Related Research Articles

The Young Turks was a broad opposition movement in the late Ottoman Empire agitating against Sultan Abdul Hamid II's absolutist regime. The most powerful organization of the movement, and the most conflated, was the Committee of Union and Progress, though its goals, strategies, and membership continuously morphed throughout Abdul Hamid's reign. By the 1890s, the Young Turks were mainly a loose and contentious network of intelligentsia exiled in Western Europe and Egypt that made a living by selling their newspapers to secret subscribers.

Drastamat Kanayan, better known as Dro (Դրո), was an Armenian military commander and politician. He was a member of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation. He briefly served as Defence Minister of the First Republic of Armenia in 1920, during the country's brief independence. During World War II, he led the Armenian Legion, which consisted of Armenian POWs who opted to fight for Nazi Germany rather than face the brutal conditions of the Nazis' camps.

The Treaty of Adrianople concluded the Russo-Turkish War of 1828–29, between Imperial Russia and the Ottoman Empire. The terms favored Russia, which gained access to the mouths of the Danube and new territory on the Black Sea. The treaty opened the Dardanelles to all commercial vessels, granted autonomy to Serbia, and promised autonomy for Greece. It also allowed Russia to occupy Moldavia and Walachia until the Ottoman Empire had paid a large indemnity; those indemnities were later reduced. The treaty was signed on 14 September 1829 in Adrianople by Count Alexey Fyodorovich Orlov of Russia and Abdülkadir Bey of the Ottoman Empire.

The dissolution of the Ottoman Empire (1908–1922) was a period of history of the Ottoman Empire beginning with the Young Turk Revolution and ultimately ending with the empire's dissolution and the founding of the modern state of Turkey.

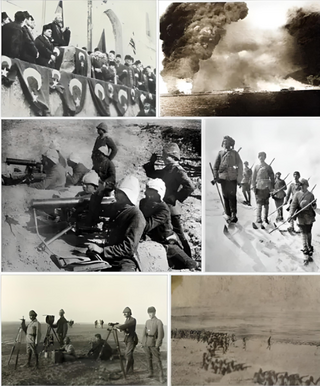

The Middle Eastern theatre of World War I saw action between 30 October 1914 and 30 October 1918. The combatants were, on one side, the Ottoman Empire, with some assistance from the other Central Powers; and on the other side, the British as well as troops from the British Dominions of Australia, Canada, and New Zealand, the Russians, and the French from among the Allied Powers. There were five main campaigns: the Sinai and Palestine, Mesopotamian, Caucasus, Persian, and Gallipoli campaigns.

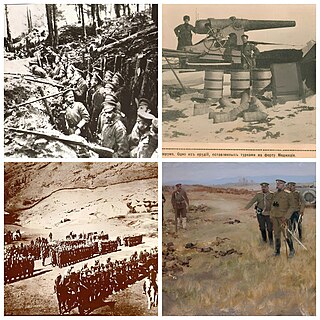

The Caucasus campaign comprised armed conflicts between the Russian Empire and the Ottoman Empire, later including Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, the Mountainous Republic of the Northern Caucasus, the German Empire, the Central Caspian Dictatorship, and the British Empire, as part of the Middle Eastern theatre during World War I. The Caucasus campaign extended from the South Caucasus to the Armenian Highlands region, reaching as far as Trabzon, Bitlis, Mush and Van. The land warfare was accompanied by naval engagements in the Black Sea.

Russo-Turkish wars or Russo-Ottoman wars were a series of twelve wars fought between the Russian Empire and the Ottoman Empire between the 16th and 20th centuries. It was one of the longest series of military conflicts in European history. Except for the war of 1710–11, as well as the Crimean War which is often treated as a separate event, the conflicts ended disastrously for the Ottoman Empire, which was undergoing a long period of stagnation and decline; conversely, they showcased the ascendancy of Russia as a European power after the modernization efforts of Peter the Great in the early 18th century.

Russian Armenia is the period of Armenian history under Russian rule from 1828, when Eastern Armenia became part of the Russian Empire following Qajar Iran's loss in the Russo-Persian War (1826–1828) and the subsequent ceding of its territories that included Eastern Armenia per the out coming Treaty of Turkmenchay of 1828.

