armenian Catholic Church, or the Armenian Protestant Church, each church serving as the basis of a millet. They played a crucial role in Ottoman industry and commerce, and Armenian communities existed in almost every major city of the empire. The majority of the Armenian population made up a reaya, or peasant, class, in Eastern Anatolia. The Tanzimat reforms in the nineteenth century sought to manifest the doctrine of equality before the law. Despite their importance, Armenians were persecuted by the Ottoman authorities, especially from the latter half of the 19th century, culminating in the Armenian Genocide.

The Liège Revolution, sometimes known as the Happy Revolution, against the reigning prince-bishop of Liège, started on 18 August 1789 and lasted until the destruction of the Republic of Liège and re-establishment of the Prince-Bishopric of Liège by Austrian forces in 1791. The Liège Revolution was concurrent with the French Revolution and its effects were long-lasting and eventually led to the abolition of the Prince-Bishopric of Liège and its final annexation by French revolutionary forces in 1795.

Legislative elections were held in France between 29 August and 5 September 1791 and were the first national elections to the Legislature. They took place during a period of turmoil caused by the Flight and Arrest at Varennes, the Jacobin split, the Champ-de-Mars Massacre and the Pillnitz Declaration. Suffrage was limited to men paying taxes, although less than 25% of those eligible to do so voted.

Armenian genocide survivors were Armenians in the Ottoman Empire who survived the genocide of 1915. After the end of World War I, many tried to return home to the Ottoman rump state, which later became Turkey. The Turkish nationalist movement saw the return of Armenian survivors as a mortal threat to its nationalist ambitions and the interests of its supporters. The return of survivors was therefore impossible in most of Anatolia and thousands of Armenians who tried were murdered. Nearly 100,000 Armenians were massacred in Transcaucasia during the Turkish invasion of Armenia and another 100,000 fled from Cilicia during the French withdrawal. By 1923, about 295,000 Armenians ended up in the Soviet Union, mainly Soviet Armenia; an estimated 200,000 settled in the Middle East, forming a new wave of the Armenian diaspora; and about 100,000 Armenians lived in Constantinople and another 200,000 lived in the Turkish provinces, largely women and children who had been forcibly converted. Though Armenians in Constantinople faced discrimination, they were allowed to maintain their cultural identity, unlike those elsewhere in Turkey who continued to face forced Islamization and kidnapping of girls after 1923. Between 1922 and 1929, the Turkish authorities eliminated surviving Armenians from southern Turkey, expelling thousands to French-mandate Syria.

Raymond Haroutioun Kévorkian is a French Armenian historian. He is a Foreign Member of Armenian National Academy of Sciences. Kevorkian has a PhD in history (1980), and is a professor.

Rūm millet was the name of the Eastern Orthodox Christian community in the Ottoman Empire. Despite being subordinated within the Ottoman political system, the community maintained a certain internal autonomy.

Jean-Pierre Mahé is a French orientalist, philologist and historian of Caucasus, and a specialist of Armenian studies.

Claire Mouradian is a French historian of Armenian origin who specializes in the history and geopolitics of Caucasus and, more specifically, in the history of Armenia and Armenian diaspora. She explores in her works inter-ethnic relations in the Caucasus region, migration and the position of minorities.

The Armenian millet or the Armenian Gregorian Millet was the Ottoman millet of the Armenian Apostolic Church. It initially included not just Armenians in the Ottoman Empire but members of other Oriental Orthodox and Nestorian churches including the Coptic Church, Chaldean Catholic Church, Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church, Syriac Orthodox Church, and the Assyrian Church of the East, although most of these groups obtained their own millet in the nineteenth century. The Armenian Catholic and Armenian Protestants also obtained their own millets in the 1850s.

The Armenian National Delegation is a diplomatic mission and an Armenian organization whose objective is to advocate for the claims of the Armenians of Western Armenia between 1912 and 1925. The organization was established by Georges V Soureniants and initially led by the businessman and diplomat Boghos Nubar Pasha until 1921.

The Armenian delegation at the Berlin Congress was a diplomatic mission led by Archbishop Mkrtich Khrimian, whose objective was to advocate for the interests of Ottoman Armenians before the Great Powers following the Russian victory over the Ottoman Empire in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-1878. This congress marked the inception of the Armenian Question.