Anubis, also known as Inpu, Inpw, Jnpw, or Anpu in Ancient Egyptian is the god of funerary rites, protector of graves, and guide to the underworld, in ancient Egyptian religion, usually depicted as a canine or a man with a canine head.

Ancient Egyptian religion was a complex system of polytheistic beliefs and rituals that formed an integral part of ancient Egyptian culture. It centered on the Egyptians' interactions with many deities believed to be present and in control of the world. About 1500 deities are known. Rituals such as prayer and offerings were provided to the gods to gain their favor. Formal religious practice centered on the pharaohs, the rulers of Egypt, believed to possess divine powers by virtue of their positions. They acted as intermediaries between their people and the gods, and were obligated to sustain the gods through rituals and offerings so that they could maintain Ma'at, the order of the cosmos, and repel Isfet, which was chaos. The state dedicated enormous resources to religious rituals and to the construction of temples.

Isis was a major goddess in ancient Egyptian religion whose worship spread throughout the Greco-Roman world. Isis was first mentioned in the Old Kingdom as one of the main characters of the Osiris myth, in which she resurrects her slain brother and husband, the divine king Osiris, and produces and protects his heir, Horus. She was believed to help the dead enter the afterlife as she had helped Osiris, and she was considered the divine mother of the pharaoh, who was likened to Horus. Her maternal aid was invoked in healing spells to benefit ordinary people. Originally, she played a limited role in royal rituals and temple rites, although she was more prominent in funerary practices and magical texts. She was usually portrayed in art as a human woman wearing a throne-like hieroglyph on her head. During the New Kingdom, as she took on traits that originally belonged to Hathor, the preeminent goddess of earlier times, Isis was portrayed wearing Hathor's headdress: a sun disk between the horns of a cow.

Harpocrates was the god of silence, secrets and confidentiality in the Hellenistic religion developed in Ptolemaic Alexandria. Harpocrates was adapted by the Greeks from the Egyptian child god Horus, who represented the newborn sun, rising each day at dawn. Harpocrates's name was a Hellenization of the Egyptian Har-pa-khered or Heru-pa-khered, meaning "Horus the Child". Horus is represented as a naked boy with his finger to his mouth, a realisation of the hieroglyph for "child" (𓀔). Misunderstanding this gesture, the later Greeks and Roman poets made Harpocrates the god of silence and secrecy.

Nephthys or Nebet-Het in ancient Egyptian was a goddess in ancient Egyptian religion. A member of the Great Ennead of Heliopolis in Egyptian mythology, she was a daughter of Nut and Geb. Nephthys was typically paired with her sister Isis in funerary rites because of their role as protectors of the mummy and the god Osiris and as the sister-wife of Set.

Bes, together with his feminine counterpart Beset, is an ancient Egyptian deity worshipped as a protector of households and, in particular, of mothers, children, and childbirth. Bes later came to be regarded as the defender of everything good and the enemy of all that is bad. According to Donald Mackenzie in 1907, Bes may have been a Middle Kingdom import from Nubia or Somalia, and his cult did not become widespread until the beginning of the New Kingdom, but more recently several Bes-like figurines have been found in deposits from the Naqada period of pre-dynastic Egypt, like the thirteen figurines found at Tell el-Farkha

In Egyptian mythology, Wepwawet was originally a deity of funerary rites, war, and royalty association, whose cult centre was Asyut in Upper Egypt. His name means opener of the ways and he is often depicted as a wolf standing at the prow of a solar-boat. Some interpret that Wepwawet was seen as a scout, going out to clear routes for the army to proceed forward. One inscription from the Sinai states that Wepwawet "opens the way" to king Sekhemkhet's victory.

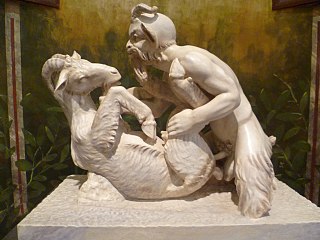

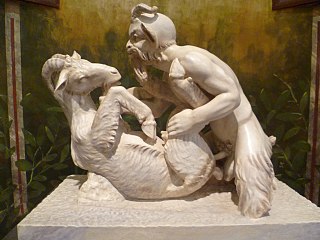

Erotic art in Pompeii and Herculaneum has been both exhibited as art and censored as pornography. The Roman cities around the bay of Naples were destroyed by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD, thereby preserving their buildings and artefacts until extensive archaeological excavations began in the 18th century. These digs revealed the cities to be rich in erotic artefacts such as statues, frescoes, and household items decorated with sexual themes. The ubiquity of such imagery and items indicates that the treatment of sexuality in ancient Rome was more relaxed than in current Western culture. However, much of what might strike modern viewers as erotic imagery, such as oversized phalluses, could arguably be fertility imagery. Depictions of the phallus, for example, could be used in gardens to encourage the production of fertile plants. This clash of cultures led to many erotic artefacts from Pompeii being locked away from the public for nearly 200 years.

