Bagram is a town and seat in Bagram District in Parwan Province of Afghanistan, about 60 kilometers north of the capital Kabul. It is the site of an ancient city located at the junction of the Ghorband and Panjshir Valley, near today's city of Charikar, Afghanistan. The location of this historical town made it a key passage from Ancient India along the Silk Road, leading westwards through the mountains towards Bamiyan, and north over the Kushan Pass to the Baghlan Valley and past the Kushan archeological site at Surkh Kotal, to the commercial centre of Balkh and the rest of northern Afghanistan. Bagram was also a capital of Kushan empire

The Kharoṣṭhī script, also spelled Kharoshthi, was an ancient Indo-Iranian script used by various Aryan peoples in north-western regions of the Indian subcontinent, more precisely around present-day northern Pakistan and eastern Afghanistan. It was used in Central Asia as well. An abugida, it was introduced at least by the middle of the 3rd century BCE, possibly during the 4th century BCE, and remained in use until it died out in its homeland around the 3rd century CE.

The National Museum of Afghanistan, also known as the Kabul Museum, is a two-story building located 9 km southwest of the center of Kabul in Afghanistan. As of 2014, the museum is under major expansion according to international standards, with a larger size adjoining garden for visitors to relax and walk around. The museum was once considered to be one of the world's finest.

Alexandria in the Caucasus was a colony of Alexander the Great. He founded the colony at an important junction of communications in the southern foothills of the Hindu Kush mountains, in the country of the Paropamisadae.

Scrimshaw is scrollwork, engravings, and carvings done in bone or ivory. Typically it refers to the artwork created by whalers, engraved on the byproducts of whales, such as bones or cartilage. It is most commonly made out of the bones and teeth of sperm whales, the baleen of other whales, and the tusks of walruses.

Zeionises was an Indo-Scythian satrap.

Buddhism, an Indian religion founded by Gautama Buddha, first arrived in modern-day Afghanistan through the conquests of Ashoka, the third emperor of the Maurya Empire. Among the earliest notable sites of Buddhist influence in the country is a bilingual mountainside inscription in Greek and Aramaic that dates back to 260 BCE and was found on the rocky outcrop of Chil Zena near Kandahar.

Ivory carving is the carving of ivory, that is to say animal tooth or tusk, generally by using sharp cutting tools, either mechanically or manually. Objects carved in ivory are often called "ivories".

The Hoxne Hoard is the largest hoard of late Roman silver and gold discovered in Britain, and the largest collection of gold and silver coins of the fourth and fifth centuries found anywhere within the former Roman Empire. It was found by Eric Lawes, a metal detectorist in the village of Hoxne in Suffolk, England in 1992. The hoard consists of 14,865 Roman gold, silver, and bronze coins and approximately 200 items of silver tableware and gold jewellery. The objects are now in the British Museum in London, where the most important pieces and a selection of the rest are on permanent display. In 1993, the Treasure Valuation Committee valued the hoard at £1.75 million.

Tillya tepe, Tillia tepe or Tillā tapa is an archaeological site in the northern Afghanistan province of Jowzjan near Sheberghan, excavated in 1978 by a Soviet-Afghan team led by the Soviet archaeologist Viktor Sarianidi. The hoard found there is often known as the Bactrian gold.

Inlay covers a range of techniques in sculpture and the decorative arts for inserting pieces of contrasting, often colored materials into depressions in a base object to form ornament or pictures that normally are flush with the matrix. A great range of materials have been used both for the base or matrix and for the inlays inserted into it. Inlay is commonly used in the production of decorative furniture, where pieces of colored wood, precious metals or even diamonds are inserted into the surface of the carcass using various matrices including clear coats and varnishes. Lutherie inlays are frequently used as decoration and marking on musical instruments, particularly the smaller strings.

Ahan Posh or Ahan Posh Tape is an ancient Buddhist stupa and monastery complex in the vicinity of Jalalabad, Afghanistan, dated to circa 150-160 CE, at the time of the Kushan Empire.