The defense of Van was the armed resistance of the Armenian population of Van against the Ottoman Empire's attempts to massacre the Ottoman Armenian population of the Van Vilayet in the 1915 Armenian genocide. Several contemporaneous observers and later historians have concluded that the Ottoman government deliberately instigated an armed Armenian resistance in the city and then used this insurgency as the main pretext to justify beginning the deportation and slaughter of Armenians throughout the empire. Witness reports agree that the Armenian posture at Van was defensive and an act of resistance to massacre. The self-defense action is frequently cited in Armenian genocide denial literature; it has become "the alpha and omega of the plea of 'military necessity'" to excuse the genocide and portray the persecution of Armenians as justified.

The Armenian volunteer units were units composed of Armenians within the Imperial Russian Army during World War I. Composed of several groups at battalion strength, its ranks were primarily made up of Armenians from the Russian Empire, though there were also a number of Armenians from the Ottoman Empire. The Russian-Armenian volunteer units took part in military activities in the Middle Eastern theater of World War I.

The occupation of Western Armenia by the Russian Empire during World War I began in 1915 and was formally ended by the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. It was sometimes referred to as the Republic of Van by Armenians. Aram Manukian of Armenian Revolutionary Federation was the de facto head until July 1915. It was briefly referred to as "Free Vaspurakan". After a setback beginning in August 1915, it was re-established in June 1916. The region was allocated to Russia by the Allies in April 1916 under the Sazonov–Paléologue Agreement.

The Armenian national awakening resembles that of other non-Turkish ethnic groups during the rise of nationalism under the Ottoman Empire in development of ideas of nationalism, salvation and independence in Armenia, as the Ottoman Empire tried to cover the social needs by creating the Tanzimat era, the development of Ottomanism and First Constitutional Era. However, the coexistence of the communities under Ottomanism proved to be a dysfunctional solution as did the Second Constitutional Era which also ignited the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire.

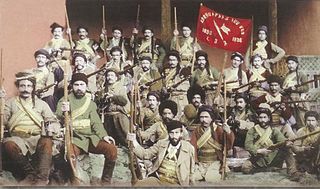

Fedayi, also known as the Armenian irregular units or Armenian militia, were Armenian civilians who voluntarily left their families to form self-defense units and irregular armed bands in reaction to the mass murder of Armenians and the pillage of Armenian villages by criminals, Turkish and Kurdish gangs, Ottoman forces, and Hamidian guards during the reign of Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid II in late 19th and early 20th centuries, known as the Hamidian massacres. Their ultimate goal was always to gain Armenian autonomy (Armenakans) or independence depending on their ideology and the degree of oppression visited on Armenians.

The partition of the Ottoman Empire was a geopolitical event that occurred after World War I and the occupation of Constantinople by British, French, and Italian troops in November 1918. The partitioning was planned in several agreements made by the Allied Powers early in the course of World War I, notably the Sykes–Picot Agreement, after the Ottoman Empire had joined Germany to form the Ottoman–German Alliance. The huge conglomeration of territories and peoples that formerly comprised the Ottoman Empire was divided into several new states. The Ottoman Empire had been the leading Islamic state in geopolitical, cultural and ideological terms. The partitioning of the Ottoman Empire after the war led to the domination of the Middle East by Western powers such as Britain and France, and saw the creation of the modern Arab world and the Republic of Turkey. Resistance to the influence of these powers came from the Turkish National Movement but did not become widespread in the other post-Ottoman states until the period of rapid decolonization after World War II.

The Armenian national movement included social, cultural, but primarily political and military movements that reached their height during World War I and the following years, initially seeking improved status for Armenians in the Ottoman and Russian Empires but eventually attempting to achieve an Armenian state.

The Battle of Baku took place in August and September 1918 between the Ottoman–Azerbaijani coalition forces led by Nuri Pasha and Bolshevik–ARF Baku Soviet forces, later succeeded by the British–Armenian–White Russian forces led by Lionel Dunsterville and saw Soviet Russia briefly re-enter the war. The battle took place during World War I, was a conclusive part of the Caucasus Campaign, but a beginning of the Armenian–Azerbaijani War.

