Deir ez-Zor is the largest city in eastern Syria and the seventh largest in the country. Located on the banks of the Euphrates River 450 km (280 mi) to the northeast of the capital Damascus, Deir ez-Zor is the capital of the Deir ez-Zor Governorate. In the 2018 census, it had a population of 271,800.

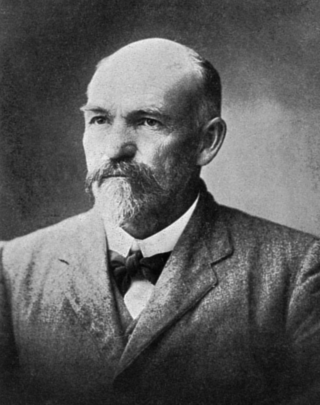

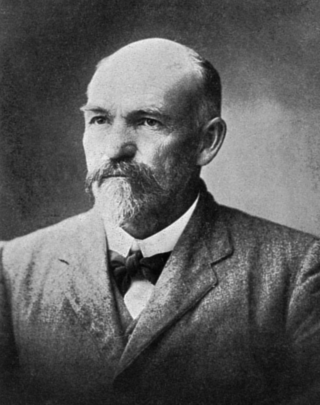

Aram Andonian was an Armenian journalist, historian and writer.

The deportation of Armenian intellectuals is conventionally held to mark the beginning of the Armenian genocide. Leaders of the Armenian community in the Ottoman capital of Constantinople, and later other locations, were arrested and moved to two holding centers near Angora. The order to do so was given by Minister of the Interior Talaat Pasha on 24 April 1915. On that night, the first wave of 235 to 270 Armenian intellectuals of Constantinople were arrested. With the adoption of the Tehcir Law on 29 May 1915, these detainees were later relocated within the Ottoman Empire; most of them were ultimately killed. More than 80, such as Vrtanes Papazian, Aram Andonian, and Komitas, survived.

Kessab, also spelled Kesab or Kasab, is a town in northwestern Syria, administratively part of the Latakia Governorate, located 59 kilometers north of Latakia. It is situated near the border with Turkey on the slope of Mount Aqraa, 800 meters above sea level. According to the Syria Central Bureau of Statistics, Kessab had a population of 1,754 in the 2004 census. Along with the surrounding villages, the sub-district of Kessab has a total population of around 2,500. Kessab has a dominant Armenian population, which dates back to the medieval ages.

The Armenians in Syria are Syrian citizens of either full or partial Armenian descent.

Al-Baggara or Bakara is an Arab tribe of the Euphrates tribes spread widely between Syria, Jordan, Iraq and Lebanon. The tribe was named by the name of their grandfather, Imam Muhammad al-Baqir, one of the grandsons of Ali ibn Abi Talib.

Karen Vel Jeppe was a Danish missionary and social worker, known for her work with Ottoman Armenian refugees and survivors of the Armenian genocide, mainly widows and orphans, from 1903 until her death in Syria in 1935. She was a member of Johannes Lepsius' Deutsche Orient-Mission and assumed responsibility for the Armenian children in the Millet Khan German Refugee Orphanage after the 1895 Urfa massacres.

Armenian Genocide Martyrs' Memorial in Deir ez-Zor, Syria, was a complex dedicated to victims of the Armenian genocide. The construction of the Martyrs' Memorial started in December 1989 and was completed in November 1990. It was consecrated on 4 May 1991 by Catholicos Karekin II of the Armenian Catholicosate of Cilicia. The memorial complex served as church, museum, monument, archive centre and exhibition. It was under the direct administration of the Armenian Prelacy, Diocese of Aleppo. Every year, on 24 April, tens of thousands of Armenian pilgrims from all over the world visited the Deir ez-Zor complex to commemorate the genocide victims, with the presence of their religious leaders.

The Vilayet of Aleppo was a first-level administrative division (vilayet) of the Ottoman Empire, centered on the city of Aleppo.

Armenian–Syrian relations are foreign relations between Armenia and Syria. Armenia has an embassy in Damascus and a consulate general in Aleppo. In 1997, Syria opened an embassy in Yerevan. Syrian Foreign Minister Farouk al-Sharaa visited Armenia in March 1992.

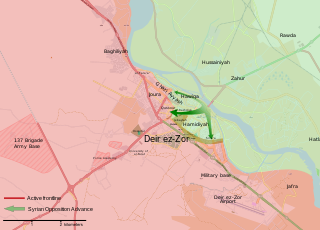

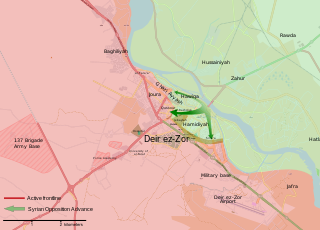

Protests against the Syrian government and violence had been ongoing in the Syrian city of Deir ez-Zor since March 2011, as part of the wider Syrian Civil War, but large-scale clashes started following a military operation in late July 2011 to secure the city of Deir ez-Zor. The rebels took over most of the province by late 2013, leaving only small pockets of government control around the city of Deir ez-Zor.

Ra's al-'Ayn camps were desert death camps near the city of Ras al-Ayn, where many Armenians were deported and slaughtered during the Armenian genocide. The site became "synonymous with Armenian suffering".

Fred Douglas Shepard was an American physician who witnessed the Armenian Genocide. Due to his relief efforts, Shepard is known to have saved many lives during the genocide. He was especially known for trying to dissuade Turkish politicians from deporting the Armenians.

Armenian Prelacy of Aleppo, is one of the oldest dioceses of the Armenian Apostolic Church outside the historic Armenian territories, covering the Syrian city of Aleppo and the governorates of Deir ez-Zor, Idlib, Latakia and Raqqa. It is known as Beroea, being named after one of the ancient names of Aleppo; when the city was renamed Beroea (Βέροια) in 301 BC by Seleucus Nicator until the Arab conquest of Syria and Aleppo in 637 AD. The seat of the bishop is the Forty Martyrs Cathedral of Aleppo. It is under the jurisdiction of the Holy See of Cilicia of the Armenian Church.

The Deir ez-Zor Governorate campaign of the Syrian civil war consists of several battles and offensives fought across the governorate of Syria:

Haj Fadel Government was a government formed during the Occupation of Zor in the eastern region of Syria and based in Deir al-Zour`s city after the departure of the Ottomans in 1918, headed by Haj Fadel Al-Aboud and it was called his name.

Ayyash Al-Haj Hussein Al-Jassim was a Syrian revolutionary who led the armed struggle against the French in Deir al-Zour Governorate in 1925 during the Great Syrian Revolt. He was sent into exile to Jableh in western Syria with his family after they were convicted of planning and carrying out future rebellions against the French. They also sentenced his eldest son Mohammed to 20 years in prison on the island of Arwad, and executed his son Mahmoud by shooting with several other revolutionaries.

The following is a timeline of the Syrian civil war for 2021. Information about aggregated casualty counts is found at Casualties of the Syrian civil war.

The following is a timeline of the Syrian civil war for 2022. Information about aggregated casualty counts is found in Casualties of the Syrian civil war.