The Nimrud ivories are a large group of small carved ivory plaques and figures dating from the 9th to the 7th centuries BC that were excavated from the Assyrian city of Nimrud during the 19th and 20th centuries. The ivories mostly originated outside Mesopotamia and are thought to have been made in the Levant and Egypt, and have frequently been attributed to the Phoenicians due to a number of the ivories containing Phoenician inscriptions. They are foundational artefacts in the study of Phoenician art, together with the Phoenician metal bowls, which were discovered at the same time but identified as Phoenician a few years earlier. However, both the bowls and the ivories pose a significant challenge as no examples of either – or any other artefacts with equivalent features – have been found in Phoenicia or other major colonies.

Afghan art has spanned many centuries. In contrast to its independence and isolation in recent centuries, ancient and medieval Afghanistan spent long periods as part of large empires, which mostly also included parts of modern Pakistan and north India, as well as Iran. Afghan cities were often sometimes among the capitals or main cities of these, as with the Kushan Empire, and later the Mughal Empire. In addition some routes of the Silk Road to and from China pass through Afghanistan, bringing influences from both the east and west.

The Pompeii Lakshmi is an ivory statuette that was discovered in the ruins of Pompeii, a Roman city destroyed in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius 79 CE. It was found by Amedeo Maiuri, an Italian scholar, in 1938. The statuette has been dated to the first-century CE. The statuette is thought of as representing an Indian goddess of feminine beauty and fertility. It is possible that the sculpture originally formed the handle of a mirror. The yakshi is evidence of commercial trade between India and Rome in the first century CE.

The Kabul hoard, also called the Chaman Hazouri, Chaman Hazouri or Tchamani-i Hazouri hoard, is a coin hoard discovered in the vicinity of Kabul, Afghanistan in 1933. The collection contained numerous Achaemenid coins as well as many Greek coins from the 5th and 4th centuries BCE. Approximately one thousand coins were counted in the hoard. The deposit of the hoard is dated to approximately 380 BCE, as this is the probable date of the least ancient datable coin found in the hoard.

The ninety-three game pieces of the Lewis chessmen hoard were found on the Isle of Lewis in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland. Medieval in origin, they were first exhibited in Edinburgh in 1831 but it is unclear how much earlier they had been discovered. The hoard comprised seventy-eight distinctive chess pieces and fifteen other non-chess pieces, nearly all carved from walrus tusk ivory, and they are now displayed at the British Museum in London and National Museums Scotland in Edinburgh. Another chess piece, which turned up in 1964 and in 2019 was attributed to have come from the original hoard, now belongs to an undisclosed owner.

Kalliope was an Indo-Greek queen and wife of Hermaeus, who was a Western Indo-Greek king of the Eucratid Dynasty. He ruled the territory of Paropamisade in the Hindu-Kush region, with his capital in Alexandria of the Caucasus. Their reign dates from the first quarter of the first century BC.

Tepe Maranjan was a Buddhist monastery, located on the eastern outskirst of Kabul, and dated to the 4th century CE, or the 6-7th century for the Buddhist phase. Many Buddhist sculptures were discovered on the site. They are made of clay, and stylistically derived from the sculptures of Hadda, but preceded the style of the Fondukistan monastery. Tepe Maranjan can be considered as representative of the Art of Gandhara of the 5th or 6th century CE.

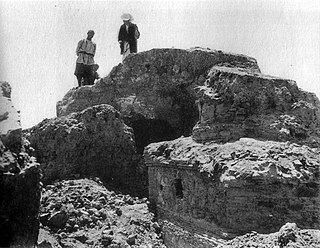

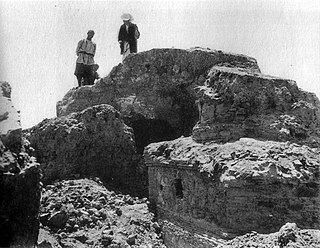

The Treasure of Begram or Begram Hoard is a group of artifacts from the 1st-2nd century CE discovered in the area of Begram, Afghanistan. The French Archaeological Delegation in Afghanistan (DAFA) conducted excavations at the site between 1936 and 1940, uncovering two walled-up strongrooms, Room 10 and Room 13. Inside, a large number of bronze, alabaster, glass, coins, and ivory objects, along with remains of furniture and Chinese lacquer bowls, were unearthed. Some of the furniture was arranged along walls, other pieces stacked or facing each other. In particular, a high percentage of the few survivals of Greco-Roman enamelled glass come from this discovery.