This article needs additional citations for verification .(June 2010) |

The crescent and star flag of the Ottoman Empire, an early 19th-century design officially adopted in 1844 | |

| Use | National flag and ensign |

|---|---|

| Proportion | 2:3 |

| Adopted | 1844 |

| Relinquished | 1923 (Proclamation of the Republic of Turkey) |

| Design | A red field charged with a white crescent and star slightly left-of-center. [1] |

The Ottoman Empire used various flags and naval ensigns during its history. The crescent and star came into use in the second half of the 18th century. A buyruldu (decree) from 1793 required that the ships of the Ottoman Navy were to use a red flag with the star and crescent in white. In 1844, a version of this flag, with a five-pointed star, was officially adopted as the Ottoman national flag. The decision to adopt a national flag was part of the Tanzimat reforms which aimed to modernize the Ottoman state in line with the laws and norms of contemporary European states and institutions.

Contents

- Early flag

- Crescent flag

- Naval standards

- Crescent and star flag

- Source of the Star and Crescent symbol

- Imperial standards

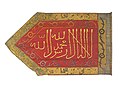

- Army Flags and Standards with Shahada

- See also

- References

- External links

The star and crescent design later became a common element in the national flags of Ottoman successor states in the 20th century. The current flag of Turkey is essentially the same as the late Ottoman flag, but has more specific legal standardizations (regarding its measures, geometric proportions, and exact tone of red) that were introduced with the Turkish Flag Law on 29 May 1936. Before the legal standardization, the star and crescent could have slightly varying slimness or positioning depending on the rendition.