Pavia is a town and comune of south-western Lombardy, in Northern Italy, 35 kilometres south of Milan on the lower Ticino near its confluence with the Po. It has a population of c. 73,086.

Perctarit was the first Catholic king of the Lombards who lead a religiously divided kingdom during the 7th Century. He ruled from 661 to 662 the first time and later from 671 to 688. He is significant for making Catholicism the official religion, sparing the life of an invading leader, and building projects around the capital.

Cunipert was king of the Lombards from 688 to 700. He succeeded his father Perctarit, though he was associated with the throne from 680.

The Bavarian dynasty was those kings of the Lombards who were descended from Garibald I, the Agilolfing duke of Bavaria. They came to rule the Lombards through Garibald's daughter Theodelinda, who married the Lombard king Authari in 588. The Bavarians were really a branch of the Agilolfings, and were themselves two branches: the branch descended in the female line through Garibald's eldest child and daughter, Theodelinda, and the branch descended from Garibald's eldest son Gundoald. Of the first branch, only Adaloald, Theodelinda's son by her second husband, whom she had chosen to be king, Agilulf, reigned, though her son-in-law Arioald also ruled. Through Gundoald, six kings reigned in succession, broken only by the usurper Grimuald, who married Gundoald's granddaughter:

The Certosa di Pavia is a monastery complex in Lombardy, Northern Italy, situated near a small village of the same name in the Province of Pavia, 8 km (5.0 mi) north of Pavia. Built from 1396 to 1495, it was once located at the end of the Visconti Park a large hunting park and pleasure ground belonging to the Visconti dukes of Milan, of which today only scattered parts remain. It is one of the largest monasteries in Italy.

San Pietro in Ciel d'Oro is a Catholic basilica of the Augustinians in Pavia, Italy, in the Lombardy region. Its name refers to the mosaics of gold leaf behind glass tesserae that decorate the ceiling of the apse. The plain exterior is of brick, with sandstone quoins and window framing. The paving of the church floor is now lower than the modern street level of Piazza San Pietro in Ciel d'Oro, which lies before its façade.

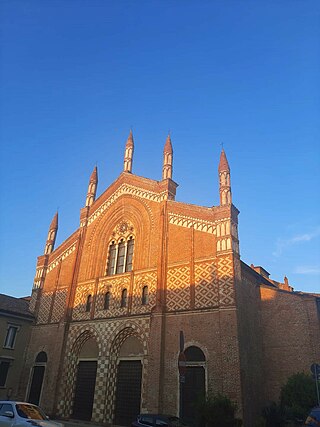

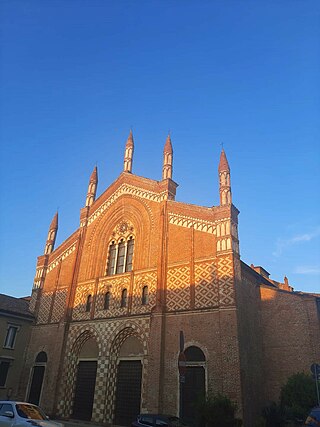

Santa Maria del Carmine is a church in Pavia, Lombardy, northern Italy, considered amongst the best examples of Lombard Gothic architecture. It was begun in 1374 by Gian Galeazzo Visconti, Duke of Milan, on a project attributed to Bernardo da Venezia. The construction followed a slow pace, and was restarted in 1432, being finished in 1461.

The Civic Museums of Pavia are a number of museums in Pavia, Lombardy, northern Italy. They are housed in the Castello Visconteo, or Visconti Castle, built in 1360 by Galeazzo II Visconti, soon after taking the city, a free city-state until then. The credited architect is Bartolino da Novara. The castle used to be the main residence of the Visconti family, while the political capital of the state was Milan. North of the castle a wide park was enclosed, also including the Certosa of Pavia, founded 1396 according to a vow of Gian Galeazzo Visconti, meant to be a sort of private chapel of the Visconti dynasty. The Battle of Pavia (1525), climax of the Italian Wars, took place inside the castle park.

San Teodoro is a Romanesque-style Roman Catholic church in the town center of Pavia, Italy.

San Lanfranco is a Romanesque-style Catholic church and former abbey, located on via San Lanfranco Vescovo, 4/6, just west of the town center of Pavia, region of Lombardy, Italy.

The church of San Francesco of Assisi is a Catholic religious building in Pavia, Lombardy, Italy.

The church of Sant'Eusebio was a church of Pavia, of which today only the crypt remains. The church was probably built by the Lombard king Rothari (636-652) as the city's Arian cathedral. It later became the fulcrum of the conversion to Catholicism of the Lombards initiated by Theodolinda and the monks of San Colombano and which later received, precisely in Pavia, a great impulse from King Aripert I (653-661) and from Bishop Anastasius.

The church of San Giovanni Domnarum is one of the oldest in Pavia. In the crypt, which was rediscovered after centuries in 1914, remains of frescoes are visible.

The Monastery of San Felice was one of the main female Benedictine monasteries of Pavia. Founded during the Lombard period, it was suppressed in the 18th century. Part of the church and the crypt survive from the original Lombard complex.

The church of San Marino is a Roman Catholic church located on Via Siro Comi in Pavia, region of Lombardy, Italy

The Church of San Tommaso is a former Catholic church and monastery in the city of Pavia, Lombardy, Italy. It is located within the historic city center and belongs to the University of Pavia.

The monastery of Santa Maria Teodote, also known as Santa Maria della Pusterla, was one of the oldest and most important female monasteries in Pavia, Lombardy, now Italy. Founded in the seventh century, it stood in the place where the diocesan seminary is located and was suppressed in the eighteenth century.

The Church of San Lazzaro is located on the eastern suburbs of Pavia. Built in the 12th century along the Via Francigena, it was equipped with a hospital dedicated to the care of pilgrims and lepers.

The Church of Santi Gervasio e Protasio is a church in Pavia, in Lombardy.

The Church of San Pietro in Verzolo is located on the eastern outskirts of Pavia, Italy, along the Via Francigena.