Venus is a Roman goddess, whose functions encompass love, beauty, desire, sex, fertility, prosperity, and victory. In Roman mythology, she was the ancestor of the Roman people through her son, Aeneas, who survived the fall of Troy and fled to Italy. Julius Caesar claimed her as his ancestor. Venus was central to many religious festivals, and was revered in Roman religion under numerous cult titles.

Lakshmi also known as Shri, is one of the principal goddesses in Hinduism. She is the goddess of wealth, fortune, power, beauty, fertility and prosperity, and associated with Maya ("Illusion"). Along with Parvati and Saraswati, she forms the Tridevi of Hindu goddesses.

In ancient Roman religion, Roma was a female deity who personified the city of Rome and, more broadly, the Roman state. She was created and promoted to represent and propagate certain of Rome's ideas about itself, and to justify its rule. She was portrayed on coins, sculptures, architectural designs, and at official games and festivals. Images of Roma had elements in common with other goddesses, such as Rome's Minerva, her Greek equivalent Athena and various manifestations of Greek Tyche, who protected Greek city-states; among these, Roma stands dominant, over piled weapons that represent her conquests, and promising protection to the obedient. Her "Amazonian" iconography shows her "manly virtue" (virtus) as fierce mother of a warrior race, augmenting rather than replacing local goddesses. On some coinage of the Roman Imperial era, she is shown as a serene advisor, partner and protector of ruling emperors. In Rome, the Emperor Hadrian built and dedicated a gigantic temple to her as Roma Aeterna, and to Venus Felix, emphasising the sacred, universal and eternal nature of the empire.

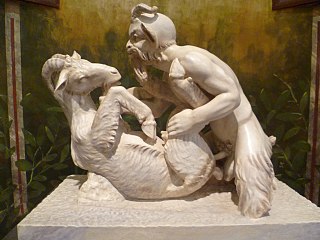

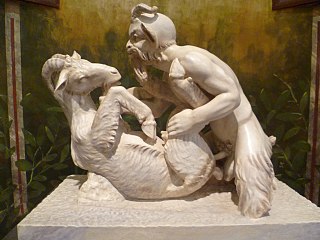

Erotic art in Pompeii and Herculaneum has been both exhibited as art and censored as pornography. The Roman cities around the bay of Naples were destroyed by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD, thereby preserving their buildings and artefacts until extensive archaeological excavations began in the 18th century. These digs revealed the cities to be rich in erotic artefacts such as statues, frescoes, and household items decorated with sexual themes.

Sanchi Stupa is a Buddhist complex, famous for its Great Stupa, on a hilltop at Sanchi Town in Raisen District of the State of Madhya Pradesh, India. It is located, about 23 kilometers from Raisen town, district headquarter and 46 kilometres (29 mi) north-east of Bhopal, capital of Madhya Pradesh.

The Greco-Buddhist art or Gandhara art is the artistic manifestation of Greco-Buddhism, a cultural syncretism between Ancient Greek art and Buddhism. It had mainly evolved in the ancient region of Gandhara, located in the northwestern fringe of the Indian subcontinent.

Bharhut is a village located in the Satna district of Madhya Pradesh, central India. It is known for its famous relics from a Buddhist stupa. What makes Bharhut panels unique is that each panel is explicitly labelled in Brahmi characters mentioning what the panel depicts. The major donor for the Bharhut stupa was King Dhanabhuti.

Venus Anadyomene is one of the iconic representations of the goddess Venus (Aphrodite), made famous in a much-admired painting by Apelles, now lost, but described in Pliny's Natural History, with the anecdote that the great Apelles employed Campaspe, a mistress of Alexander the Great, for his model. According to Athenaeus, the idea of Aphrodite rising from the sea was inspired by the courtesan Phryne, who, during the time of the festivals of the Eleusinia and Poseidonia, often swam nude in the sea. A scallop shell, often found in Venus Anadyomenes, is a symbol of the female vulva.

Gajalakshmi, also spelt as Gajalaxmi, is one of the most significant Ashtalakshmi aspects of the Hindu goddess of prosperity, Lakshmi.

Bhokardan is a metropolis in the Indian state of Maharashtra and is one the oldest cities in India. Bhokardan was a part of the Hyderabad State until it joined India in 1948 as part of the Annexation of Hyderabad. In 1960, it became a part of the newly formed state of Maharashtra from the bilingual Bombay state. The ruins of the old fortifications are still visible around the city; the area of the old fort now houses tehsil offices. Bhokardan has been identified by modern historians as the capital of an ancient district raja Bhogavardhan.