The Armenian question was the debate following the Congress of Berlin in 1878 as to how the Armenians in the Ottoman Empire should be treated. The term became commonplace among diplomatic circles and in the popular press. In specific terms, the Armenian question refers to the protection and the freedoms of Armenians from their neighboring communities. The Armenian question explains the 40 years of Armenian–Ottoman history in the context of English, German, and Russian politics between 1877 and 1914. In 1915, the leadership of the Committee of Union and Progress, which controlled the Ottoman government, decided to end the Armenian question permanently by killing and expelling most Armenians from the empire, in the Armenian genocide.

The country of Georgia became part of the Russian Empire in the 19th century. Throughout the early modern period, the Muslim Ottoman and Persian empires had fought over various fragmented Georgian kingdoms and principalities; by the 18th century, Russia emerged as the new imperial power in the region. Since Russia was an Orthodox Christian state like Georgia, the Georgians increasingly sought Russian help. In 1783, Heraclius II of the eastern Georgian kingdom of Kartli-Kakheti forged an alliance with the Russian Empire, whereby the kingdom became a Russian protectorate and abjured any dependence on its suzerain Persia. The Russo-Georgian alliance, however, backfired as Russia was unwilling to fulfill the terms of the treaty, proceeding to annex the troubled kingdom in 1801, and reducing it to the status of a Russian region. In 1810, the western Georgian kingdom of Imereti was annexed as well. Russian rule over Georgia was eventually acknowledged in various peace treaties with Persia and the Ottomans, and the remaining Georgian territories were absorbed by the Russian Empire in a piecemeal fashion in the course of the 19th century.

The Armenian reforms, also known as the Yeniköy accord, was a reform plan devised by the European powers between 1912 and 1914 that envisaged the creation of two provinces in Ottoman Armenia placed under the supervision of two European inspectors general, who would be appointed to oversee matters related to the Armenian issues. The inspectors general would hold the highest position in the six eastern vilayets (provinces), where the bulk of the Armenian population lived, and would reside at their respective posts in Erzurum and Van. The reform package was signed into law on February 8, 1914, though it was ultimately abolished on December 16, 1914, several weeks after Ottoman entry into World War I.

Differing views of what caused the Armenian genocide include explanations focusing on nationalism, religion, and wartime radicalization and continue to be debated among scholars. In the twenty-first century, focus has shifted to multicausal explanations. Most historians agree that the genocide was not premeditated before World War I, but the role of contingency, ideology, and long-term structural factors in causing the genocide continues to be discussed.

References

- ↑ Taner Akcam, A Shameful Act, page 136

- ↑ Richard G. Hovannisian, The Armenian People from Ancient to Modern Times, 244

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 The Encyclopedia Americana, 1920, v.28, p.412

- 1 2 3 Joseph L. Grabill, (1971) Protestant Diplomacy and the Near East: Missionary Influence on American Policy, 1810-1927, page 59, ISBN 978-0-8166-0575-0

- ↑ G. Pasdermadjian (Armen Garo), Why Armenia Should be Free: Armenia's Role in the Present War, Boston, Hairenik Pub. Co, 1918, p. 20

- ↑

- Pasdermadjian, Garegin; Torossian, Aram (1918). Why Armenia Should be Free: Armenia's Role in the Present War. Hairenik Pub. Co. pp. 45.

page 17 "The CUP delegates, in order to persuade the Armenians to accept this proposal, informed them also that they had already won the co-operation of the Georgians and the Tartars, as well as the mountaineers of the northern Caucasus, and therefore the non-compliance of the Armenians under such circumstances would be very stupid and fraught with danger for them on both sides of the boundary between Turkey and Russia. In spite of these promises and threats, the executive committee of the Dashnaktzoutiun (Federation) informed the Turks that the Armenians could not accept the Turkish proposal, and on their behalf advised the Turks not to participate in the present war, which would be very disastrous to the Turks themselves."

- Pasdermadjian, Garegin; Torossian, Aram (1918). Why Armenia Should be Free: Armenia's Role in the Present War. Hairenik Pub. Co. pp. 45.

- ↑ Martin Gilbert, 2004, "The First World War," Macmillan p.108

- ↑ Avetoon Pesak Hacobian, 1917, Armenia and the War, p.78