The Alexander Mosaic, also known as the Battle of Issus Mosaic, is a Roman floor mosaic originally from the House of the Faun in Pompeii that dates from c. 100 BC.

The National Archaeological Museum of Naples is an important Italian archaeological museum, particularly for ancient Roman remains. Its collection includes works from Greek, Roman and Renaissance times, and especially Roman artifacts from the nearby Pompeii, Stabiae and Herculaneum sites. From 1816 to 1861, it was known as Real Museo Borbonico.

Serapis or Sarapis is a Graeco-Egyptian God. The cult of Serapis was created during the third century BC on the orders of Greek Pharaoh Ptolemy I Soter of the Ptolemaic Kingdom in Egypt as a means to unify the Greeks and Egyptians in his realm.

The Pompeian Styles are four periods which are distinguished in ancient Roman mural painting. They were originally delineated and described by the German archaeologist August Mau (1840–1909) from the excavation of wall paintings at Pompeii, which is one of the largest groups of surviving Roman frescoes.

Hellenistic art is the art of the Hellenistic period generally taken to begin with the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE and end with the conquest of the Greek world by the Romans, a process well underway by 146 BCE, when the Greek mainland was taken, and essentially ending in 30 BCE with the conquest of Ptolemaic Egypt following the Battle of Actium. A number of the best-known works of Greek sculpture belong to this period, including Laocoön and His Sons, Venus de Milo, and the Winged Victory of Samothrace. It follows the period of Classical Greek art, while the succeeding Greco-Roman art was very largely a continuation of Hellenistic trends.

The traditional Berber religion is the ancient and native set of beliefs and deities adhered to by the Berbers. Many ancient Berber beliefs were developed locally, whereas others were influenced over time through contact with others like ancient Egyptian religion, or borrowed during antiquity from the Punic religion, Ancient Canaanite religion, Iberian mythology, and the Ancient Greek religion and Ancient Roman religion and many other world religions that were present with the Berbers. Some of the ancient Berber beliefs still exist today subtly within the Berber popular culture and tradition. Syncretic influences from the traditional Berber religion can also be found in certain other faiths.

The House of the Faun, constructed in the 2nd century BC during the Samnite period, was a grand Hellenistic palace that was framed by peristyle in Pompeii, Italy. The historical significance in this impressive estate is found in the many great pieces of art that were well preserved from the ash of the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD. It is one of the most luxurious aristocratic houses from the Roman Republic, and reflects this period better than most archaeological evidence found even in Rome itself.

The Palestrina Mosaic or Nile mosaic of Palestrina is a late Hellenistic floor mosaic depicting the Nile in its passage from the Blue Nile to the Mediterranean. The mosaic was part of a Classical sanctuary-grotto in Palestrina, a town east of Ancient Rome, in central Italy. It has a width of 5.85 metres and a height of 4.31 metres and provides a glimpse into the Roman fascination with ancient Egyptian exoticism in the 1st century BC, both as an early manifestation of the role of Egypt in the Roman imagination and an example of the genre of "Nilotic landscape", with a long iconographic history in Egypt and the Aegean.

The Temple of Isis is a Roman temple dedicated to the Egyptian goddess Isis. This small and almost intact temple was one of the first discoveries during the excavation of Pompeii in 1764. Its role as a Hellenized Egyptian temple in a Roman colony was fully confirmed with an inscription detailed by Francisco la Vega on July 20, 1765. Original paintings and sculptures can be seen at the Museo Archaeologico in Naples; the site itself remains on the Via del Tempio di Iside. In the aftermath of the temple's discovery many well-known artists and illustrators swarmed to the site.

A Roman mosaic is a mosaic made during the Roman period, throughout the Roman Republic and later Empire. Mosaics were used in a variety of private and public buildings, on both floors and walls, though they competed with cheaper frescos for the latter. They were highly influenced by earlier and contemporary Hellenistic Greek mosaics, and often included famous figures from history and mythology, such as Alexander the Great in the Alexander Mosaic.

The House of the Centenary was the house of a wealthy resident of Pompeii, preserved by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD. The house was discovered in 1879, and was given its modern name to mark the 18th centenary of the disaster. Built in the mid-2nd century BC, it is among the largest houses in the city, with private baths, a nymphaeum, a fish pond (piscina), and two atria. The Centenary underwent a remodeling around 15 AD, at which time the bath complex and swimming pool were added. In the last years before the eruption, several rooms had been extensively redecorated with a number of paintings.

Roman Republican art is the artistic production that took place in Roman territory during the period of the Republic, conventionally from 509 BC to 27 BC.