Sculpture in the Indian subcontinent, partly because of the climate of the Indian subcontinent makes the long-term survival of organic materials difficult, essentially consists of sculpture of stone, metal or terracotta. It is clear there was a great deal of painting, and sculpture in wood and ivory, during these periods, but there are only a few survivals. The main Indian religions had all, after hesitant starts, developed the use of religious sculpture by around the start of the Common Era, and the use of stone was becoming increasingly widespread.

A salabhanjika or shalabhanjika is a term found in Indian art and literature with a variety of meanings. In Buddhist art, it means an image of a woman or yakshi next to, often holding, a tree, or a reference to Maya under the sala tree giving birth to Siddhartha (Buddha). In Hindu and Jain art, the meaning is less specific, and it is any statue or statuette, usually female, that breaks the monotony of a plain wall or space and thus enlivens it.

The Indo-Greeks practiced numerous religions during the time they ruled in the northwestern Indian subcontinent from the 2nd century BCE to the beginning of the 1st century CE. In addition to the worship of the Classical pantheon of the Greek deities found on their coins, the Indo-Greeks were involved with local faiths, particularly with Buddhism, but also with Hinduism and Zoroastrianism.

In classical mythology, Cupid is the god of desire, erotic love, attraction and affection. He is often portrayed as the son of the love goddess Venus and the god of war Mars. He is also known as Amor. His Greek counterpart is Eros. Although Eros is generally portrayed as a slender winged youth in Classical Greek art, during the Hellenistic period, he was increasingly portrayed as a chubby boy. During this time, his iconography acquired the bow and arrow that represent his source of power: a person, or even a deity, who is shot by Cupid's arrow is filled with uncontrollable desire. In myths, Cupid is a minor character who serves mostly to set the plot in motion. He is a main character only in the tale of Cupid and Psyche, when wounded by his own weapons, he experiences the ordeal of love. Although other extended stories are not told about him, his tradition is rich in poetic themes and visual scenarios, such as "Love conquers all" and the retaliatory punishment or torture of Cupid.

Hindu art encompasses the artistic traditions and styles culturally connected to Hinduism and have a long history of religious association with Hindu scriptures, rituals and worship.

Vaikuntha-Kamalaja is a composite androgynous form of the Hindu god Vishnu and his consort Lakshmi. Though inspired by the much more popular Ardhanarishvara form of Shiva and Parvati, Vaikuntha-Kamalaja is a rare form, mostly restricted to Nepal and the Kashmir region of India.

Vaikuntha Chaturmurti or Vaikuntha Vishnu is a four-headed aspect of the Hindu god Vishnu, mostly found in Nepal and Kashmir. The icon represents Vishnu as the Supreme Being. He has a human head, a lion head, a boar head and a fierce head. Sometimes, even three-headed but aspects of Vishnu where the fierce rear head is dropped are considered to represent Vaikuntha Chaturmurti. Though iconographical treatises describe him to eight-armed, he is often depicted with four. Generally, Vaikuntha Chaturmurti is shown standing but sometimes he is depicted seated on his vahana (mount) Garuda.

The Art of Mathura refers to a particular school of Indian art, almost entirely surviving in the form of sculpture, starting in the 2nd century BCE, which centered on the city of Mathura, in central northern India, during a period in which Buddhism, Jainism together with Hinduism flourished in India. Mathura "was the first artistic center to produce devotional icons for all the three faiths", and the pre-eminent center of religious artistic expression in India at least until the Gupta period, and was influential throughout the sub-continent.

The Stupa No. 2 at Sanchi, also called Sanchi II, is one of the oldest existing Buddhist stupas in India, and part of the Buddhist complex of Sanchi in Madhya Pradesh. It is of particular interest since it has the earliest known important displays of decorative reliefs in India, probably anterior to the reliefs at the Mahabodhi Temple in Bodh Gaya, or the reliefs of Bharhut. It displays what has been called "the oldest extensive stupa decoration in existence". Stupa II at Sanchi is therefore considered as the birthplace of Jataka illustrations.

The House of the Greek Epigrams is a Roman residence in the ancient town of Pompeii that was destroyed by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE. It is named after wall paintings with inscriptions from Greek epigrams in a small room (y) next to the peristyle.